Parkway itself will lose its luster, its sense of magic ascendance. And I will begin my struggle to understand this twin heritage—luminous freedom and oppressive grievance.

June 5, 2014

[Editor’s Note: We’re excited to present a second excerpt from Marina Budhos’ memoir in progress, “The End of Everything,” about growing up in Queens before it was the culturally diverse borough it is today. The essay appears in two installments. Part 1.]

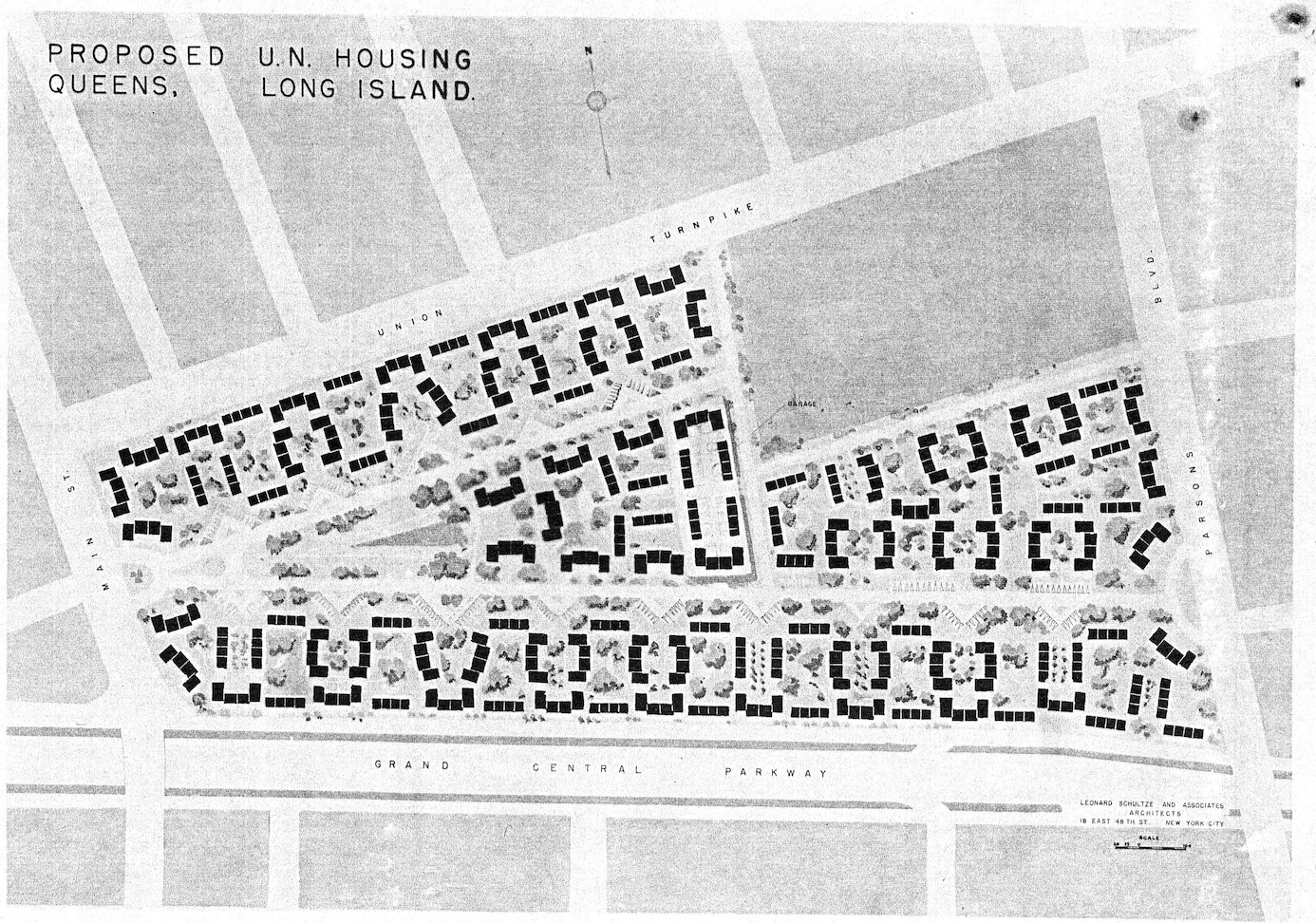

Parkway Village was created with the bold stroke of a pen, a phone call, yet another wheeling dealing moment in Robert Moses’ feverish, imperious imagination. That was many years before we moved in, back in 1946, when William O’Dwyer, mayor of New York City, was lobbying heavily to keep the newly created United Nations headquarters in the city. He had just four days to come up with a deal that would please the UN delegates. Up to the last moment, it looked as if Philadelphia might edge out New York City, as there was no obvious swath of land to erect such an ambitious headquarters. Moses tried to persuade the U.N. delegation to make use of the 1939 World’s Fair grounds in Queens, having already converted the old skating rink to a General Assembly auditorium, at a cost of $2.2 million dollars, a sleek, modernist central plaza with flags flying all around.

The UN delegation was firm in wanting a central, Manhattan location, and so Moses picked up a phone, made a few calls to important power brokers such as Nelson Rockefeller, real estate baron William Zeckendorf, and he was able to promise headquarters along the East River. And housing to the U.N. through three entities—Peter Cooper Village, Stuyvesant Town, and Parkway Village. Of the three, only Parkway was explicitly non-discriminatory. (Stuyvesant Town, a huge apartment complex that stretched alongside the East River of Manhattan, would be a legendary stain on planned middle class housing, since Metropolitan Life explicitly forbid ‘Negroes’).

It is somewhat surprising that Moses, a difficult man known for his hostility to civil rights–who built few playgrounds in poor, minority neighborhoods, and created the sweeping Riverside Park to end in ugly steel girders that slashed shadows across black Harlem–would create this a small haven of interracial living, where people of all races were welcome. But Moses was also a pragmatist who would pull whatever power levers he needed to bring the prestigious UN to the city, crowning New York as a world-city. Moses saw the UN as a symbol for the progressive, shining new.

