Each of us has a moment, a shiny soap bubble of memory that contains our past and predicts our future.

June 3, 2014

[Editor’s Note: We are excited to present this excerpt from Marina Budhos’ memoir in progress, “The End of Everything,” about growing up in Queens, before it was the culturally diverse borough it is today. The essay will appear in two installments. Part 2 publishes in Open City this Thursday, June 5th.]

Each of us has a moment, a shiny soap bubble of memory that contains our past and predicts our future.

Mine is a Queens summer evening in 1972, the sky rouged a handball pink, for light always lingers in Parkway Village, with the multi-lane Union Turnpike and Grand Central Parkway rushing near. It is one of those nights when I’m desperate to join the glowing circle of grown-up talk, to snatch a last bit of evening magic, of what is possible here, in Parkway Village.

All day, I’ve been hiding out from the muggy heat, stretched out under the throttling chill of the air conditioner, drinking Tab with lemon slices, and making my way through my mother’s paperback books—the racy ones—that are kept in a shelf in the dining room.

Now is the time when I most feel the luminous promise of Parkway, like a planet caught in its peak moment of orbit in the sky.

I am twelve, still nestled in half-childhood; my older brother is gone, somewhere; he is always away. But now is the time when the huge tree in front our porch thrusts its gnarly shade over the courtyard. Now is the time when doors open, voices call out, teenagers start to rove the Green and the playgrounds like summer phantoms, and the neighbors slowly gather on the tiny concrete porches, arranging their folding chairs near the big white pillars, to chat. Accents of all kinds, melodious, off rhythm, clink like an amateur orchestra, twisting into the night air. Now is the time when I most feel the luminous promise of Parkway, like a planet caught in its peak moment of orbit in the sky.

This is stilled perfection. Before my sullen and silent teenage years of bleached jeans and unrelieved hurt. Before the tarnished decline of New York City and the nation, when I use my brand new tape recorder to record Richard Nixon’s resignation on the TV; before the city turns bankrupt, thus ending my mother’s part time job as a college instructor; before another hot summer disco night where my friends and I jam baseball caps on our hair, hoping to avoid Son of Sam, the lone shooter striking down teenage girls. It is before the end of everything, when I know I must leave a waning New York City, my family.

