夜來沉醉卸妝遲 || With night you sink drunk slow to undo/ your hair

March 13, 2019

The following ci by Li Qingzhao, with translation and note by Jenn Marie Nunes, is the fourth installment in The Pronoun folio of the Transpacific Literary Project. Find the rest of the folio here.

A selection of ci by Li Qingzhao

translated by Jenn Marie Nunes

如夢令

常記溪亭日暮

沉醉不知歸路

興盡晚回舟

誤入藕花深處

爭渡爭渡

驚起一灘鷗鷺

To the tune, Ru meng ling

You often remember the river pavilion dusk

So drunk you don’t know the way back

Tired of the evening your boat returns

Mistakenly deep into a patch of lotus

Paddlingpaddling

You startle a shoreful of herons to flight

如夢令

昨夜雨疏風驟

濃睡不消殘酒

試問捲簾人

卻道海棠依舊

知否知否後

應是綠肥紅瘦

To the tune, Ru meng ling

Last night a spattering rain, sudden wind

Deep sleep didn’t quite clear your head of

wine

You try to ask the maid rolling up the blinds

But she says: the crabapple’s just like before

Doesn’t she know?Doesn’t she know?

It should be: the green fat, red thin

武陵春

風住塵香花已盡

日晚倦梳頭

物是人非事事休

欲語淚先流

聞說雙溪春尚好

也擬泛輕舟

只恐雙溪舴艋舟

載不動許多愁

To the tune, Wuling chun

Wind settles, dust carries the scent of flowers

all used up

Day goes late and you’re too tired to comb

your hair

Everything is here but the one who matters,

so what matters

Wanting words, tears flow

You’ve heard Twin Creek’s still sweet with

spring

And think you’ll float out in a little boat

Only you’re afraid Twin Creek’s little

grasshopper boats

Cannot carry such a load of grief

訴衷情

夜來沉醉卸妝遲

梅萼插殘枝

酒醒熏破春睡

夢斷不成歸

人悄悄

月依依

翠簾垂

更挪殘蕊

更拈馀香

更得些時

To the tune, Su zhongqing

With night you sink drunk slow to undo

your hair

Bits of plum blossom trapped to branches

Then dredged out of spring sleep by stale wine

fumes

Dream snapped off so there’s no slipping

back

The house so so quiet

The moon lingers close

You draw the kingfisher-green blinds

Again, you roll the buds between your

fingers

Again, you finger their fading scent

Again, you grasp a little time

from the translator

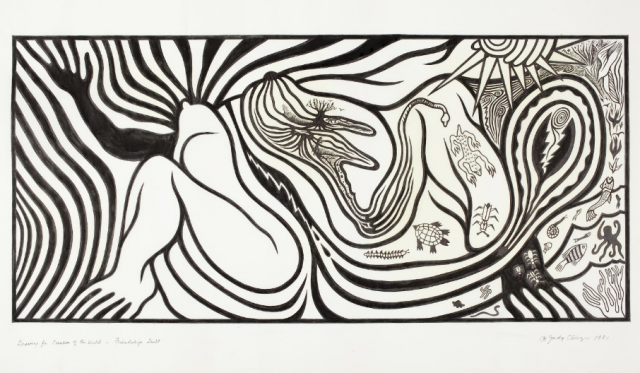

Honored as “China’s greatest woman poet,” the only Classical Chinese poet who is both a woman and has gained the status of being “known to all”, Song Dynasty poet Li Qingzhao’s writing seems to have always been read through the lens of gender. Moreover, Li has been mythologized in Chinese historical memory not just as a poet or even as an exceptional woman poet, but as one half of a great romance through her marriage to scholar-official Zhao Mingcheng (1081-1129), who shared her love of literature. This mythologizing of Li Qingzhao’s (love) life is partly the result of autobiographical readings of her ci or “song lyrics”, even though the ci genre—evolved from popular songs to be performed in banquet halls or entertainment quarters—was largely built on the persona poem of men writing poems with women speakers. The speaker in Li’s poems has consistently been conflated with Li herself, which has meant that her ci have generally been translated into English using the first person “I,” or occasionally the third person “she,” despite no subject being marked at all in the original Chinese. As Ronald Egan points out in “The Burden of Female Talent: The Poet Li Qingzhao and Her History in China, among other things, this move denies that Li as a woman has the skill or imagination to write beyond the limits of her personal experience.

One possibility would be to translate Li’s ci, and by extension much of Classical Chinese poetry, without a subject pronoun at all. While I am interested in pursuing this mode of translation, and even putting aside the fact that the lack of a subject pronoun in Classical Chinese does not necessarily mean a particular subject is not implied, I think it is difficult to place the English speaking reader in these poems when there is no subject. Without subject pronouns in English, verbs dissipate into the gerund form or force an overwrought phrase, such as “So drunk not knowing the way back”; or “So drunk as to not know the way back.” For me, Li Qingzhao’s poems—with imagery that is both vivid and present—feel like places one is meant to inhabit rather than watch pass by. And so, instead of “I” or “she,” my translations argue for use of the second person, making “you” the subject. I believe “you” can return Li’s poetry to the place of poetry (rather than historical or autobiographical document) while still retaining the uniqueness of her voice as it is, in this genre, enmeshed with a sense of intimacy. “You” can create some distance between the speaker and the author, which, even if read as a sort of “self-talk,” instills a sense of multiplicity or disunity in the voice and locates a potential multiplicity in the speaker-poet’s subjectivity. At the same time, since “you” can also be read as direct address to an audience, or in this case “the reader,” it still draws you into a relationship with the speaker—akin to how the first person has the potential to place you “inside” the subjectivity of a poem. “You” allows Li’s ci to do more than stand as gendered production of historical “facts” while drawing contemporary readers into the intimate space of the poem.

My translations of Li Qingzhao’s poetry attempt to engage an ethical reading practice, albeit in a subtle way, exploring a queer-feminist mode of translation and questioning the gendered construction of Li and her poetry. How have the notions of “woman” and of subjectivity traveled over time, both in a Chinese and an English speaking context? What does the use of “I” or “she” in English, with their various baggage of exceptional individuality or oppressive binaries, do to Li Qingzhao’s poetry? What can “you,” as an intimate gesture toward another, even another within the self, perhaps allow us to see or feel in the poems?

Because part of my queer-feminist approach is a call for an ecology of translation, where I hope to queer the notion of the authoritative translator and the authoritative translation in order to open up space for a range of approaches to any one text, I would like to acknowledge the previous translators of Li Qingzhao’s ci whose work I have spent a good deal of time with: Ronald Egan, Eugene Eoyang, and Jiaosheng Wang; and the professors who have made space for me to explore Li’s poetry: Patricia Sieber and Meow Hui Goh.