By now, Moses had created bands of highway that circled and re-circled Queens like a lavish embroidery quilt. The plot of land on which Parkway was created was right next to the Grand Central Parkway, a thundering surf of cars that swept past in a sunken shaft. Less than half a mile past Parkway, that highway forked into the stream of the Van Wyck Expressway, each of these highways ribboning the hour-glass of Flushing Meadow Park, where the World’s Fair grounds lay, then heading north toward either the Whitestone Bridge, or the Triborough Bridge, his most mammoth of bridge-projects. Or, one could head west on the Grand Central Parkway and go straight to the suburbs of Long Island or Jones Beach—another Moses creation.

To grow up in this landscape is both strangely secure and unsteadying. There are so many highways, stippled bands of movement surrounding us, that I often feel we are impermanent, a blur on the way to the real America. Queens is parceled into neighborhoods of neat, shingle-one-family houses or six-story brick apartment buildings; where people have arrived, fresh from the tenements of the Bronx and Brooklyn; where their children, often the first or second generation egged toward college, can go to decent schools in red-brick school buildings. With those highways thundering past, it’s as if Queens is a stopping off place, on the way somewhere else, that far off suburban America, just out of our reach. We are never quite arriving, in a state of circling, like the airplanes that hover over us in flight patterns from either JFK or LaGuardia.

Parkway always carried a whiff of utopianism-it is different, a place declared an end unto itself, resisting the tumbling post-war highway energy urging people toward the suburbs…

Just to the west of us, on the other side of 164th Street, is a neighborhood called Utopia. The name harkens back to the turn of the century, when a chunk of land was bought to create a cooperative for Jewish families on the Lower East Side. That utopian community was never built. But ours, so nearby, was. And it points to the sense that Queens—a long stretch of flat farmland–as a kind of tabula rasa, the place where one fled the dark, cramped past, to carve new lives.

Parkway always carried a whiff of utopianism-it is different, a place declared an end unto itself, resisting the tumbling post-war highway energy urging people toward the suburbs, with individual houses and yards. The philosophy was there, in the design itself, for Moses turned to the famous firm of Shultze and Associates. As architects, they first made their mark with some of the most famously lavish hotels—the Waldorf Astoria and Pierre in New York City; the Breakers in Miami–but by this era, after the war, they came to be known for creating sustainable, ‘cities within cities’, planned rental communities that were needed by World War II.

They chose a gently hilly, triangular, 40-acre plot that was once a farm, now girded by the busy thoroughfares. With its matching, trim colonial buildings, its tall porticos with ionic columns, the complex resembled a bucolic college campus. Once you passed through the stone entrance pillars, you felt you were entering not academic quads, but your own inner refuge.

