An introduction to the present-day protests

January 13, 2021

Editors’ Note: Today, we kick-off a new series on The Margins: Syllabus. The syllabus is another way to tell a story. It can give us the tools to build a new understanding of an idea or event or concept. But the story that the syllabus tells is unfinished, written to be wrestled with, poked and prodded, held at length, and completed in conversation with oneself and others. Taking the form of a carefully organized and annotated list of books, articles, visual art, and other work found in print or online, each of our Syllabi will call on our readers to deepen their understanding of an issue or topic related to Asian or Asian diasporic literature, history, or social movements. We hope for the Syllabus series to extend far outside of the formal classroom and into living rooms, zoom rooms, and of course the streets. In this first installment, we read about dreaming of democracy in Thailand.

Since July 2020, people have taken to the streets in protest in Thailand in numbers unprecedented for over a decade and with expansive demands unseen for close to half a century. At a minimum, they are calling for Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha to dissolve parliament and resign, new free and fair elections to be held, a new constitution to be drafted, an end to state persecution of dissidents, and reform of the institution of the monarchy. Marked by the juxtaposition of playful symbols (including singing hamsters and plastic rubber ducks) with stinging critique of the collusion between the monarchy and the military, the protests aim to make the 88-year-old promise of the end of the absolute monarchy real while creating a new society informed by radical equality and recognition of difference.

On June 24, 1932, a civilian-military coalition called the People’s Party fomented a transformation in Thailand from absolute to constitutional monarchy that aimed to bring the king under the law. Since then, the rulers and the ruled have been engaged in a struggle over who should hold power and who should be able to participate in politics. Twelve ‘successful’ (meaning that power was seized) military coups, at least seven attempted coups, and 20 constitutions are evidence of this struggle. Further, while the then-reigning king, Rama 7, abdicated in 1935 and the monarchy initially faded from public life, the royalist desire by some members of the polity for an absolutist regime did not. With extensive U.S. anti-communist counterinsurgency aid beginning in the 1950s, a monarchy-military alliance formed that ensured that more often than not, the rulers came out on top of the ruled in the ongoing struggle that defines the Thai polity. Dissidents have borne the cost for daring to challenge unjust power through censorship, imprisonment, extrajudicial killing, disappearance, and massacres.

The kings who have reigned during this period—Rama 9, who became king in 1946 following the unexpected death of his older brother and ruled until his own death in October 2016, and Rama 10, his son and the current king—and the institution of the monarchy, which controls significant financial, property and bureaucratic holdings, are unavoidably central figures in both the polity and the conflicts within it. They are neither under the law nor above politics. Article 112 of the Criminal Code, which defines the crime of lèse majesté and stipulates the harsh punishment of three-to-fifteen years imprisonment for each count, means that asking sharp questions about the monarchy also means risking one’s liberty.

What is unfolding on the streets of Bangkok, Chiang Mai, Khon Kaen, and many other provincial cities in Thailand since late 2020 is the making real of democracy that dissidents have been dreaming up and working towards since 1932. In doing so, activists are encountering the same risks and dangers, including those of the cold metal bars of prison, the possibility of exile, and the threat of being killed by a regime that does not comprehend the irrefutable dignity of their lives. What follows below is a series of readings and virtual exhibitions to frame the present-day struggle and its significance. The sources are divided into five categories, each named by an action: recording repression, engaging in dissent, creating archives against domination, tracing the unspeakable, and imagining the future. Teaching, and learning, struggle is an active, ongoing process. This is a syllabus for a class in dreaming democracy intended to be attuned to the streets of protest rather than the university classroom.

I. Recording Repression

What forms does violence take, and what forms and structures hold it up? What is remembered and what is left in an uneasy state of unremembering? What kinds of documentation and representation challenge violence and begin to imagine accountability? What do repression and justice sound, look, and feel like?

1) Katherine Bowie. Rituals of National Loyalty: An Anthropology of the State and Village Scout Movement in Thailand. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

In October 1973, people filled the streets to call for a constitution in Thailand and an end to 15 years of dictatorship. They were successful and three years of democracy began in which students protested, farmers worked for land reform, workers carried out strikes, and dissident culture flourished. But transitions to communism in neighboring countries made the powerful nervous and a right-wing backlash began. On October 6, 1976, this culminated in a massacre at Thammasat University and a military coup. Central to this were the Village Scouts, a citizen group who transgressed the line between civil society and the para-state to foment hatred and violence. In Rituals of National Loyalty, Katherine Bowie traces their formation with the support of the Border Patrol Police, a CIA-trained paramilitary force. Her analysis of a multi-day initiation into the group illustrates how intimacy and power intertwined to bind members to the monarchy they promised to protect.

