Part one of a two-part series on local Asian-American engagement in electoral politics in New York City.

January 24, 2013

Part one of a two-part series on local Asian-American engagement in electoral politics in New York City.

On January 21st, Barack Obama took oath as President of the United States for his second term in office. In many ways, the victory of his second term cannot be extricated from the story of who voted for him and why. Among the factors was America’s changing demographics due to immigration, and the news media have already offered plenty of hypotheses on the preliminary exit polls that showed the growing Asian-American electorate greatly favoring Obama, in the range of 72 to 73 percent.

But a new set of findings released by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) shows that a higher percentage of Asian-American voters may have chosen Obama than previously expected, at 77 percent. AALDEF’s report, based on an exit poll of Asian-American voters in 14 states who cast ballots in the November 2012 presidential election, revealed many other trends and differences among Asian-American voters. The exit poll project sent hundreds of trained volunteers around the country, and they surveyed 9,096 voters in an effort to document Asian-American voter disenfranchisement as well as to analyze the factors that weighed in on their voting choices. According to Glenn Magpantay, director of AALDEF’s Democracy Program, most exit polls only survey a small proportion of Asian-American voters or only poll those who can speak English. But AALDEF’s survey is multilingual and conducted in 12 languages (English, Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, Bengali, Urdu, Gujarati, Khmer, Hindi, Punjabi, Arabic, and Tagalog). Their poll promises a more nuanced view of voters, broken down by age, ethnic group, geographic location, and political party affiliation.

Hearing that there was a need for Korean-speaking volunteers, I contacted the project and was dispatched on November 6th to monitor poll site JHS 189 in Flushing, where the community demographics necessitate language assistance in Chinese, Korean, and Hindi/Bengali. I waited outside the school with a clipboard in my hands, along with three law school student volunteers and Peter Lee, a staff member from MinKwon Center for Community Action who was supervising the afternoon shift of volunteers.

A changed landscape: New districts in Queens

Months before the election, Asian-American voters were deemed the Great Undecided (approximately 32 percent among eligible voters). We were the Forgotten (51 percent of Asian-American voters were never contacted by either presidential campaign), even though we were also the Fastest Growing Racial Demographic. Overall, Asian-American voters were shrouded in a cloud of anxiety as if, along with everything else, our voting preferences were unreliable. Were we present? Were we statistically significant?