Even my address—on Charter Road—reveals our UN origins–named after the UN Charter. Everyone knows each other by courtyards—Oh, do you live by the Circle? The Green? On the Village or the Charter Road side? Tribes of children rove up and down these private roads, coalescing, regrouping, surprised by the discovery of yet another group, one courtyard over.

The long buildings, arranged around an oval of grass, with their white columns and cornices, seemed to be in conversation, encouraging an easy, back and forth rhythm between neighbors. Barely a third of the plot was used for the actual buildings, gently accommodating the little dips and valleys in the land, avoiding the straight-line bulldozed feel of so many post-war complexes. For us kids, this means all kinds of pathways; steps built into irregular hills, so we can run from one courtyard, down to a playground or yard, continue onward; it means excellent slopes for winter sledding, and nooks and crannies to hide in.

We children often stay out late, riding our bicycles down the private roads, wave and call out to rivals and friends, while the adults congregate on patios or porches. We grow used to saying good-bye to our friends who live among us for a few years until their parents are posted to another country. Parkway was a concept born out of the belief that a community could be molded, created from scratch with just the balance of privacy and shared space. It has worked: they have sealed us into a new kind of identity, a local village out of world origins.

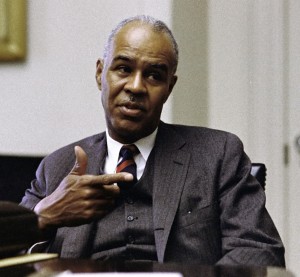

One of the earliest residents in Parkway was Ralph Bunche, the African-American diplomat who negotiated the 1949 Arab-Israeli truce, for which he would eventually receive the Nobel Peace Prize—the first man of color to have won. He was the perfect, emblematic figure for Parkway: worldly, gracefully successful, a true internationalist. Bunche would eventually leave the community—his wife, who endured his long absences–longed for a solid place they could call their own, so they bought a house not far from Parkway in the leafy, shaded streets of Kew Gardens.

During the fifties, Parkway blossomed into an oasis of integration and international cooperation; it made the pages of the New York Times and local newspapers. Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Truman came to visit the nursery school—a cooperative created by the mothers; Paul Robeson’s wife used to show up for parties. And there was Betty Friedan who lived here as a young newlywed and led a tenant’s strike; she would later recall her Parkway years as the happiest of her life—the impromptu communal meals, the nursery school, the very air made up of brotherhood and equality. The Latin American writer Ariel Dorfman would also remember Parkway Village as a kind of international paradise, before the chill of McCarthyism drove his leftist father out of the UN, and out of the country.

And then of course there is Roy Wilkins, head of the NAACP, the National Association of Colored People, who lives in the building kitty corner to us, whose windows I can just make out from my own. We are all aware of the tall, quiet, elegant man who marched with Martin Luther King and helped usher in the 1964 civil rights legislation. Sometimes Mr. and Mrs. Wilkins take their walks on Sundays—he always seems to be wearing a long black coat, often with a white shirt and tie underneath, as if dressed for a funeral or church. We children smile, wave shyly, and the two give us beneficent, slightly removed smile back, as he steps into his black Triumph. Wilkins’ moderate politics are true to the ethos of Parkway: this is no radical, fringe utopia. Parkway families are pioneering, but in a gentle, quietly forceful way. As we scramble and play and listen to folk and rock music on the Village Green, he is the kingly, removed figure, anointing us children as something different, special; the public pioneer who makes us all possible.

By the time my family moved in 1964, there were other parents, too, perhaps not as famous, but caught up in that early sixties moment of New York City, media, internationalism and politics. My brother, who was nearly eleven when we arrived, swiftly became friends with the half-Japanese Colton brothers, Jimmy and Jay. To me, they were the most beautiful boys I had ever seen. Every time they showed up at our door, I went wordless. My breaths stopped. My chest ached. They seemed utterly perfect, with their shock of straight black hair, their serene, ethereal faces. How could boys be so beautiful?

Their father had been a war photographer, then a photo editor at AP; their Japanese mother was the first Asian and first woman to be a photo editor at Time magazine. They grew up in a stylized home of artful Japanese arrangement, along with photographs, their apartment filled with signed books and prints, among them the iconic marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. To me, they were quintessentially Parkway, the pure and beautiful essence of mixture.