2) Thongchai Winichakul. Moments Of Silence: The Unforgetting of the October 6, 1976, Massacre in Bangkok. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2020.

Thongchai Winichakul was a student leader present at Thammasat University on the morning of the massacre. State and para-state forces attacked, shot, and lynched the students who were massed inside the university. According to the government, 46 people were killed, 180 were injured, and 3,059 were arrested, although the unofficial estimates were higher. Thongchai survived the massacre but was then imprisoned for nearly two years on a series of trumped-up charges with 17 other activists. In the years since, the impunity of the perpetrators has remained intact and the massacre and coup justified as necessary to protect the monarchy and prevent communism. In Moments of Silence, Thongchai weaves together memoir and history to examine how the massacre is at once unremembered and unforgotten. Though the book cannot resolve the devastating violence of the past, its irresolution calls into question every subsequent instance of violence that remain similarly unresolved and cloaked in impunity.

3) Luke Duggleby and Protection International. For Those Who Died Trying.

Ongoing photo project and exhibit, multiple locations and online at Maiiam Contemporary Art Museum. Short film on the project available here.

An estimated at least 200 human rights defenders have been assassinated or disappeared in Thailand since the 1950s. Challenging power—whether that of capital, the military, the police, or otherwise—is dangerous and securing accountability difficult. In For Those Who Died Trying, Luke Duggleby challenges impunity by citing and remembering violence. Working with Protection International, an NGO that works on behalf of human rights defenders, he photographs the photographs kept by families in the places where their loved ones were assassinated or disappeared. Three-dimensional landscapes of streets, sidewalks, parking lots, and forests are interrupted by two-dimensional photographs of those who were once present. Inspired by the photo project, Frank Horvat created a series of string quartet pieces based on the names of those killed. Like the photographs, the music unsettles rather than soothes. The project remains ongoing because the killings are ongoing.

4) People’s Information Center on the April-May 2010 Crackdown (PIC). Truth for Justice: A Fact-finding Report on the April-May 2010 Crackdowns in Thailand. Bangkok: PIC, 2017. [English translation and summary of ศูนย์ข้อมูลประชาชนผู้ได้รับผลกระทบจากการสลายการชุมนุมกรณี เม.ย.-พ.ค. 53 (ศปช.). ความจริงเพื่อความยุติธรรม: เหตุการณ์และผลกระทบจากการสลายการชุมนุม เมษา-พฤษภา 53. กรุงเทพฯ: ศปช., 2555 [2012].]

Between the September 2006 and May 2014 coups, Thai politics were divided into the two poles of royalist-nationalist yellow shirts, who supported the coups, and populist-nationalist red shirts who opposed them. In March 2010, several hundred thousand red shirt protestors launched an extended protest in Bangkok calling for the dissolution of the appointed government of Abhisit Vejjajiva and elections. Rather than entering into dialogue, Abhisit’s government ordered their removal from the city. Between April 10 and May 19, at least 94 people were killed and over 2,000 injured in the military crackdown. Of the five reports commissioned in the aftermath, that of the People’s Information Center, a coalition of civil society activists, was the most detailed and rigorous, and the only independent report. The original 1,300+ page Thai-language report was condensed and translated into English and is available as a free PDF.

5) Benjamin Tausig. Bangkok is Ringing: Sound, Protest, and Constraint. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

While the PIC Report tells the story of the protests through the violence with which they ended, Benjamin Tausig instead assembles a constellation of reflections on the protests through the lens of sound, including the rich songs of struggle that could be heard from the protest stage and in the occupation encampment late into every evening. Much of the sound is unmelodic: the government propaganda broadcasts and the threat that the military will use the LRAD (Long Range Acoustic Device) to terrorize and silence the protestors. The star of Bangkok is Ringing is Mii, a red-shirt protestor and phin (stringed instrument) performer. Mii teaches Tausig how to play the phin, and Tausig’s account of their exchange illustrates the possibilities of both teaching and dissent. An audio version of the book, which combines the text of the chapters with sound recorded during the protests is available.