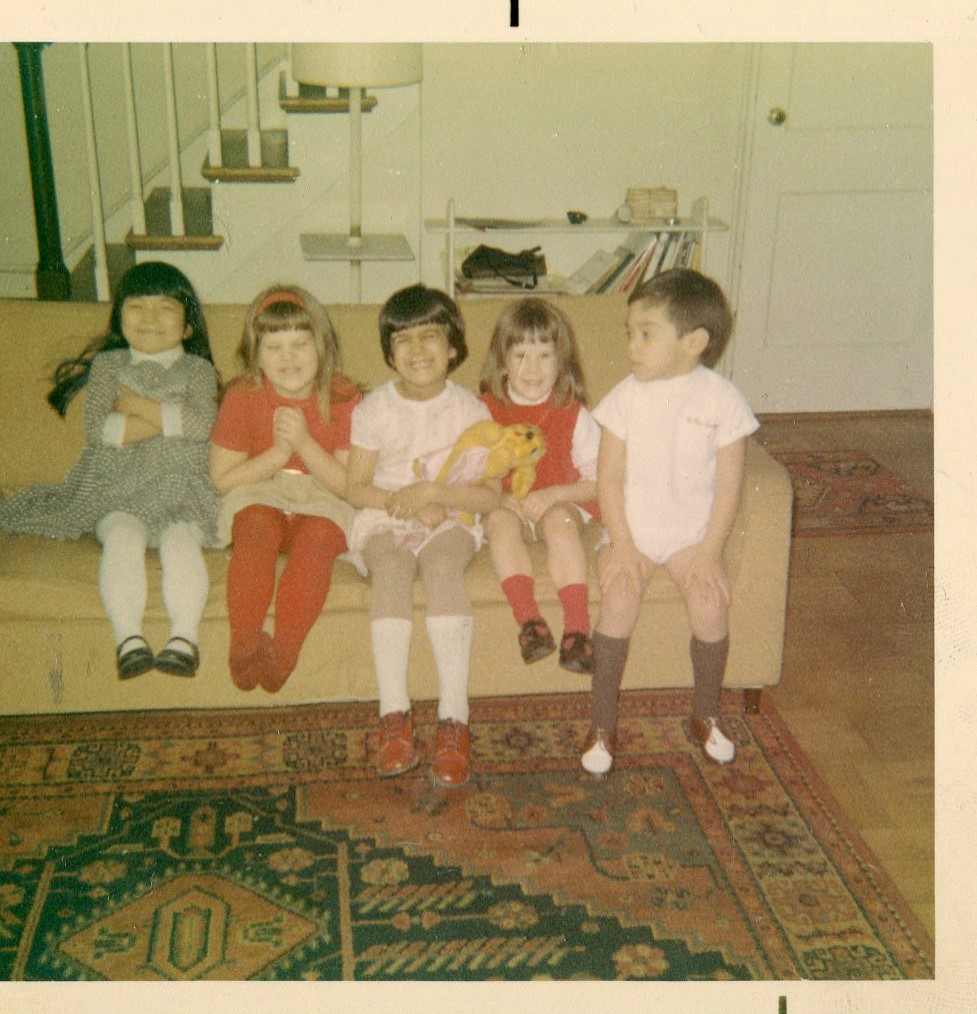

I have lived in Parkway Village since I was little–it is all I really know. It is imprinted on me like a genetic make-up, as deep as my family’s own origins—my mother a rebellious Jewish girl from Brooklyn, my father a dreamy Indian student from the Caribbean.

Over the years, it has become a magnet for a certain kind of family—liberal, international, forward-thinking, or, like me–mixed race, mixed culturally.

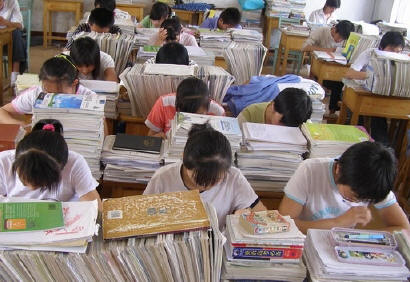

Built after World War II to house U.N. employees, Parkway is a forty-acre enclave of garden apartments, in the middle of Queens, designed like a college campus of inter-connected courtyards and low-slung brick buildings. Over the years, it has become a magnet for a certain kind of family—liberal, international, forward-thinking, or, like me–mixed race, mixed culturally. It is, in a way, a living experiment. Not a hippie commune, but built with the solid bricks of progressive, post-war planning. They have forged a new generation, a new way of being, in us children, that is both unusual and prescient.

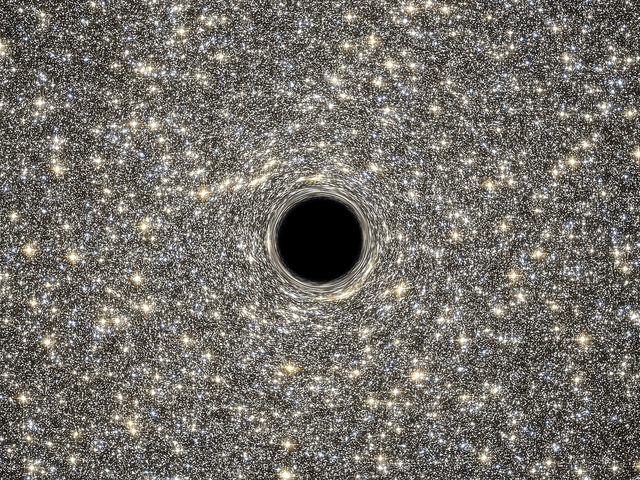

Nearby are the old 1963-4 World’s Fair grounds, whose modular buildings loom over my childhood with silvery, mythical force. The Unisphere, a giant steel-girded globe, always seems tilted over us, casting its shimmering, mammoth shadow, urging us toward a new, space age future. It adds to the sense that we are the center of the world; that in fact, the world came to us, other countries, continents lapping at our doors.

There’s a phrase, Hey, are you a Parkway kid? Or, I knew her, She was a Parkway kid. Everyone knows what you mean. We carry, in our slender limbs, an easy sense of fairness, of taking for granted this hopeful mixing. What might be separate or strange or exotic out there, in other neighborhoods, was simply regular, for us. And there is a sense of safety too—at each end of the complex stands concrete pillars, demarcating that you are entering a different, protected space. Inside we are safe, reassured by the pattern of interlocking brick buildings, a sameness that has gathered us all together, united such disparate families.

Quick, quick, before the night is gone—hurriedly I fill up another glass with Tab, drop in a lemon quarter in a chunky, amber-colored glass, find the last of our plastic-webbed lounge chairs folded into the hall closet, and scoot over to be close to the grown-ups, covering my bare legs with one of my mother’s crocheted afghans.

I fill up another glass with Tab, drop in a lemon quarter in a chunky, amber-colored glass, find the last of our plastic-webbed lounge chairs folded into the hall closet, and scoot over to be close to the grown-ups…

A deep, shivery pleasure courses through me. I wear my new red hot pants, my cotton print halter top that my mother has made from tablecloth fabric. Now I can be part of the stimulating, warming circle of adult talk. Parkway talk—about everything and nothing—world politics, neighbor gossip.

