In Huan Hsu’s The Porcelain Thief, the search for a family treasure unearths the spell of nostalgia

January 15, 2016

The root of the word “diaspora,” the Greek word speirein, means “to scatter.” It speaks to the tension that binds and energizes a people uprooted: a single whole blasted and atomized into infinity. Huan Hsu’s work of personal history The Porcelain Thief retraces the Big Bang of his ancestry—the constellations of generations fanned across Asia and America, and the fragments of their lives left behind.

Hsu’s family lore includes a story of his great-great-grandfather Liu Feng Shu, who in 1938 fled his hometown of Xingang along the Yangtze during the Japanese invasion of China and buried his vast collection of antique porcelains deep underground on his estate. Like many other doomed refugees, Liu never imagined he might not ever be able to recover the trove, which was, for men of that era, a marker of eminent social and cultural standing. Like many others of the last generation of the Qing Dynasty, his final journey after the war was straight back to his ravaged home, to sit out the waning days of his China.

Seventy years later, Hsu, born in America to Taiwanese parents, becomes spellbound by that sense of inherited destiny and sets off on a quest to gather the detritus of a family sundered by war and revolution. His scavenger hunt leads him to scour Greater China for imagined family secrets. Over three years, Hsu assembles a brilliantly imperfect mosaic of survival, regeneration and a collective impulse to glaze over the past while never quite sealing the cracks.

Hsu gathers snatches of memory through the ramblings of cousins and various elderly relatives who unburden themselves of wartime memories with pain and pride. He passes through a string of urban and rural landscapes, from a fortress-like Shanghai office complex run by his authoritarian Evangelical Christian uncle, to a dust-caked inland ghost town where a vestigial artisan community of ceramicists still plies its trade amid mounds of supple earth and towering kilns.

Reassembling the fragmented storylines is an exercise of imagination as well as forensics; Hsu is continually stonewalled by local officials who are petrified of unearthing anything politically risky; some relatives hold back their words, not wanting to stir up long-buried trauma . But his questions are plainly innocent. He’s less interested in riches or scandal than in tracing where different relatives scattered and how they survived their sudden displacement and impoverishment under occupation—and later as refugees of war and revolution.

The story Hsu strings together begins in a euphoric moment of Sino-modernity, when his great-great grandfather’s generation and his young children helped seed a hybrid Chinese-Western literati elite. They proudly fused filial loyalty with bourgeois tastes and European education, and their appreciation and acquisition of antiquities—purchasing them by the case when the family was at the peak of its prosperity. From here the family’s porcelain collection starts to come apart, in tandem with the steady disintegration of the sprawling House of Liu.

Paralleling Hsu’s hunt for the mystery porcelain—a domestic artifact exploded by conflict and exile—is his painstaking excavation of the Liu family daughters. Departing from conventional histories of this time, the story he charts is anchored by three women, born around the time of the first Chinese republic between 1911 and 1921, who grow up in a bucolic village dotted with feudal sharecroppers and go on to study at a prominent Wellsley-style boarding academy—arming them with credentials that ultimately help them survive the war and find jobs overseas.

As Hsu stitches together jumbled memories, from their serene boarding school days to the harrowing flight to the inland capital of Chongqing to escape Japanese warplanes, he begins to shade in a history that resonates with his imaginary visions of the lost family fortune: as the family came apart, their estate crumbled but so did centuries of patriarchal tradition. Yet the baptism by fire of China’s mid-century social uprisings also steeled their identity as modern women, even as the sisters remained estranged after the revolution. They persevered with their Western education during the war years and eventually attained professional careers. Huan’s grandmother—a free spirit who flouted Bible study at her tony girls’ academy—trained in chemistry and lived a “blissful” single life in the vibrant Europeanized enclave of Macau, before the war pulled her into work at a mainland ballistics research laboratory. What the family lost in aesthetic refinement they made up for in their participation in China’s societal reconstruction.

As his elders’ stories come into focus, the prize Hsu seeks grows more elusive. In fact, the entire story unfolds without any actual physical description of the porcelain. It’s all wrapped up in the mystique of an imagined past, and seems increasingly frivolous against the backdrop of stories of bombs, torture and displacement. But amid the tales of trauma and chaos, his journey is punctuated by glinting flashes of beauty. The imperial relics, ceramic shards, and other craft works he discovers inspire the sentimental porcelain visions he reconstructs in his mind. He recalls in one scene a museum piece he encounters in his youth—a vividly glazed crimson dish from a past dynasty—that evokes a deep longing to concretize his own family’s inheritance:

The longer I looked at that red chrysanthemum plate, the more I wanted to touch it, feel its weight, and run my fingers over its edge, which, like its country’s—and my family’s—history, was anything but smooth.