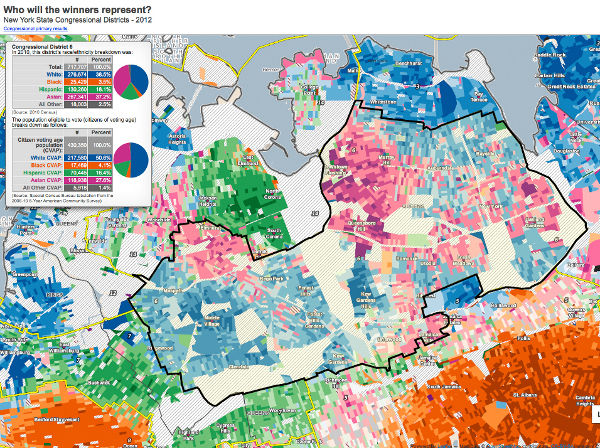

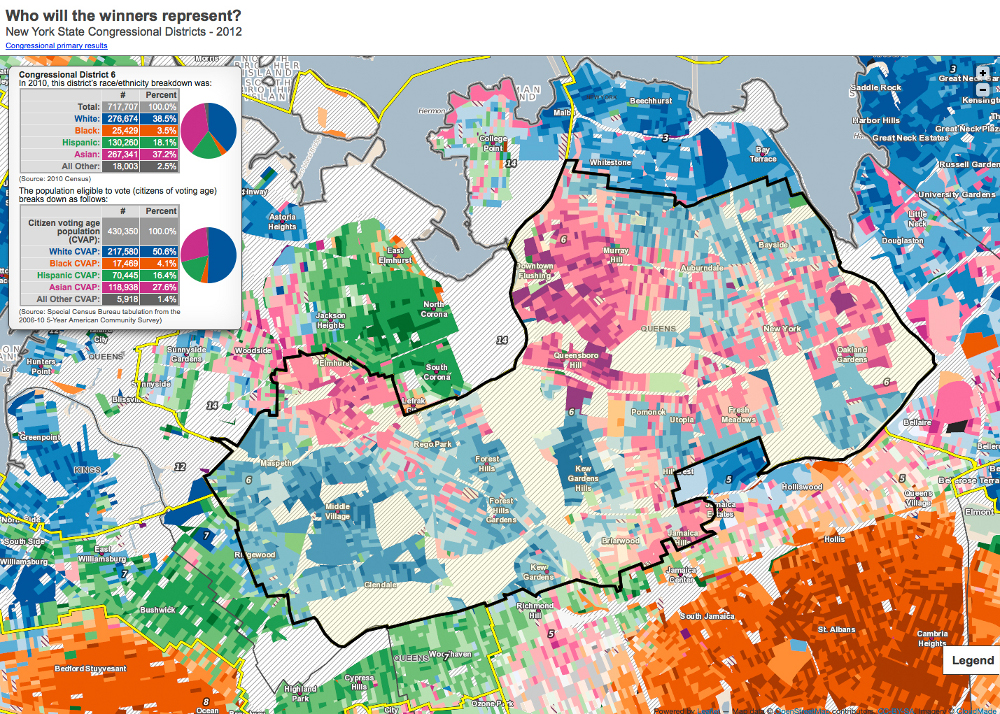

Yet in the streets of Flushing, election season had been blasting at high volume for months. Exiting the 7 train, buying groceries, sitting at home, a campaign might reach you, if only for a robo-call or radio ad trailing you out of a store. With State Assembly member Grace Meng (D) campaigning for a newly opened Congressional seat, her vacated spot led to a heated local race, with seven contenders in the September primaries. But what people were witnessing in the local races in Flushing was not a fluke; it was the result of advocacy for fair redistricting by an Asian-American coalition along with other community groups. This had led to new districts that united northeastern Queens communities. What did this mean for voters? “Better districts lead to candidates that reflect a community’s choice,” said James Hong, MinKwon’s civic action coordinator. “Such candidates have the potential to energize the community towards voter participation.”

Indeed, JHS 189 felt energized. The yellow lights in the gym illuminated a packed and bustling room. “I have to admit, spirits are high, since so many Koreans are running for office,” confided a Korean-language interpreter who worked at JHS 189 that day. He didn’t want me to use his name, so I will call him Mr. S. He had immigrated to the United States 35 years ago, and had worked as an interpreter for about half that time. He initially dismissed my question about the 2012 election being any different from other years. “It’s really all the same, maybe a few more voters, since this year is a presidential election,” he said. But then his face brightened up and he admitted, “So many Koreans and Asians running! I’m telling you, the mood is good!”

A poll site with history

At the gates of JHS 189, I called out in Korean, “Please participate in our voter survey,” to the Korean-American voters leaving the school. Some looked confused and continued walking away. A few breezily lied, “We filled it out before we went in,” and sailed on, while others yelled, “I voted Democrat all the way, ok?” over their shoulders. A few paused, squinted at the form I held in my hands, and said, “Well, let’s make it quick then.”

I understood. It was cold outside. So by the light of a hand-held flashlight, I quickly went down the list of questions. (For this story, all of my conversations with Korean-American voters and poll workers were spoken in Korean.)

“?? ???? ????????” (When did you become a U.S. citizen?)

“??? ?? ? ????? ????? ??????” (Do you prefer voting with an interpreter and/or translated materials?)

“??? ??? ????? ?? ??? ??? ??????” (What were the most important factor(s) influencing your vote for President?)

In the 2005 and 2008 elections, the JHS 189 poll site had been singled out for discriminating against Asian-American voters and giving incorrect information to voters; in one instance, Chinese-American voters were rushed through the ballot before they could finish reading their instructions and materials.

“When I got assigned to JHS 189, my coworkers were looking at me like they were sorry for me. Partly because 189 is notorious for having a lot of trouble—so I was going in with my game face on, ready to meet hostilities,” said Lee, the exit poll supervisor for the afternoon shift. “For example, the people running that poll site, they always call the cops on us even though we have the right to actually be inside the building. This year, I didn’t feel any of that.”

Overall, the mood at JHS 189 seemed calm, even though the lines were long. Chinese-language interpreters actively greeted voters near the entrance. Mr. S., the Korean interpreter, pointed around him and said that he knew most of the other poll workers and many of the voters themselves. These poll workers knew what they were doing, he assured me. This was not true citywide, however. According to AALDEF, many poll workers had not known about Governor Cuomo’s executive order allowing New Yorkers to vote by affidavit at any polling site. In Chinatown, poll workers were also unaware that affidavit ballots were available in Chinese. Thus, many Asian-American voters in Manhattan Chinatown, Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, Jamaica, and Flushing were not given provisional affidavit ballots and turned away.

The voters

“I voted Democrat all the way, but…” and here a middle-aged Korean-American voter lowered her voice and glanced over her shoulder, “my husband voted Republican.”

Her husband stood away a few feet away, seeming to ignore us.

