Malayalam, English, Arabic, French: Meena Alexander inhabited all these languages, reminding her of the many homes she had lived in and experienced.

May 9, 2019

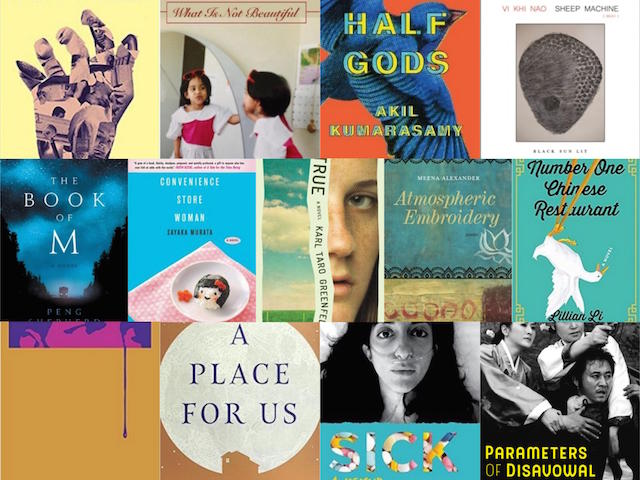

The following is part of a series of essays and reflections published on The Margins in remembrance of the life and work of poet and scholar Meena Alexander, who passed away on November 21, 2018.

Meena burrowed into her words; she consumed them, generated them, wore them, chiseled them, wrestled with them and carved them into the shapes she desired to convey the joys and sorrows of those whose lives she encountered. “Alphabets of Flesh” is the title of a poem from 1996. When I first read those words, I was struck by the force of the articulation that conveyed the wrenching labor of pulling words from the bone and muscle of the body. Writing, for Meena, was entangled with both pain and relief; it was a necessarily difficult process, because, it seemed to me, she felt that writing should not be easy. Language only matters when what we say has come from struggle and the pull and pulsing of trial. She summons the “ferocious alphabets of flesh/ [to] splinter and raze my page.”

Meena says about “Alphabets of Flesh” that writing the poem was hard because “perhaps because of the muteness and illiteracy at the end, allowing me to identify with what is dumb and bleeding.” Out of muteness comes language; out of wordlessness comes words—these paradoxes of expression abound in Meena’s poetry; she understood that to be a poet, to be a writer, was both a gift and a curse. A gift, because you were close to the sacredness of sound, the many utterances that she was surrounded by—Malayalam, English, Arabic, French. She inhabited all these languages, reminding her of the many homes she had lived in and experienced. Writing was the gift that allowed her to rope in all these disparate sounds and concatenate them into feeling, recognition, understanding. She could be melancholic, joyous, suffused with energy, weary, and robust all at the same time in the lines she stitched, the burning embers of her speech, the salve of her utterance. And the curse of writing—she was fated to feel deeply the anguish and suffering of those about whom she wrote, drawing the words from within her, digging through the rich soil of her consciousness. Meena’s heart reverberated with the grief of others. There is a profound earnestness to her writing.

In Illiterate Heart (2002), she writes: “What beats in my heart? Who can tell?/ I cannot tease my writing hand around/ that burnt hole of sense, figure out the/ quickstep of syllables.” What a delightful image we have–the agile movement of syllables, the “quickstep”—a choreographed skip. She gestures to the playfulness of language and creates avatars of words as “Letters gr[o]w fins and tails/ Swords spr[i]ng from the hips of consonants.” Language is embodied, language is substance and materiality, language is motion. But always in her writing language is also stasis; amidst the burning fires, the rushing waters, she creates perfectly constructed spaces of contemplation, absorption, and deep meditation.

I envision Meena made up of alphabets, letters caressing the contours of her body, defining the outline of her being, pouring into and out of her heart, bubbling from the depths of her consciousness. When she recited her poetry or read from her essays, she enunciated her words carefully, as though she wished to bless them and thank them before they left her mouth. Speaking was not simply an act of sharing knowledge or delivering a message. Speaking was a baring of the soul and an invitation to join hands and hearts in solidarity.

In one of her last poems, “Refuge,” she writes, “I have kissed the eyes of the child / Who fell off the fishing boat / Who barely floated, who swallowed / Sand and could not breathe.” Meena’s fiercely empathetic sensibility made it impossible for her to write without embracing the tumult of the world. She thrust herself into the wrenching pain of a parent’s loss and a city’s despair; she decried a nation’s arrogant rage. Through her language, with alphabets “stripped to skin and ligament,” she fervently desired that we could sear ourselves into each other’s traumas. For only then could we awaken to the urgency of ending them.