His work of reassembling his family history, too, is hampered by the fracturing of memories. When he tries to extract details from his aging great aunt, he finds himself wading through a sea of broken recollections: “She wasn’t making up her memories, but they had unmoored from their original context and drifted into a mosaic with no beginning, end, or order.”

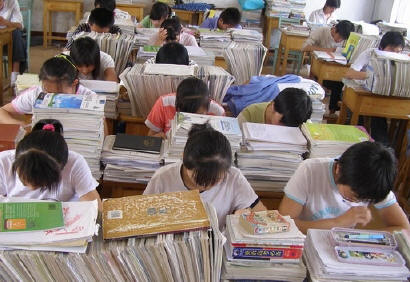

And Hsu’s montages of contemporary China are similarly disoriented. The modern and ancient constantly chafe against each other: tree-lined gated communities butt up against jagged plots of farmland at the city’s edge; Soviet-style factory smokestacks loom next-door to an expat-run studio gallery, where foreign ceramic virtuosos muse over shards of imperial teacups for inspiration. On this convoluted historical landscape, what Hsu seeks isn’t the delicate beauty of porcelain so much as the tension the objects represent—hardened by primordial fires and recast in translucent splendor. The same amalgam of strength and weakness suffuses today’s China, its identity shifting between a rising superpower and an inheritance of deep suffering.

Throughout The Porcelain Thief, Hsu seems to be racing against time to rescue the porcelain from social amnesia. Yet again and again, the historical nuggets he unearths reveal the irrationality of our nostalgia. On the last stretch of his odyssey, after reaching a parcel of land where he and a gaggle of relatives speculate where the porcelain might be, he hesitates before sinking his shovel in the dirt, second-guessing his obsession:

Maybe I had conducted this search the way I had—naïvely, indirectly, protractedly—because part of me wanted my family’s things to stay buried. Maybe I didn’t really want to know. I had created my own mythology, and maybe that was enough.

The Porcelain Thief is not exactly a mystery. The bounty resides in the fragile bonds of family, and in the impulse Hsu has inherited from his great-great grandfather; the patriarch’s fierce desire to protect his riches from the world was matched only by the determination of his progeny, three generations later, to uncover it. A turbulent history has by turns buried and resurrected the dream of stealing back hidden treasure. Every time a chip peaks up from the surface, it always beckons its rightful owner.

Michelle Chen: You begin The Porcelain Thief discussing your childhood fascination with the act of digging, finding things hidden in the ground. Why did you see that as a good frame of reference for a story about your quest in adulthood for your family’s long-buried treasure?

Huan Hsu: These are things that came out of the writing process. I was immersed in the research, and it wasn’t until I sat down and tried to make sense of what I did that I made that connection. I think maybe subconsciously the impulse to dig is connected to the impulse to look for stuff and I think that was probably something I was more conscious of, that I like to look for things. There is great satisfaction in both the search and the finding of something. I still remember when I was a kid that first time I heard the trope of “digging a hole to China”—from a cartoon probably or The Brady Bunch—I went to the backyard and tried to dig a hole to China.

How did you connect your personal fascination with porcelain with your great-great-grandfather’s obsession with collecting fine porcelain—and, more broadly, Chinese society’s deeper historical obsession with the art of porcelain?

I guess when I first heard about this story. I was in the Seattle Art Museum and had just stumbled into a room where I was looking at all of this porcelain. All I knew about porcelain was that the Ming vase was an indicator of great wealth in the TV and movies I watched during the 1980s and 90s, and so I didn’t necessarily have an appreciation for either the aesthetics or the history of these objects. Except for this one little plate [an artifact that he mentions being captivated by as a child upon seeing it in a museum exhibit]. There was something about it that was different—I think that the fact that nobody knew what the characters on that plate said really tied into that impulse of wanting to find something. And then when I got interested in the story of my family’s buried porcelain, I still didn’t necessarily, you know, love porcelain, as objects. I think even now, I’m definitely not a porcelain collector—there’s something missing for me I guess, compared to the people who do love collecting porcelain. While I was in China I wasn’t even looking for porcelain, I was much more interested in the shards that had gotten left behind from broken artifacts, because to me they were like the dinosaur bones of China. And they seemed to be charged with, I don’t know, a history of meaning that was much more accessible to me.