II. Engaging in Dissent

Like repression, dissent is constant. What voices and ideas animate opposition to injustice? What unexpected strategies and languages arise from state attempts to suppress speech? And, what is the gender of dissent?

1) Pridi Banomyong. Pridi by Pridi: Selected Writings on Life, Politics and Economy. Translated by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2000.

Pridi Banomyong was a jurist, the civilian leader of the People’s Party that fomented the transformation from absolute to constitutional monarchy in 1932, and the founder of Thammasat University, the country’s first open university. In 1933, he developed an Outline Economic Plan (OEP) to redistribute resources and place their governance with the people, not the lords or the state. Almost from the very beginning, Pridi was accused of being too radical, at turns a communist and a republican. He went into exile first in 1933 following the announcement of the OEP and then permanently following the death of Rama 8 in 1946. This collection contains key documents of the People’s Party, including the first constitutional charter, the OEP, as well as Pridi’s writings on democracy and dictatorship. Pridi’s commitment to the people continues to inspire activists today, who frequently place themselves in a genealogy that begins with him.

2) Kasian Tejapira. Commodifying Marxism: The Formation of Modern Thai Radical Culture, 1929-1958. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press, 2001.

The Communist Party of Thailand (CPT) was officially founded on December 1, 1942, and the party declared an armed struggle against the Thai state on August 7, 1965. But long before the first shots were fired and even over a decade before the party was founded, Chinese, Vietnamese, and Thai socialists, communists, and leftists of other stripes were organizing and exchanging ideas. Newspapers, journals, and publishing houses proliferated, sometimes with unexpected capitalist patrons. What is most striking is that the radical culture that Kasian outlines in Commodifying Marxism is one of tremendous possibility, of another Thai society and another world. In those early years, the imagination and solidarity necessary to conjure it into existence had not been forced into hiding through the unrelenting threat of prison and military violence. In late 2020, it feels as though such possibility may be returning.

3) Sunisa Manning. A Good True Thai. Singapore: Epigram Books, 2020.

Sunisa Manning’s novel unravels the upheaval of the 1973-1976 period through the lives and deaths, joys and sorrows, of three young people from different class and ethnic backgrounds. Det, the only son of a government minister father and a mother with royal title; Chang, the only son of a factory worker who lives in a slum; and Lek, the oldest child in a Chinese immigrant family, all meet in the halls of Chulalongkorn University, the country’s elite university that began as a school for royal pages. Their unlikely friendship is matched by the boundaries they transgress as they first become labor organizers and then join the CPT in the jungle. Long before the CPT ultimately disintegrates in the mid-1980s, the lives of the three are turned upside down. A Good True Thai powerfully unsettles what is imagined to be stable, about identity, loyalty, and the promise of struggle.

4) Kanokrat Lertchoosakul. The Rise of the Octobrists: Power and Conflict Among Former Left-Wing Student Activists in Contemporary Thai Politics. New Haven: Yale University Center for Southeast Asian Studies, 2016.

The Octobrists | คนเดือนตุลา is the name given to those who were student activists between October 1973 and October 1976. Many remain significant figures in the political, intellectual, cultural, and business worlds, such as Thongchai Winichakul and Kasian Tejapira, whose works are included above. In The Rise of the Octobrists, Kanokrat asks how and why these once-united progressive, radical, even revolutionary students broke with one another and took up a series of political positions contra to their original stances. At their most extreme, some Octobrists have become defenders of the monarchy and advocates of coups. Through oral history interviews and sharp analysis, these fractures are given a rich, human face. Kanokrat’s message is that politics are messy, painful, and fraught with the peril of betrayal, even when the best intentions for justice and social transformation seem to be in the hearts of the actors.