Parkway Village is not on any official map—we are a green triangle, bordered by Main Street and Parsons Boulevard, with no streets or numbers shown within. The police are not even allowed to come in to the complex, unless called by a resident. And so we exist, just uniquely ourselves. Perhaps this contributes to the languor and pleasure of this night, of so many of these nights, as I snuggle deeper into my scratchy afghan; the sense that we are protected, hidden under the huge trees.

Yes, we were not even on the map. But to me, we were the center of the world. We are what is to come.

* * *

“Time to go in!” my mother abruptly declares.

“Already?” I ask, hurt. My mood falls, like a sudden temperature drop. I’ve only just settled into my lounge chair.

“Yes,” she says, irritated. I see her face shut. She clanks her folding chair against her knee. “Your father has to teach summer school tomorrow.” Her tone is heavy, as if to impress upon me that there’s no more time for girlish dreaming—there are responsibilities to be faced—tomorrow, forever.

Abla Farghal laughs. “Maybe again tomorrow, sweetie. Insallah.”

I feel sore, cheated; whittled back down to a little child. Not only is my Tab half done, but my craving for grown-up talk is unsated. Good night, good night! everyone calls as they gather up their chairs.

Her tone is heavy, as if to impress upon me that there’s no more time for girlish dreaming—there are responsibilities to be faced—tomorrow, forever.

It is like the sap of night receding: I watch Helene head toward their place—she has a sway-hipped walk, her sandals flapping at the back of her heels. The Farghals also depart, Mahmoud, the husband, dipping his head under the round orb of a porch light. He is like my father, a little clumsy, boyish, lost in his work.

Then I hear my mother murmur, “How can Helene talk about South Africa that way! A place where my husband cannot even be served in a hotel? The nerve!”

My father grunts, affably. “Oh well,” he shrugs. “She likes it there.”

My whole body tolls indignantly, upset that with one remark, our magical communion with our neighbors is now in pieces, gone. A new, but familiar rage surges forward in me, white-silver, electric. My heart contracts. It’s as if I have been hurtling on one of Moses’ highways of possibility, only to come to a screeching stop in our private conversation, a judgmental shutting down. All around lies the smashed metal of grievance. At twelve, I am beginning to sense the prison of my family’s perceptions. For my mother, the world, other people, will always somehow disappoint. For my father, there is only trudging duty, a haunted past.

This is the paradox of my family, my upbringing—Parkway, with all its big, bold ideas—but we too had our undertow. For just as the night is draining, so too is the luminous influence of this place, this family, a silver orb slowly dimming. I know, instinctively, that I am at a cusp moment. I am twelve, on the uncertain edge of teenage. Perhaps like the dying man, hovering at death’s door: that I too will not want to remain, cozily meshed with the grown-ups, under the scratchy afghan; that I will soon leave this little square of warm porch light. And my parents, coiled tight in their gnarled history, will start to spiral apart, and my family will eventually shatter, bitterly. Parkway itself will lose its luster, its sense of magic ascendance. And I will begin my struggle to understand this twin heritage—luminous freedom and oppressive grievance.

I gaze across the darkened courtyard into the window of the man who is dying. My heart squeezes tight. I am suddenly bereft, coldly alone in the waning night. A chill grazes my soles. Is that death itself, urging me faster, towards the future?

Not yet, not yet, I whisper to myself. Not yet.

Moths tick against the porch roof light. My knees lock. I stare harder and harder, try, desperately, to make time stand still.

I see us now, perched in this graceful summer moment of pure, stilled perfection: brick buildings sunk in verdant green; neighbors hurrying across, impromptu meals of Arabic and Indian food; rickety go carts hammered out of found wood, flexible flyers skidding down ice-slick hills; international festivals on the Village Green, children streaking around the parents in folding chairs, foreign mothers, their iridescent saris swishing like tropical fish in the dusky tank of summer air. The boys starting to strum folk songs, later plugging in their electric guitars under the murky street lights, the sounds turning purplish and gaudy; anti-war posters and photos of gaunt, hollowed children in Biafra; the chink-chink sound of coins dropped in our orange Unicef boxes.

