CUNY’s legacy, the limits and violence of Asian American success stories, and what’s at stake in the fight for accessible public education

June 15, 2018

“First generation American”: This term was used recently to characterize a commencement speech I delivered to my peers in the graduating class of the City University of New York’s Graduate Center. The term is seductive and I identified with it when I was a student in the public schools on Long Island, where my immigrant family and I adjusted to suburban life by describing our town as a “good” neighborhood with “good” schools. Homework was often a compulsory but convenient way for me to avoid thinking about the hierarchies forged and the social bonds secured during and after class. My family’s minority status as low-income Chinese Americans in a white town left me clinging desperately to a fantasy of heroic individualism, what some might call the American Dream. It wasn’t until I arrived to Hunter College, a four-year public college that is a part of the City University of New York (CUNY), that I began learning—through CUNY’s institutional history, curriculum, and heterogeneous student body—that the exceptional image of the successful immigrant obscures this fact: there are populations who have been in this country for centuries and yet continue to be denied the rights to life, care, and well-being.

The term “first generation American” ushers forth, admittedly, an initial sense of pride followed by a great deal of ambivalence. My ambivalence stems from “first generation,” which reminds me of how mobile technological devices, like iPods and later iPhones, are marketed to consumers. Perhaps it’s not entirely strange to see the shared language of “first generation” American success stories and technological devices: the phrase insists on newness and advancement. The model minority tropes that are often associated with Asian Americans are narrative devices that insist on the emergence of a markedly “improved” citizenry. These narrative devices obscure the histories and ongoing forms of exclusion, racial segregation, and dispossession that unsettle any claims to a utopian American identity.

In The Color of Success (2014), Ellen Wu defines a model minority as “a racial group distinct from the white majority, but lauded as well assimilated, upwardly mobile, politically nonthreatening, and definitively not-black.” Invented in the mid-1960s, the narrative tropes associated with the model minority stereotype haven’t vanished. They continue to be reconfigured through dominant representations of Asian American communities who are, or desire to be, upwardly mobile through the “meritocratic” engine of education. The color-line around admissions to elite education is redrawn through high-profile Asian American grievances that a more diverse and inclusive university (one that aims to be reflective of the black and brown populations in the US) produces a racial bias against Asian American students. Just last week, East Asian American communities in New York rallied against Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plans to eradicate a standardized test that has historically barred black and Latinx students’ entry into the city’s specialized public high schools. These protests recall media coverage around Asian Americans who oppose affirmative action. Earlier this year, in an ongoing lawsuit that was filed against Harvard in 2014, legal strategists for a group of Asian Americans demanded that the Ivy League school release admissions materials, claiming that those documents would reveal discrimination against Asian American applicants. Those same legal strategists are affiliated with the case of Abigail Fisher, the white woman who was the face of anti-affirmative action efforts that made their way to the Supreme Court. This coverage reminds us of how defenses for “meritocratic” or “neutral” academic admissions often prop up white supremacy.

The language of “neutral” admissions flattens the racist, specifically anti-black, dimensions of education in the US. The intersection of the racial caste system with the American university speaks to the fact that social exclusion is at the heart of privatizing mobility and communal experience that should be accessible to all. To return to my analogy of mobile technological devices and tropes around narratives of Asian American success: both reflect larger trends of privatizing public infrastructure. Instead of waiting for a public train or a bus and ride with others, you can hail a private car from your phone. Access to elite institutions can seem all the more enticing and necessary if public education is impoverished and dismantled. Social gatekeeping of power is fortified through privatization.

Narrative tropes of the Asian American model minority—of assimilated others, heroic first generation immigrants—are insidious because they accept anti-black violence. Model minority tropes reflect real desires for a limited social mobility that genuflects to the discriminatory attitudes woven into the fabric of everyday life in the US. We live in a society that positions minorities to carry out violence against black and brown life in the US. Asian Americans cannot claim innocence; if we do, then we are not acknowledging the ways that we participate in and uphold white supremacy. Put differently, in the same year that a group of Asian Americans filed their lawsuit against Harvard, NYPD officer Peter Liang killed 28-year old Akai Gurley in a Brooklyn housing project. The lawsuit and the killing are linked: with both, Asian Americans actively barred and deprived black Americans’ access to live fully.

Like smartphones and social media, narrative tropes around the model minority reveal which social experiences are designed to flourish and which are foreclosed. Attention to how model minority tropes are employed can offer up new avenues for reexamining how we might create and occupy inclusive, accessible public spaces in the physical and digital world. We might think about how deep investment in accessible public infrastructure can reorient individual desires for upward mobility towards social movements that value human life—movements that strive to reduce the violence historically and presently inflicted upon indigenous, black, and brown lives in the US and beyond.

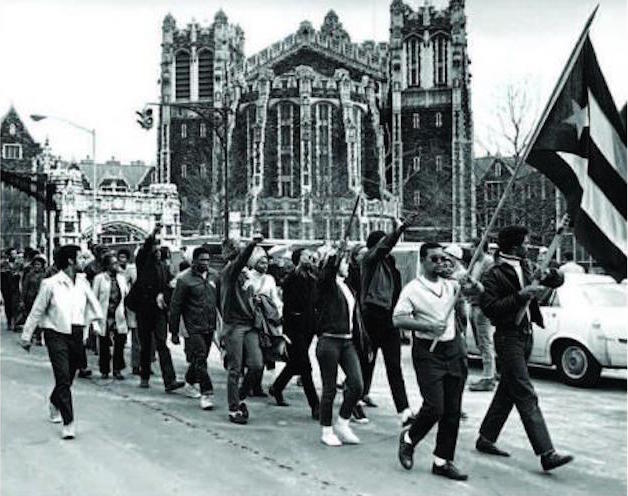

I was an undergraduate, graduate, and teacher at a public university system that spans twenty-four campuses across New York City. CUNY, where I’ve spent over a decade, offers up a history that speaks to ongoing struggles to decolonize education in the US and make public education reflective of all people who live in this country. CUNY’s history of Open Admissions and current student-, labor-, and community-led movements—from antiwar protests to the struggles for ethnic studies programs—gesture towards a desire for a public that enriches lives that are different but not separate from one another.