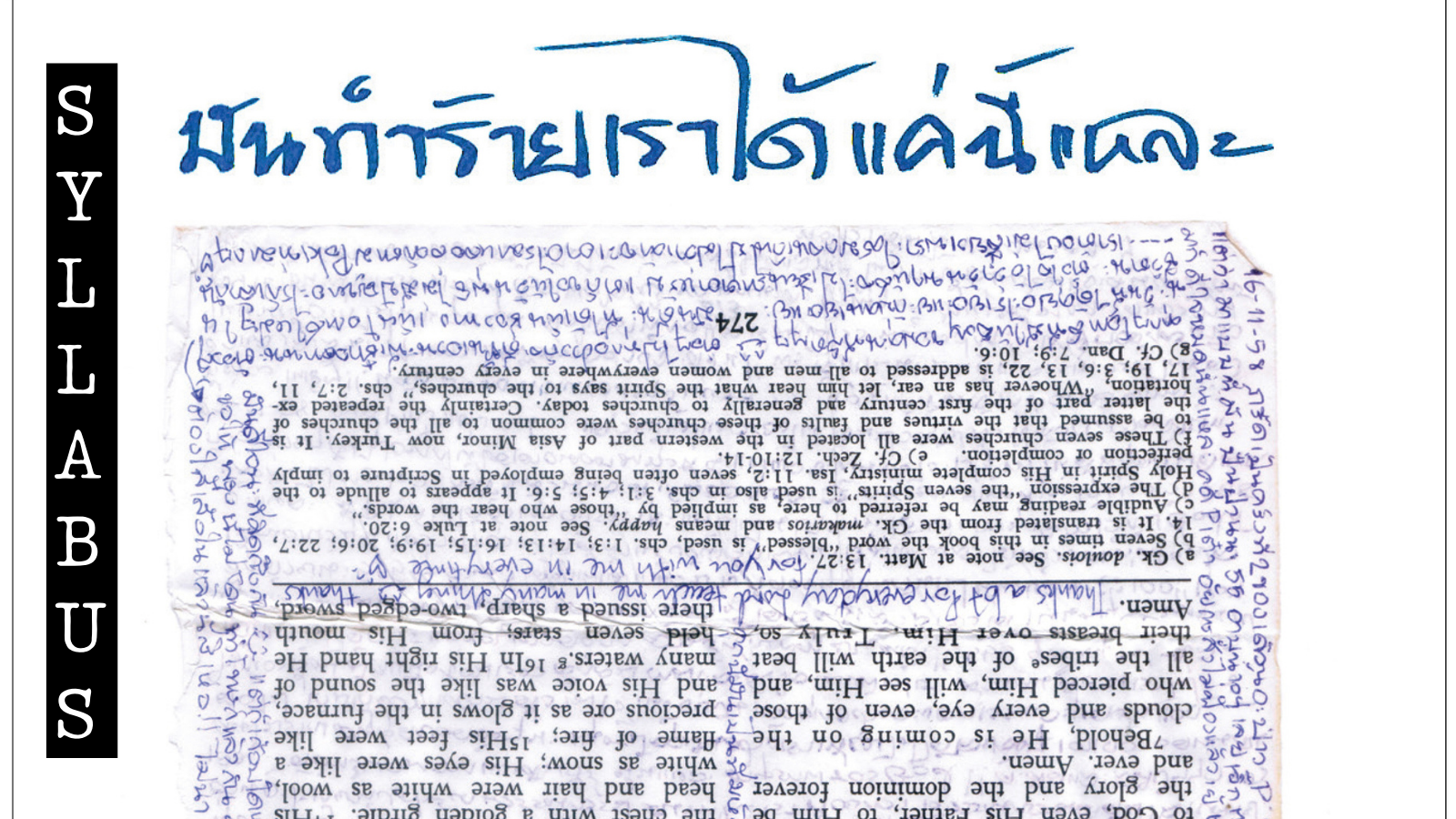

5) Prontip Mankhong. “All They Could Do To Us (An Excerpt).” Translated by Tyrell Haberkorn. The Margins, Asian American Writers Workshop. February 12, 2020.

Shortly after the May 22, 2014 coup, Prontip Mankhong and Patiwat Saraiyaem were arrested and imprisoned for over two years for lèse majesté for their participation in a play, “The Wolf Bride,” deemed to insult Rama 9. All They Could Do To Us | มันทำร้ายเราได้แค่นี้แหละ is Prontip’s memoir of her 744 days imprisoned in the Central Women’s Prison in Bangkok. Across the 852 pages published by Aan Press, a daring progressive literary publisher in Thailand, she details her daily life behind bars, the intimate and difficult intersections of her life with those of the many women she meets, the special surveillance and suppression she faces as a political prisoner, and the unexpected joy she finds behind the bars. At once a guide to surviving prison life, the book is also a guide for everyone trying to find liberation in a society under military rule.

III. Creating Archives Against Domination

The National Archive of Thailand, located on Samsen Road in Bangkok, is the official repository of what the state chooses for the people to remember. But memory does not belong to the state alone. What do the people decide to document and remember, and how do they challenge the dominant narrative presented by the state?