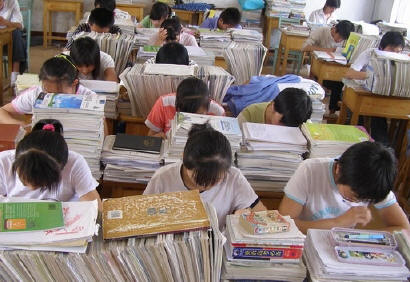

Every current will spark, take hold in Parkway. We are immune to nothing—the Vietnam War, elections, race, feminism, rock n’ roll. In the basement laundry rooms, next to the churning washing machines, the older kids talk Che, spin out mimeographs, plot revolution. The more liberal parents march for peace, for integration, suck on joints, try a few a few mod experiments in their marriages.

In the basement laundry rooms, next to the churning washing machines, the older kids talk Che, spin out mimeographs, plot revolution.

By the time I am old enough to ride around Flushing Meadow Park, the American pavilion in the old World’s Fair grounds is crumbling, its escalators inside stripped of rubber, a creepy place where local teenagers smoked pot. The tiles have fallen out of the beautiful mosaic inside the curved interior of the roller rink, and the rotating restaurant at the top of the New York State Towers is used for a chase scene in McCloud, a TV cop show. Our Parkway apartments echo empty, we in our suede clogs and feathery haircuts watching our mothers wobble off, to find who they could be.

That’s why I do not want this luscious, summer-time moment to disappear. I want to savor this particular existence, this time, this place. Not yet, I plead. Already I can sense the dispersal of my home, my family, the peak moment I was born into. I feel it like a cool undercurrent in warm, swampy pond water.

And so I linger here just a little while longer, treading, savoring the concentric circles that still pull toward us. The airplanes from LaGuardia and JFK airports track across a pinkish-dark sky, knowing that a bigger story lies here, deep in these Parkway nights.

* * *

Forty years later, I am driving back to Queens, my fingers resting light on the wheel, and can almost steer with my eyes closed, purely by memory. The streets, the curlicue ramps where the Grand Central and Van Wyck splay together, the bland sixties motel with its ugly stamp-like windows on Union Turnpike—all the same. Still the same low-slung buildings; the six-story apartment houses, the shingle homes with tight back yards; the broad post-war boulevards and whooshing highways.

And yet the Queens of today could not be more different than my own childhood home. No longer are these streets menacing, homogenous, shut-in, segregated enclaves. Queens has become a shiny poster child for international and immigrant America, a borough were 170 languages are famously spoken. Strung along the Flushing Number 7 subway line, are Dominican, Peruvian, Greek, Indian, Bangladeshi, Egyptian neighborhoods. Whereas my mother used to scour the city for spice shops, now the sacks are piled high in the stores of Jackson Heights. Downtown Flushing is a litter of Korean signs and businesses. There’s even a little Guyana—where my own father was from—tucked into Richmond Hill, a neighborhood where my brother and I never went, scared of the rowdy Irish bars where a dark-skinned kid was definitely not welcome. The fabled Unisphere is almost a cliché, a familiar trope of globalism, where every weekend soccer players from all over kick balls under its girded shadow.

Whereas my mother used to scour the city for spice shops, now the sacks are piled high in the stores of Jackson Heights.

As I turn through the concrete pillars, I have the sudden thought that our president, child of a Kenyan graduate student and an idealistic American girl, could easily have grown up here, on these shaded streets—an astonishing fact I would never have predicted, those long nights in Parkway, relishing our uniqueness, our isolation. One could say the Parkway dream succeeded; it predicted our moment of now.

One can see traces of the old idealism: a plaque for Mr. Wilkins, outside his former apartment. The fact that Parkway Village is now on the National Historic Register, for its place in history. Yet Parkway—the place–seems shrunken, smaller, even a little shabby. The Greek porch columns where I sat on that pink-sky night, are peeling, its hedges shaggy. The courtyard feels ominously quiet. Heading toward the playground, I see the open backyards are cut up with fenced in patios, since the community is now a private co-op.

Were we as crucial as I imagined? Was this simply the distortion of childhood, where everything looms huge, so wondrously significant?

As I wander up and around the silent paths, pausing in the old playground, a familiar certainty, an adamant sense of identity and memory, rises up. Surrounding me are those long brick houses, one after another, running in a parade of courtyards as far as the eye can see. Every one of these houses, with their shuttered facades, staring down, protecting us, bearing witness to a remarkable moment in time; a little capsule of history, of the future.