Let’s circle back to the plot. What exactly did you set off to do and at what point did you realize you were getting into something that maybe you had not anticipated?

When I first heard about the story, of course the writer in me was like huh, that would probably make for an interesting book. On the practical side of it there’s probably a market for this story and I feel fairly confident that I could write it. I mean I had never written a book or anything but I was like, okay, it’s like a really, really long feature piece. I was naïve when I went into it. I think I wrote in the book that I assumed I’d be in and out within a year. I thought this would be an elegant research trip, I thought I’d go there and get settled and work for my uncle’s company, I would learn Chinese on weekends and just, you know, get out there wandering around and talking to people and digging for the porcelain. Pretty quickly after I got to China I realized that it was a much bigger undertaking than I had imagined.

Part of me wanted to remain naïve about it. I think there were ways I could have expedited the search. I could have tried to take advantage of my uncle’s connections a little more, I could have tried to do things a little more through the official route. But I was also wanting to stay naïve because I wanted to see what a normal person would be able to do in China. I guess I just wanted an unalloyed experience of China; I didn’t want my search to be influenced by connections or things like that. When I think about the experience overall, I think of it more like a series of [incremental] realizations that this was going to be harder than I thought, maybe up all the way until when I actually had a shovel and was standing in the area where I thought the porcelain might have been buried on my family’s old property.

Even then it was just hitting me. “What did you think you were really going to be able to do?” I’m standing there with a shovel and there’s a hectare of land for me to try and dig on. I just had two guys in their eighties and me with some old digging tools—what are the odds that we were ever really going to find anything? Yet that didn’t stop me from trying.

I also thought about how insane it is that in China, you can just show up at this village 70 years after something had happened and just expect whoever was in charge of that land to say, “Yeah, go ahead and see what you can find.” I mean, what if the descendant of some Chinese guy who came to California in 1849 showed up in San Francisco today and was like, “My great-great-grandfather lived here during the Gold Rush, and I think he might have left something in your yard. So do you mind if I just dig around for a little bit?” It would be a very naïve request.

How did the research for this book change the way you view your family and your family’s history and your family’s attitude towards this past? There are so many instances when you speak to relatives and you kind of hit a brick wall or a blind spot. What did it tell you about the way your family in the diaspora perceived China and its history?

It was satisfying because I did feel like as I was visiting these estranged relatives, I was kind of reconnecting with them. I was bringing them news of how these other people were doing and we spent a lot of time talking about so-and-so I had just visited, and then I would go on to the next relative, and I would tell them about who I had just visited. I don’t know if my immediate family, like my mom and her brothers, are necessarily more interested in their own family history.

Looking for my family history was also a really great way of orienting myself in China. I would tell people I met that I was looking into my family history, and then it was really easy to ask them about their family history so it was a nice way to connect to people. A lot of times when you mention the family histories of people in China or of diasporic Chinese, there’s a lot of common threads in those stories. Because all of these stories to me were so fascinating, I think I’ve gotten to the point where I’m convinced that everyone has a fascinating family history.

It really disappoints me when I hear my white American friends say “Oh yeah, my family is so boring. I think my dad is Danish and my Mom’s Irish—whatever.” And I’m just thinking, you know they all came from somewhere! It’s bizarre that you think the fact that your ancestors crossed America in covered wagons to get to Utah is boring. But if you look past that time, there is some ancestral village where your family is from in Europe. And lots of stuff happened in Europe over the past couple of hundred years. There is nothing boring about anybody’s family history, so I think that I’m kind of disappointed if people express disinterest in their own family history, especially, members of the Chinese diaspora.

One thread throughout the story was the women in your family. I thought that was an interesting recentering of narratives that we don’t always see, in histories of war, often not even in family lore. Did that focus on women happen in your work because you happened to speak to more living relatives who were women, or did you kind of consciously try to focus on that?