* * *

The following is Kristina Huang’s CUNY Graduate Center Commencement address, delivered on May 30

Congratulations to the class of 2018 and to our loved ones who gather here today to celebrate our achievements as a community. It is an honor and privilege to be here.

My fellow graduates: We learned from stellar advisors and mentors. In working with each other, we created spaces and events that sustained conversations born from our seminar discussions. Above all, our education at The Graduate Center grounded our studies in the realities and vitality of public education. We became teacher-scholars.

Because so many of us taught while we pursued our doctoral studies, our work at The Graduate Center dialogued with the education of CUNY’s undergraduate student body. I want to highlight our doctoral studies’ relationship to working-class people of color at CUNY and, more specifically, connect our work to what poet-activist-teacher June Jordan called “the symbol, and the fact, of City College.”

I am from the composite undergraduate student body that makes up CUNY. Many are from families who are relatively new to this country. Many are from families who have been here for centuries yet continue to confront inequality and forms of un-freedom in a world that privileges profit over human life. “I can’t breathe” articulates the challenges set before us. You and I are learning to raise ourselves up in these times, and the history of CUNY reminds us: There is power in people transforming themselves in the face of violence and erasure.

Let me begin with my understanding of the promise of CUNY as an organic relationship: I was a lecturer at the same time and campus where one of my sisters was an undergraduate. We were at City College, where in 1969 Black and Puerto Rican students demanded that the college be a reflection of New York City’s public schools. My younger sister saw me try to balance teaching with my doctoral studies. I saw her square work with school. Some of her friends were students in my classroom. At the same time, we read The Black Jacobins and heard from our peers about Palestinian struggles. Later on, I taught at Queens College, where my other younger sister attended as an undergraduate.

I am the first in my family to acquire a B.A. but I am hardly the first to struggle with the language and habits of an unfamiliar place. My mother immigrated, for instance, when she was eighteen and made Manhattan’s Chinatown her first home in the US. At eighteen I attended CUNY’S Hunter College, which was originally a women’s college for training teachers. I was naïve then to think that I was the first in my family to pursue a B.A.; I learned that one of my uncles briefly attended City College in the 80s. I didn’t know then that members of my family had been or would become students on the sister campuses of CUNY. Through my family and time teaching at City College, I learned that CUNY’s foundational promise to be free was not just a matter of money but also a commitment to communal wealth. To be free, to be liberated, stems from mutual recognition of our differences as we independently struggle to lift ourselves from the conditions that bind us.

My fellow graduates: We benefited from and contributed to CUNY’s promise and power. Our Ph.D.s are part of this institution that spans five city boroughs, which are also homes to various communities who raise themselves on their own terms. Their lives are linked with our academic milestones. This is remarkable, and we must remain committed to that organic relationship. Through our teaching and learning with this city’s communities, we have dialogued with the hopes and desires of the people whom CUNY serves. This is our fortune and our reason to celebrate tonight and every day.

Rather than rehearse the familiar stories associated with the state of public higher education—all of which reflect the domestic and global wars waged against people and the environment we live in—I’ll conclude with an image that symbolizes the power in people behind CUNY.

The image: a red door, painted on it a black fist gripping a pencil. Many times I passed this door in the North Academic building at City College, usually running from my own coursework, or eagerly walking to meet my sister for a coffee break. The door was the entrance to the Morales/ Shakur Student and Community Center. Named after two revolutionaries—the former fought for Puerto Rican independence, the latter fought for Black liberation—the center was created in 1989 by an occupation of students and community members fighting against tuition hikes. The space became a center for organizing, “know-your-rights” training, student advising, and it provided food and babysitting services to the communities surrounding the campus. That space was removed and replaced in 2013 with a Careers Center.

Years ago, I rushed past that door. I did not recognize that the Morales/Shakur Center was built on this conviction: We are learning to raise ourselves by writing our independence and future. But I am realizing that this image of the door has lodged itself in me. I share this image with you today because the ability to make a living, to have access to care, and to enjoy the right to well-being are indeed under attack. For many, our current political moment is a rude awakening; for many, these struggles have been long-standing.

When I taught a class at the College of Staten Island, only a handful of students knew that Eric Garner was murdered in their borough. Even our physical proximity to the struggles of others does not necessarily mean we will or are willing to recognize them. Unfinished, difficult work is here and ahead.

I was physically closer to the Morales/Shakur Center’s door years ago, but I am opening to this fact: that door at City College represented a defiant commitment to enacting change. To my mind the door now figures as the dream in concrete social transformation. As people who serve the people, we will, I hope, raise ourselves with the dreams enacted at CUNY—to resist private comfort and individual profit from these dreams, and to commit ourselves to the people we’ve encountered at CUNY, students and staff. The red door with the black fist calls for action that will write our future. It calls us to dream boldly through our demands and to materialize a world where we can all breathe independently together.

Thank you, fellow graduates, and to the people behind CUNY, those who patiently, anonymously, generously worked to insist that our shared education be accessible and collective liberation be possible. Good luck to us all.