An elderly Korean-American voter emphatically answered, “Health care!” when I asked why he had voted for Barack Obama. When I asked voters about their views on comprehensive immigration reform and a path to citizenship for the undocumented, many Korean Americans and South Asians said: “strongly support.” A Pakistani-American voter looked appalled when I asked the required question: “Is this your first time voting?” “Of course not!” he declared, clearly affronted. In between surveys, a Korean-American campaign volunteer for New York State Assembly candidate Ron Kim (D) kept coming outside to query us. “Is it 400? 500? What’s the total tally of Korean voters?” We couldn’t answer her question, but she walked away, nodding with satisfaction. “It’s looking good, looking good.”

“Oh, my wife?” said one Indian-American voter, an elderly gentleman, when I gestured to her and asked if she would participate in the survey as well. “Well, she voted exactly the same as I did!” The woman next to him, wrapped in a thick coat and headscarf, smiled and nodded. They turned to leave. I had so many questions—(Was it true? How did spouses negotiate their political differences if they had any, or did they avoid the topic?)—but the night was cold, and people didn’t want to linger. No one I spoke to reported any discriminatory incidents.

Flushing/Bayside Korean voters at a glance

Koreans made up 11 percent of the national exit poll conducted by AALDEF. The stats: 20 percent were first-time voters; 60 percent were registered as Democrats; 14 percent were registered as Republican; and 24 percent were not affiliated with either party.

Last November, MinKwon also released a report to the Korean media based on surveys of Korean-American voters at five poll sites in Flushing and Bayside, using the results from AALDEF’s survey and an additional questionnaire about the local races. Flushing and Bayside are two adjacent neighborhoods in Queens that have seen great increases in their Asian population, with Flushing’s Asian population growing by 37 percent in the last 10 years and now making up two-thirds of the total population. Bayside similarly experienced an influx of Asian-American residents, especially Korean-Americans.

Of the 385 total Korean-American respondents in MinKwon’s report, 76 percent had registered as Democrats—higher than the national average; 15 percent as Republicans. Eighty-three percent of these voters had chosen Barack Obama as president—higher than the 78 percent of Korean-American voters nationwide who had. Nearly half indicated that they supported Obama because of his stance on civil and immigrant rights.

In this group of Korean-American voters, 74 percent backed comprehensive immigration reform, while 10 percent opposed it. On this topic, Lee shared, “What I found interesting when I talked to people in their 70s who had been here for a long time was that a good number of them were very pro-immigrant, but then another portion was very conservative. Because they’ve lived here for so long, the immigration issue has become someone else’s story.”

I also noticed that many of the older Korean-American voters we queried were not supportive of marriage equality for lesbian and gay couples. Elderly voters seemed especially vehement when I asked them the question. MinKwon’s report showed that 77 percent of Korean-American voters polled opposed marriage equality. However, a much higher percentage of younger Korean-American voters (18-49 years) supported it.

On the issue of language access, most of the Korean-American voters I spoke to said their English reading ability was moderate—workable for everyday life, but not great. Some hesitated in answering whether they had needed or used Korean-language ballots, but then shared that they had used them. Roughly a quarter of the Korean-speaking voters MinKwon surveyed said that they did not read English very well, and roughly half (48 percent) said their level of ability was moderate. This was despite the fact that more than 65 percent of the respondents had been citizens for 10 years or more. This is also reflected nationally, where 41 percent of Korean Americans speak English less than very well and nearly 70 percent speak a language other than English at home, according to the 2009 American Community Survey.

Nationally, nearly half of the Korean Americans in AALDEF’s survey relied on ethnic language media as their main source of news, the highest percentage among the nine ethnic Asian groups polled. MinKwon’s report did not have a comparative figure for the local community, but of the voters I spoke to, only one Korean American read English-language mainstream news.

Of the Korean-American voters who reported a problem at the five Flushing and Bayside poll sites, 7 percent said they had no interpreters or translated materials. Overall, being able to use English-language voting materials seemed to be a point of pride for many voters, but the need for Korean-language materials in the area was overwhelmingly apparent.

The volunteers and poll workers

Beyond the issues of voter disenfranchisement and political interests, the elections also brought out other differences within Asian-American communities. This story would be incomplete without talking about the AALDEF exit poll volunteers and the poll workers themselves.

Some of the exit poll volunteers were themselves ineligible to vote. For MinKwon’s DREAM Act organizer and youth program coordinator Emily Park, who supervised the morning shift of volunteers at JHS 189, this fact did not deter her from participating in months of voter registration efforts. She, along with Lee, had joined United We Dream’s DREAM Voter Campaign, which asked voters to sign a pledge that they would vote for candidates who supported comprehensive immigration reform and the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act, commonly known as the DREAM Act. The New York State DREAM Act is expected to be re-introduced this month and has bipartisan support in the state legislature. Park explained, “This DREAM voter pledge was for me one way to speak for myself and tell people, this is what we need, and I really want you to make sure that you not just vote, but speak on behalf of me. That’s a very empowering experience for me and a lot of other people.”

