It all started with Beijing rock band The Fly—a cross between the Sex Pistols and Nirvana, but, you know, in Mandarin.

July 10, 2012

It seems fitting that my introduction to Chinese rock would be through a random CD I picked up in a dollar bin in Brooklyn’s Chinatown shortly after 9/11. The CD was the 1997 debut album by pioneering Beijing punk band The Fly. The bin was outside of Xinhua Bookstore/Fantasy Audio & Video Inc. (8th Avenue just below 53rd Street) in Sunset Park.

Fitting because, after all, rock and roll in the People’s Republic took off in the late 80s to early 90s with the introduction of dakou (打口, “saw gash” or “cut out”) cassettes and CDs from the Western world—literally, remaindered discs and tapes intended for landfill but rerouted to dakou stores where people like Feng Jiangzhou, the Fly’s lead singer, got his first taste of the once forbidden music.

“I used to buy a lot of dakou cassettes,” he told scholar Jeroen de Kloet, whose book China with a Cut (Amsterdam University Press, 2010) chronicles dakou culture and the (relatively short) march of mainland rock and roll. “I studied the music carefully with all my heart. I conducted very detailed work.” Feng explained that in the first decade, between 1986 to 1996, “Chinese rock remained pretty much the same, basically hard rock. So I believe that from 1997 there should be something new. What I am trying to do is to create…the avant-garde in China.”

The Fly was, perhaps, a bit too avant-garde by the mainland’s standards, their lyrics too body-oriented and vulgar—

Since there is no light bulb in this village toilet

Since there is no full moon tonight

Since I can’t fall asleep

Since I want to play with myself […]

Under my ass shine rays of dawn

I will bring with me the shit fragrance that fills the hut

My nirvana, my nirvana

(“Nirvana,” trans. Jeroen de Kloet)

—and the band wound up having to get their first album released by a Taiwanese label, who then tried, unsuccessfully, to market the thing back to the mainland (which may go a ways in explaining how I wound up finding my own copy in a dollar bin outside Xinhua/Fantasy). It was finally released by a subdivision of the Beijing indie label Modern Sky two years later. In 2000, The Fly released their last album and eventually broke up when Feng abandoned rock for a far more successful career as a painter and video artist.

Over the decade I lived on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn, I rode my bike over to Sunset Park for Yunan noodles on 49th Street and cheap Hong Kong, Korean, Japanese, and Thai videos at Xinhua/Fantasy almost every other week, at least during the warmer seasons. It took me a few months before I bothered to look through the CDs; I knew nothing about music from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the mainland, and what they played in the store (most likely Canto-pop) did nothing for me.

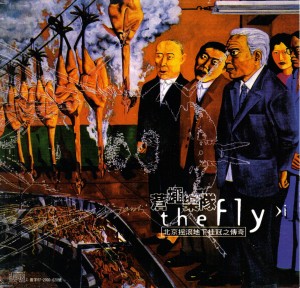

So I have no idea why, one day after spending a half hour or so combing through the DVDs, I paused in front of the dollar bin on my way out the door toward my bike. But I did pause and, in doing so, noticed a CD with cover art quite unlike anything else I’d ever seen at Xinhua: a group of Chinese officials in suits looking on as a row of upside-down dead chickens, suspended from their feet, seem to chug across the sky blowing massive amounts of smoke into the air. The painting was stylistically somewhat reminiscent of Diego Rivera, but simultaneously darker and more garish. Without even thinking about it, I picked it up, headed back inside the store, and gave the guy at the register my last remaining dollar.

I popped the CD in my player the moment I got home and was promptly blown away. You can listen to them here and here. While certainly not avant-garde by Western standards, the first song on The Fly I was almost excruciatingly visceral, a bit of a cross between the Sex Pistols and Nirvana (which may explain the title of the last song on the album). Over the next several years, each time I made an outing to Flushing, to Manhattan’s Chinatown, or anywhere else where Chinese-language pop music was sold, I made a point of bringing along the CD, desperately asking anyone who’d listen if they knew anything about this band and, more importantly, if they had anything else in stock by them. The perplexed, sometimes disgusted faces the shop keeps and register clerks would make, taking in the artwork and sounding out the name of the band in Mandarin, often told me their answer before they did.