I have to say, I don’t think I was conscious about that at all. It was just a function of who I was talking to and who the prominent members of that generation happened to be. My grandmother’s generation was mostly women, with several sisters and female cousins. I think there was only one male in that generation. So it was the women who were doing the interesting stuff and living through interesting times. There weren’t any other ulterior motives other than, I guess, that I had the hand I was dealt.

Can you talk about your grandmother and great aunts’ experiences during wartime and after the war?

My grandma and her sisters and cousins were all educated at a quite prominent missionary school in their hometown. It was a feeder school for a really prominent women’s college in Nanjing so they all learned English when they were young. That’s something I didn’t know, and something that my grandmother never let on when we were young—how good her English was.

They were all encouraged to be educated—not necessarily to be independent but to be more independent thinkers. To embrace whatever the west had to offer. They were all encouraged to be really open-minded about that kind of stuff. They all, in their own way, had really interesting lives. My grandmother was the one who really bore a grudge against her grandfather. She wanted to be a doctor, but as open-minded as her father was, he wouldn’t let her study medicine because he didn’t believe in a co-ed university. So he made her go to a women’s college. And this women’s college is really fascinating for me. It was set up to serve as the Chinese sister school for Smith College, so that was something that I could grasp onto. It helped me contextualize a lot of things [about the school] for me, knowing that it was a cousin to the seven sisters. The school used this western curriculum, and the only thing that was taught in Chinese was the Chinese language and literature class. This was where the Chinese nationalist elite would send their daughters. My grandmother went to school with some very prominent women. And then she went off to have her own adventures. When I met her again in her nineties, it was hard to imagine this little woman had decided after she graduated that she would go out instead of going home back to her hometown (which is what a lot of women did; they would go back to their hometowns and teach at their high school). She decided to go to Guangzhou and teach at a school there. During the war the school was moved to Macau, and she was just having a really nice life up until the war got really bad for that whole generation.

And because my grandma was the oldest, I think she was the one her sisters and cousins looked to when it came to their education. So for all of them, I don’t think it was a question that they would go to school.

You traverse this huge landscape, across different eras in Chinese history. I wonder if you came away with any thoughts about where contemporary China is going. I know you probably didn’t want this to be a huge tome about the future of modern China, but because the story is not just about your family’s porcelain it became kind of a metaphor for all of these contradictory strands of Chinese culture and society. What questions did these strands leave you with?

Yeah as much as the book is this exploration of identity, I did feel like I had some kind of reconciliation with China, because before I had gotten there, it was kind of this boogeyman. The way my parents or other Taiwanese expats would talk about the mainland, it was presented as this big, dark foreboding place, and of course you think about stuff like Tiananmen Square and the western media tends to be kind of negative about China—I think rather unfairly, much of the time. But yeah, I had a really dim view of China before, and of course when I first got there, I had an even dimmer view, because it was just so chaotic and confrontational and difficult.

I guess after having been there for a while and having lived there and done this book I feel like I’ve accepted it as part of where I come from, and I am glad that I’m Chinese and that I learned to speak Chinese so that I can navigate this place that is endlessly fascinating even though it is also very difficult. So I guess the analogy would be like accepting your family. You can’t change it, you can’t change who they are. You don’t have to like everything about them, but they’re a part of you and you get them. You accept them.

What did you ultimately feel was the biggest discovery that you made? You set out with a clear mission in mind, that this was going to be a simple, straightforward journey to uncover this particular aspect of your family’s past. But you ended up doing something quite different. So what did you take away in the end?

I think from the start, even though I fantasize and I continue to fantasize about finding this cache of buried porcelain that used to belong to my family, I also recognize that it was unlikely or it was going be extremely difficult to pull that off. And the real point of this exercise was the journey. I mean, its kind of a cliché, but I was just hoping that looking for the porcelain would give me an opportunity to experience China in a unique way. And in the end, I do find some antique imperial porcelain. It wasn’t necessarily how I expected to find it, or where I thought I would find it, but there is a kind of satisfaction there. Although of course, that discovery comes with a bunch of other questions that might never be able to be answered. But I think in the end the most memorable thing that I take away form this is the experience in China, and the feeling, or the understanding, that being Chinese is a privilege rather than a burden. That was what allowed me to wander through China in an interesting way, and I had the privilege of being able to travel through this country and meet its people and experience its culture with as much confrontation as I chose. I think towards the end, I realized that if you aren’t actively looking for confrontations all the time, the experience becomes even more rewarding.