The Hindi-language interpreter at JHS 189, Aarti Dhamdhere, was not eligible to vote either. She had come to the United States from India only eight months before to join her husband. When I approached her, she immediately pointed out, “There was only one person for all of the Hindi speakers! I did my best with the Bengali and Punjabi speakers. I even helped the Spanish speakers; there was no interpreter here.” All told, she reported that she had guided 40 to 50 voters through the polls.

Why had she volunteered as an interpreter? Dhamdhere beamed. “I’m new in this country, and I’m very interested in the elections.” She told me she was a full-time homemaker, but was looking for a job. When I asked what kind, she said, “Any job. A good job, a government job.”

For the door clerk, Lorenzo Quindoy, this was his fourth time as a poll worker. He told me he liked being a door clerk, a position that involved guiding voters with accessibility needs. He was also looking for work. He had been an accountant, but had resigned to take care of his elderly parents, both of whom were immigrants from the Philippines. He had begun looking for work last year after his parents passed away.

Was being a poll worker a good way to earn additional income? Mr. S., the elderly Korean-language interpreter, scoffed at the notion. “A 14-hour work day—it’s forever, I’m telling you! You don’t do this for the money.” He shook his head. “Every year I want to quit, but it’s like the pain of pregnancy. You forget all about it. Then they call me up again, and I go.”

After the polls closed, I went to a friend’s house and watched the rest of the national election coverage. Of course, the main event of the night was the presidential election. But I knew there were many people holding their breath for the local Queens races.

When the results came in, Grace Meng became New York State’s first Asian-American representative to Congress. Ron Kim, an avowed supporter of the New York State DREAM Act and a Seoul-born immigrant, became the first Korean-American lawmaker in the state, and Democrat Nily Rozic, who had actively reached out to the Asian-American constituents in her majority Asian-American district, was triumphant with two-thirds of the vote.

What elections reveal (and don’t reveal)

That election night, I was struck by the evening’s juxtapositions: exit poll volunteers who couldn’t vote and new immigrants providing language assistance for voters. I had spoken to long-term immigrants who supported the extension of equal rights to undocumented immigrants but not to lesbian and gay couples. The younger poll workers I spoke to were seeking more sustainable employment, but took the 14-hour workday in the meantime. And then there was Mr. S., the Korean-language interpreter, who compared election work to the pain of giving birth, but had done so for 15 years without fail.

On the news, I watched the winning candidates thank their hardworking campaign staff and field volunteers. But beyond these clips, there was little recognition for all the work that had gone into making the playing field a level one. For Asian-American advocacy groups, ensuring fair elections had also involved fighting for fair redistricting, creating bilingual voter guides, registering first-time voters, and litigating the unfair treatment of voters in past elections.

More than anything, AALDEF’s national exit poll revealed that both locally and nationally, Asian Americans had voted for a change in immigration law. Almost two-thirds of voters in AALDEF’s exit poll, regardless of party affiliation, supported comprehensive immigration reform and a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. For the first time, many voters, regardless of their own immigration status, took the pledge to be DREAM voters, supporting candidates with progressive immigration views.

In addition, while most news reports of Asian-American voters drew generalizations from the Pew Research Center’s 2012 report “The Rise of Asian Americans,” broadly painting the Asian-American electorate as highly educated, professionalized, and economically ascendant, the AALDEF poll revealed that nearly a quarter of polled voters had no formal education in the United States. Further, 30 percent relied mostly on Asian-language news sources and 37 percent read English at a moderate level or not well. Twenty-seven percent had voted for the first time. And while Asian-American college students had high rates of voter enrollment, this was not true for those attending community colleges and trade schools, revealing a class divide in who was participating in elections.

For the 249 Asian-American voters who were wrongfully asked to prove their citizenship, the 183 who had no interpreters or translated material when they needed them, the 307 whose names were missing or misspelled on the list of voters—they represent only a fraction of the whole. Who else had been unable to vote or intimidated in the process? And in future elections, who will continue to speak for those who can’t vote?

While it remains to be seen how every winning politician will fulfill his or her campaign promises, there will be those who will hold them to their words long after the polls have closed. They—the community organizers, the civil rights groups, the neighborhood coalitions, the committed citizens—will be the ones to remember what President Obama said about our flawed polling system: “By the way, we have to fix that.”