We were born out of an era of everything—the big romance of our parents, big ideas, plans and changes in a post-war, optimistic landscape. And we were the children of this vision. We could not have existed, together, if it were not for Parkway, if not for this dream. To be raised here meant being lofted out of the dark past, to be part of a sweet, idealistic moment, safely insulated from prejudice. Parkway allowed us to live in an in-between, where we did not have to choose one group over another. It was our oasis, a refuge of racial integration, where the stark divisions of the outside did not intrude. Beyond lay the slightly menacing, parceled ethnic neighborhoods.

Parkway allowed us to live in an in-between, where we did not have to choose one group over another…Beyond lay the slightly menacing, parceled ethnic neighborhoods.

We were at the center of everything, at a time when everything was surging with importance, raw newness. Somehow, despite the state of this forlorn, aging complex; the fact that neighborhoods, cities, move on, there is a crucial story to be told here. It is not just me, nostalgically fingering the metal monkey bars; it is not the simple remembrances of us grown-up Parkway kids—all of whom speak fervently, fondly, of their upbringing in Parkway as something special, unique. It is not in a plaque, or a facile slogan.

Before the Unisphere became a prescient symbol of our cosmopolitan nation, we were just kids, bicycling these streets, hanging out in playgrounds, learning to live with children from all over; adjusting ourselves as the times swept us up and out. We were the kids carrying this vision inside us and venturing out into neighborhoods, a city that wanted no part of that ideal. And I was a mixed-race girl, trying to make sense of my own family’s troubled past, its terrible darknesses, and the breathtaking currents of the present.

* * *

This is a memoir and history of sorts; a convergence of childhood and politics, since so much of my coming-of-age coincided with the huge swells of change in our country. It is a meditation on what it means to have a mixed identity, forged in post-war, utopian and civil rights ideals–an identity that was sorely tested during the fractious years, when the Vietnam War, civil rights, urban disintegration, and radicalism forced apart any semblance of unity or hope. We were broaching a segregated city that was not ready for us, we the children of the postwar new.

And it is simply the story of an ordinary family, trying, as best they could, to escape the sad demons of their own personal pasts, to make a new life for their children. It is about a strange and paradoxical background: so promising and new, and yet so oppressive and tyrannical.

To tell my childhood is to tell a bigger story—of a certain post-war, post-racial dream incarnated in this community; a belief that we can remake the past to create something new. It is a personal history—with all its vanities, illusions, and self-righteousness–yet it is also a way of looking at our tremulous present. For that tiny little place, that unique upbringing, the events that heaved through my childhood, seeded the cultural and political landscape we currently live in, with all its fractious fault lines. That incandescent bubble connects to the story of the city, the nation have become.

For, while we have once more elected a President who is half-Kenyan, half-American, we are all aware how fragile, how painfully divided our nation. The most significant nugget that emerged from our recent election was the sudden realization that we are a diverse nation—and getting more so. Not just Queens or cities. Our nation grows more—not less—complicated and fraught as we live with the world inside our borders. We are messy, ambiguous, and inter-penetrated—like the mingled enclave that shaped me.

Once again I am twelve, skinny, knobby-kneed, full of inchoate, contradictory yearning, wanting this moment, this community, to last.

It is not so much that history is repeating itself, as that the particular, singular chords of my childhood are now crescendoing, swelling throughout our nation. What was once unique, odd, even vanguard, is now writ large for all of us, decades later.

That is why I return to that soap bubble moment on a warm Parkway night—so fragile, so translucent–holding the past and future aloft. That is why I find myself reconsidering our little triangle of a place, seeking what might be gleaned from those tumultuous and wondrous, yet paradoxical years.

Once again I am twelve, skinny, knobby-kneed, full of inchoate, contradictory yearning, wanting this moment, this community, to last. I want the fourth wall to come toppling down; I want a Hollywood director to emerge out of the tired crowds on Jamaica Avenue and finger me for stardom; I want the glamorous life of books and talk and continents that Parkway so promises. I want, most of all, to understand this dual legacy, darkness and light, freedom and imprisonment.

Before I fold up my chair and follow my mother inside with my half-drunk Tab, I hold here. I drink in this stopped time.

And I return to the sweet, dense promise of everything.