Through the shrubbery, I can hear the sound of cars, engines ticking warmly as someone walks away, to another courtyard. Other conversations tinkle upward from the patios, in the back. The large tree sheds burgundy pods, resembling dried chili peppers, and I love to scoop up crackling mounds into my hands. I can just make out their dense sap smell; it is somehow part of the richness of this moment.

I’ve grown up with this adult Parkway talk my whole life, voices from other continents, spilling at the edges of my childhood. My favorite nights are when my parents have company over, and I am deep under the quilt, lulled to sleep by the waves of laughter that pour up through the thick, waffle-patterned ceiling that all the Parkway apartments have. Their conversation always sounds so interesting, so rich! Now I’m at that cusp moment when I too can come into the circle of their talk, smile out from the rough afghan, say a thing or two, and join the tinkling sounds.

With us on the porch are the Farghals, from Egypt. Abla is tall, fair-skinned with an round, open face; her husband Mahmoud is a studious intellectual, with a slightly pampered air, who is working for the Arab League.

I am the good daughter, who is especially at home in all kinds of houses, all milieus. It is as if I have absorbed Parkway’s credo so thoroughly, it has become my bones, my skin.

They have become like family to us, and we will inherit some of their furniture when they leave for their next posting—the orange leather hassock, the gold rimmed cups that they used for their thick black coffee. I babysit for their son, who is deaf. When they moved to a new, larger apartment on the other end of the courtyard, they brought in a servant, Fatima, who sleeps under the dining room table and learns English from watching soaps on television.

Afternoons she confides in me: how the Farghals will send her back to be married to some terrible man who will beat her. Suddenly Egypt’s alleys swing open for me. This is what I love, this confiding, these dense, winding secrets and soon I am proffering advice and comfort. I am the good daughter, who is especially at home in all kinds of houses, all milieus. It is as if I have absorbed Parkway’s credo so thoroughly, it has become my bones, my skin. It is who I blissfully am. The experiment has worked.

In their old apartment below there now lives a young actor—Tony Danza, with his nurse wife—and I have also begun to babysit for his son. I’m a dreamy, serious girl and have confessed that I might want to be an actress, and so he sat cross-legged from me, and explained the fourth wall in acting. I leave this babysitting job with my dollar bills tucked in my jeans, cheeks hot, dizzy. I am thrilled, but a bit scared by his burning eyes, the way his hands waved within inches of my face.

There are also the Goldbergs, who have brought their chairs. He is a musician from South Africa, a slight man with a twangy accent. I have a tiny crush on him—I am always drawn to slight, foreign men with a bit of intensity. They are the ones I can talk to, I am convinced they are the ones who will understand me, light up my own vivid, inner life. I babysit for their two sons, as I do for just about all the kids around. He will play with Paul Simon’s Graceland album, and be part of the burgeoning music scene that brings South African music to the world. His wife Helene is American and she has gap-toothed smile. My mother will eventually clash with her, but tonight, we are all gathered together, getting along in a jolly, friendly way. Laughter rolls all around.

Tonight Helene is talking about their recent trip to South Africa; how she loved to sit on the hotel verandah and see the spectacular view. “What a beautiful city,” she murmurs. “I could hang out at that hotel all day!”

I am always drawn to slight, foreign men with a bit of intensity. They are the ones I can talk to, I am convinced they are the ones who will understand me…

This evokes Abla’s reminiscences of the beaches in Alexandra, where she grew up. Sitting there, in the dim night, the tree’s blackened shadow spread over us, I can imagine each place, as familiar as our own drive to Jones Beach. Off to the side Mahmoud now and then murmurs about his graduate studies dissertation on the Koran and the modern state.

Can one want a moment, an age, to last? Ever since I was very young I have tried to make time stand still. There, I would stay, fixated on the swirling particles in the air. There. Stop. But it never works. The instant I seize on this thought, I know I am looking backwards and time slithers away, mercury-like, in my palm.

The man across the way is dying of lung cancer. I know this because I see him every day haunting our courtyard, growing gaunt, as if slowly turning to bone, disappearing from this earth. All through the fall and the winter, as the dry leaves turned on the ground, I obsessed about him, for this is the first time I’m aware of death, wondering to where these spinning particles ultimately drive. I rebel against this adamantly. I refuse this hotly, my almost-teenage body full of hurt and fear.

What will become of me—of this whole place?

[Summer Nights, Part 2 will appear on Open City this Thursday, June 5.]