1) โครงการบันทึก 6 ตุลา/Documentation of October 6. https://doct6.com/

Under Thailand’s Official Information Act, state agencies are supposed to send their materials to the National Archives on a regular basis. But there are exceptions: materials related to the monarchy are to be held for seventy-five years and those related to the national university for 20 years before release. If this is not long enough, then the materials may be held back indefinitely in five-year increments. In addition, none of the state security or military units send any documents to the National Archives. Countering this lacunae, the Documentation of October 6 online archive, founded by victims, academics, and activists in 2017, is a collection of archival materials, court documents, state records, and newspaper clippings, as well as video interviews with survivors and families of those who who were killed and academic and other commentary pieces.

2) ไอลอว์. ศูนย์ข้อมูลกฎหมายและคดีเสรีภาพ. http://freedom.ilaw.or.th | iLaw.

Freedom of Expression Documentation Center. https://freedom.ilaw.or.th/en

iLaw, or the Internet Law Reform Dialogue, works to increase access to justice by providing clear, concise information about how to exercise one’s rights in Thailand. During the 2020 protests, iLaw led a campaign to urge parliament to consider a constitution drafted by the people, which was summarily dismissed. The online, bilingual Freedom of Expression Documentation Center, contains detailed information on hundreds of cases related to political expression and freedom of expression, including lèse majesté (Article 112), sedition (Article 116), Computer Crimes Act, Public Assembly Act, and more. For each case in the online documentation center, iLaw includes the name of the accused, the alleged crimes, any decisions made, and details about location and time of court hearings so that observers may attend. This is an archive of both the daring to dissent and the varieties of legal repression with which it is met. Between October and December 2020, new cases have been added on an almost daily basis as the government uses the courts to try to silence opposition.

3) โครงการจัดเก็บเอกสารของกลุ่มคนหลากหลายทางเพศในประเทศไทย/Thai Rainbow Archive. http://thairainbowarchive.anu.edu.au/

The Thai Rainbow Archive was a joint project of the Australian National University and Thai LGBTQIA+ organizations to collect and make publicly accessible rare queer periodicals. Thirty-three different publications from the 1980s-2000s were collected and digitized in full, including newsletters of community and activist organizations as well as commercial publications. While the vast majority of the materials are those produced by and geared towards gay men and transgender communities, both publications of Thailand’s first lesbian organization, Anjaree | อัญจารี, are included as well. Anjaree San | อัญจารีสาร (1994-1999) and Chotmai Khao Anjaree | จดหมายข่าวอัญจารี (2000-2001) contain rich documentation of lesbian organizing, and also of the lives of women who loved women throughout the country. Women wrote in with accounts of discrimination, but also of the urgency of finding love and one another.

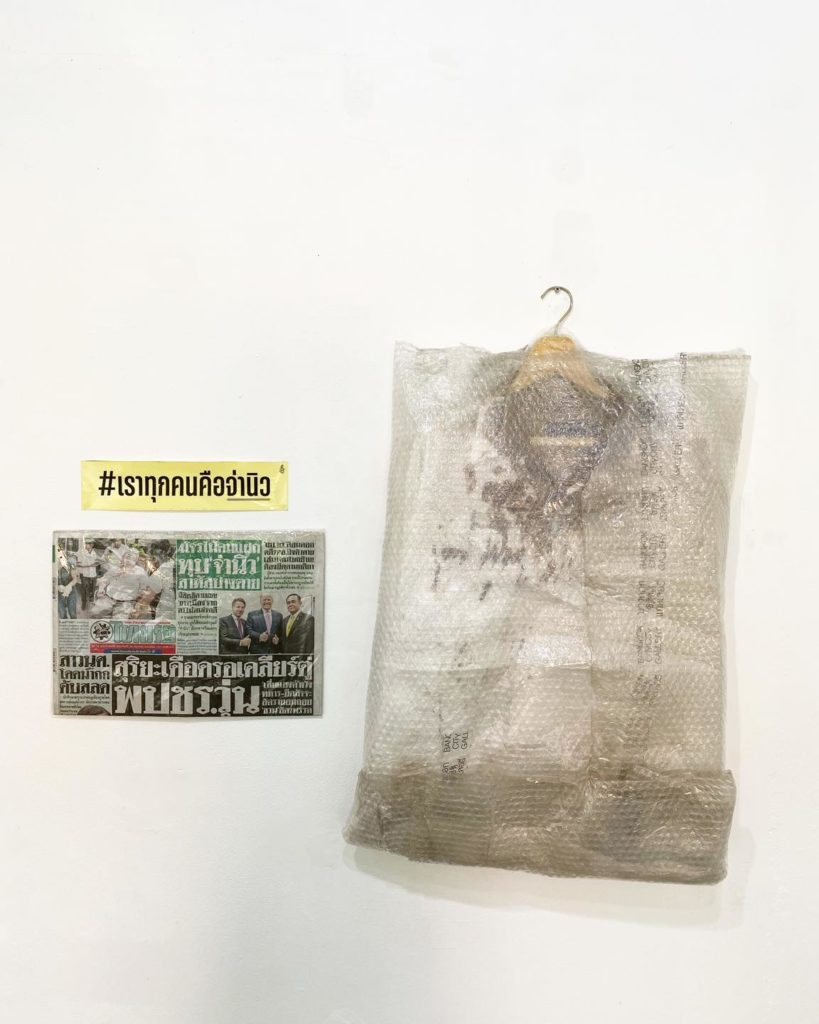

4) พิพิธภัณฑ์สามัญชน/Museum of the Commoners. https://commonmuze.com/ and https://www.facebook.com/commonmuze/

The Museum of the Commoners is a series of online and offline exhibits about people’s lives and struggle in Thailand. Anon Chawalawan, the founder, explains that while Thailand, like every country, has a museum that tells the story of the glory of the nation, the stories of the common people are missing. Beginning in 2018, he began collecting t-shirts, fliers, signs, banners, books, newsletters, ephemeral protest items, letters to and from political prisoners, and other materials that record and tell the story of the people’s hardship, struggles, and aspects of their lives that would otherwise be forgotten. Between October and December 2020, an exhibit of the museum’s holdings, “COLLECTED: unwritten history,” accompanied by a series of workshops, was held at Many Cuts Art Space in Chachoengsao province. The museum works to collect people’s history, and in so doing, change what counts as history.

IV. Tracing the Unspeakable

Although Article 112 stipulating the crime of lèse majesté has been present in the Thai Criminal Code since its last revision in 1957, it was rarely invoked, until the September 19, 2006 coup. Cases steadily rose until the May 22, 2014 coup, after which the number of convictions skyrocketed. People were prosecuted for performing in plays, such as Prontip Mankhong mentioned above, as well as for conversations in taxis, bathroom graffiti, and Facebook posts. The longest sentence was meted out to a man named Wichai, sentenced to 35 years for seven posts. The goal of the law has become to silence all expression that departs from uncritical praise of the institution or individual royal figures. If readers explore iLaw’s Freedom of Expression Documentation Center, a trajectory of this silencing is visible. Yet there is another trajectory to be traced: despite the possibility of punishment, people have always spoken out. How have these voices spoken the unspeakable, and what have they sacrificed to do so?

1) Somsamai Srisudravarna [Jit Phumisak]. 1987. “The Real Face of Thai Saktina Today.” Translated by Craig Reynolds. In Thai Radical Discourse: The Real Face of Thai Feudalism Today. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program Publications. Pages 43-148. [English translation of สมสมัย ศรีศูหรพรรณ, โฉมหน้าศักดินาไทย (สำนักพิมพ์ศรีปัญญา, ๒๕๔๘)].

Jit Phumisak was one of the most important Thai Marxian thinkers of the 20th century. “The Real Face of Thai Saktina Today,” translated painstakingly and playfully by Craig Reynolds, was first published in Thai in 1957 while Jit was a student at Chulalongkorn University. Jit unpacks how the remnants of feudalism impacted Thai society despite the 1932 transformation. The book was quickly banned and Jit was arrested and imprisoned for six years. Upon release, he joined the CPT but was assassinated at age 35 on May 5, 1966 under conditions which remain unclear. His life, work, and death have served as inspiration for generations of student activists, including those in the streets today. When they chant “Down with feudalism, Long live the people” (“ศักดินาจงพินาศ ประชาราษฎร์จงเจริญ), like Jit, they are calling upon the explanatory framework of feudalism to condemn lingering absolutism in the present.

2) คำพิพากษา. คดีดำหมายที่ อ. 3959/2551. คดีแดงหมายที่ อ. 2812/2552. ระหว่างอัยการสูงสุดและนางสาวดารณี ชาญเชิงศิลปกุล. 28 สิงหาคม 2552. [ ฉบับภาษาไทยตีพิมพ์ใน ฟ้าเดียวกัน, ปีที่ 7 ฉบับที่ 3, กรกฎาคม-กันยายน 2552, หน้า 200-231] | Judgment. Black Case No. O.3959/2551. Red Case No. O.2812/2552. Office of the Attorney General versus Daranee Charnchoengsilpakul. 28 August 2009. [English translation published in Fa Diew Kan, 7.4 (October-December 2009), pages 131-151].

One of the early Article 112 prosecutions was of Daranee Charnchoengsilpakul, a journalist and red-shirt speaker. She was accused of lèse majesté related to 55 minutes of speeches she made during political rallies in July 2008. She pled not guilty and on August 29, 2009 Daranee was sentenced to 18 years in prison, or roughly one year for every three minutes of speech. Her sentence was reduced to 15 years on appeal and she was pardoned in August 2016. Few choose to plead innocent because innocent verdicts are rare and a guilty plea results in a halving of one’s sentence. The decision in her case was published in both Thai and English translation and is a rare document of both dissent and the court’s refusal to accept it. Daranee died of metastatic breast cancer at age 62 in May 2020, before the protests began in earnest.

3) รสมาลิน ตั้งนพกุล. รักเอย. กรุงเทพฯ: สำนักพิมพ์อ่าน, 2555. [Rosmalin Tangnoppakul. Love Story. Bangkok: Aan Press, 2012.]

Amphon Tangnoppakal was arrested in August 2010 for allegedly sending four SMS messages with anti-monarchy content. At the time of his arrest, Amphon was 60 years old and a cancer survivor. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison in November 2011 and died from metastatic cancer after less than six months in custody. Rosmalin Tangnoppakul, Amphon’s widow, wrote Love Story | รักเอย, about their life together, his arrest and death, and her life after his death. First distributed as a free publication at his cremation in the tradition of Buddhist funeral volumes, the book was reprinted by Aan Press for wider circulation. Amphon Tangnoppakul’s death catalyzed a rare moment of public questioning of the justness of Article 112 due to the severity of his punishment and perhaps also the reflection of their own lives that many citizens saw in the searing humanity of his life and death.

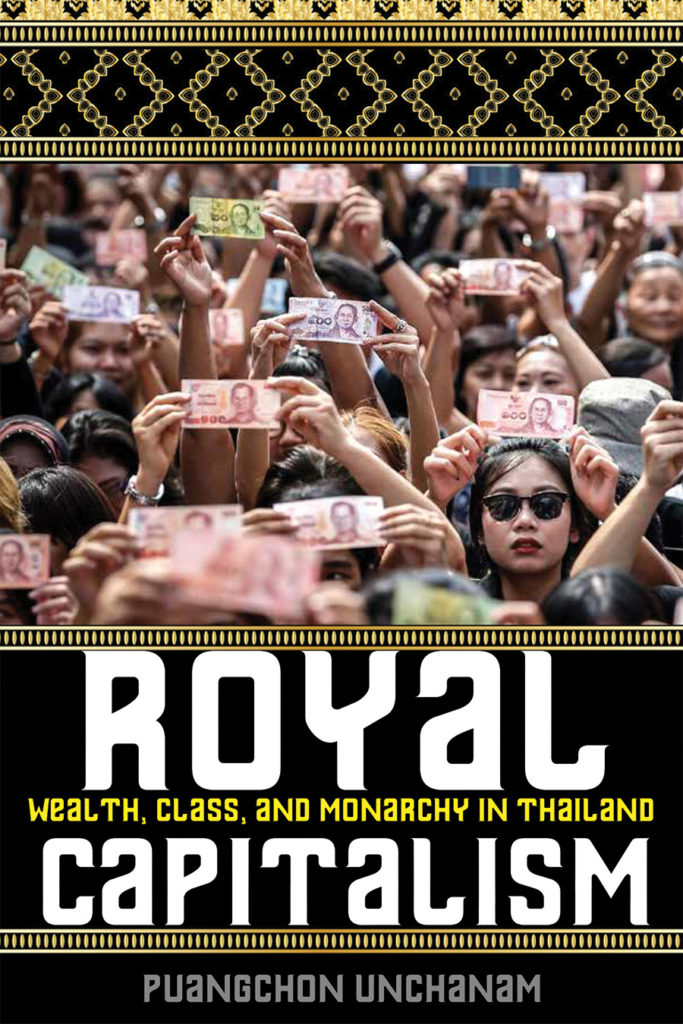

4) Puangchon Unchanam. Royal Capitalism: Wealth, Class and Monarchy in Thailand. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019.

A recent Los Angeles Times article notes that a conservative estimate of Rama 10’s holdings is $70 billion USD, an amount greater than the combined wealth of the British royal family, sultan of Brunei, and Saudi king. In Royal Capitalism, Puangchon Unchanam traces how Rama 9 created a machine of capitalist accumulation and reveals the dispossession of the people upon which royal wealth is built. The ubiquitous imagery of the king on the streets, in people’s homes, on calendars, and elsewhere helped create consent for this dispossession and even love for the king. Rewriting Marx, Puangchon develops a new understanding of the roles of the monarchy and the reactionary, rather than revolutionary, role of the bourgeoisie in political economy and social transformation. Theory here is no armchair exercise, but part of the critical work of critiquing society in order to be able to re-make it.

V. Imagining the Future

To dream of democracy in Thailand is to imagine a new, different future. To do so against the backdrop of years dominated by dictatorship and feudalism is an act at once daring, urgent, and hopeful. What are the futures imagined by those in the streets today? What do those who risk to dream wish to see, and what do they ask of themselves and us?

1) United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration. “Declaration No. 1.” August 10, 2020. https://prachatai.com/english/node/8709

On August 10, 2020, Panusaya “Rung” Sithijirawattanakul stood on a protest stage on the Rangsit campus of Thammasat University and read the inaugural declaration of the United Front of Thammasat and Demonstration (UFTD | แนวร่วมธรรมศาสตร์และการชุมนุม). The ten demands of the declaration called for a re-location of the monarchy in the polity and the remaking of the relations between the rulers and the ruled. Specific demands include an end to royal endorsement of coups, revocation of Article 112, reduction of the budgetary allocation given to the monarchy, and a search for truth regarding the nine republican exiles murdered since 2016. The declaration broke the taboo on questioning the monarchy and each protest since then has further pushed the limits of what is and is not speakable. For daring to make the declaration, Rung and her fellow activists have been arrested and detained multiple times since August. And yet they continue.

2) Patiphan Luecha. “A Song of Forgiveness Within.” Translated by Peera Songkünnatham. Read both the English translation and Thai original here. Listen to a reading of the English translation here.

Patiphan Luecha, also known as “Bank” Patiwat Saraiyaem, is a mor lam (northeastern folk performance that combines poetry, music and dance) artist. Along with Prontip Mankhong, mentioned above, Patiphan spent over two years in prison between 2014 and 2016 after conviction of committing lèse majesté while performing a play. He performed as part of a UFTD protest held on the 14th anniversary of the September 19, 2006 coup. In the subsequent wave of arrests, he was picked up on October 19 and held in prison for 12 days for his participation in the UFTD protest. While in prison, he wrote “A Song of Forgiveness Within,” which Peera Songkunnatham, who acutely translates and performs, describes as a curse against dictatorship. As Patiphan writes, “May the good deeds from my past/Come drive them out/And knock them down like bowling pins…”

3) สุพจน์ ด่านตระกูล. ปทานุกรมการเมือง ฉบับชาวบ้าน. นนทบุรี: สำนักพิมพ์สันติธรรม, 2528. [Suphot Dantrakul. A People’s Political Lexicon. Nonthaburi: Santhitham Press, 1985.]

Suphot Dantrakul was a leftist intellectual who wrote over 100 books between 1952 and his death in 2009. In 1952, he was arrested along with 103 other dissidents and accused of insurrection. Sentenced to 13 years and 8 months, he was released in a 1957 amnesty. Based on the lectures of fellow prisoners and spirited out in a cracker box, A People’s Political Lexicon offers perspectives on 43 keywords including class conflict, bourgeoisie, history, and law in which the people, not the kings, are central. Only one entry has been translated into English, law | กฎหมาย, in which Suphot notes that the ruling class writes the law for themselves. But he also notes that law and its allegiance can be transformed as political power shifts. As arrests continue and remain in the streets in Thailand, Suphot’s centering of the people and his clarity on the law remain instructive.

4) Everything that remains to be dreamed, written, created, and performed.

With each new day, each new protest, each new declaration, each new song, each new poem, each new short story, and each new essay, democracy is being imagined, put into practice, and called into being. This syllabus therefore remains incomplete, and space remains for the addition of new materials.