A Conversation with Albert “Prodigy” Johnson, Queens Author and Rapper

I’m only nineteen but my mind is older/when things get for real my warm heart turns colder

–Prodigy of Mobb Deep, “Shook Ones (Part II)”

In 1994, the rap duo Mobb Deep released a song heralding their arrival on the New York scene: Shook Ones (Part II). Chilling and spellbinding, the song begins with a cacophony of sirens, and gives way to a loping, melancholic piano loop as Albert “Prodigy” Johnson and Kejuan “Havoc” Muchita—then teenagers—intone gravely. Their sound, violent and vulnerable, began a new aesthetic in hip-hop, and their subsequent albums helped bring the borough of Queens back to the national stage. In 2012, Rolling Stone named Shook Ones (Part II) one of the top fifty rap songs of all time.

Queens produced many rap stars in the eighties: Run D.M.C. and LL Cool J came from Hollis; Roxanne Shante, Kool G. Rap and MC Shan grew up in the Queensbridge Housing Projects. A 1986 battle with Bronx-based Boogie Down Productions left the borough wounded; for several years afterwards it seemed that the rap zeitgeist had left Queens.

Then, in the mid-nineties, several albums from Mobb Deep— including The Infamous (1995) and Hell On Earth (1996), both of which went gold—and new music by Nas and Capone-N-Noreaga, brought renewed attention and a measure of redemption to the forgotten borough.

Albert Johnson’s successes in music might have been predicted. His paternal grandmother was a dance choreographer who worked with Ben Vereen and taught the children of Diana Ross. His parents were musicians; his mother, Fatima Johnson, sang in the sixties vocal trio The Crystals. She was from a southern family of some repute: her great grandfather was William Jefferson White, the founder of Moorehouse College.

But, Johnson faced many challenges. As a child stricken by sickle cell, he often missed school. His father, addicted to heroin, soon left the family. Without his father, and paralyzed by pain– and painkillers–he became depressed. He dropped out of school in the ninth grade and moved to the unstable but storied Queensbridge Housing Projects to stay with Havoc, whom he befriended during his first and only year in high school.

His dark view of the world, shaped by his depression and the violence of Queensbridge, did not leave him after his successes. In 2008, at the age of 33, he was arrested for gun possession, and sentenced to three-years in prison. It was there he began a creative transformation.

Prodigy’s lyrics, while vivid and violent (“I’ll stab your brain with your nosebone,” he warns on “Shook Ones, Pt. II”) were also psychologically complex, revealing regret and, on occasion, hope. “I spent too many nights sniffing coke/ getting right/ wasting my life/ now I’m trying to make things right…do things for the kids,” Prodigy confesses on the 1999 hit “Quiet Storm.”

His dark view of the world, shaped by his depression and the violence of Queensbridge, did not leave him after his successes. In 2008, at the age of 33, he was arrested for gun possession, and sentenced to three-years in prison. It was there he began a creative transformation.

My Infamous Life (his memoir edited by Laura Checkoway) was crafted while he was incarcerated. It was published by Touchstone/Simon & Schuster upon his release in 2011 and was both hailed (and critiqued) for its frankness. Hua Hsu wrote that the audiobook might be “the best rap album of the year.”

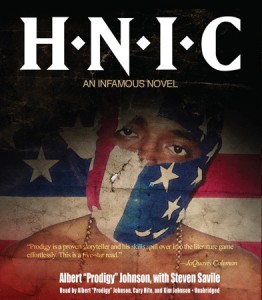

Prodigy has now turned to fiction. Last month he released a novella, H.N.I.C., via a new imprint deal with the independent Brooklyn-based press Akashic Books. While the protagonists of this tale of robbery-and-redemption are from Bedford Stuyvesant, Prodigy maintains strong links in Queens, often recording at his studio in South Ozone Park. We caught up with him in his Manhattan studio, where he was reviewing old Mobb Deep masters. He spoke about his favorite reads, the process of writing, and growing up in Queens.

You left school early on. What were some of the readings you did on your own that made an impact?

My mother gave [me] The Autobiography of Malcolm X as a teenager. I read the whole book. It had a great effect on me. He started out as a gangster, a stick up kid, and then… his transformation. I could relate. It made me want to learn more about my culture, and other cultures. I started to progress from there. After that I remember my man gave me a xeroxed copy of the Supreme 120 Lessons: for the Nations of Gods and Earths…and I went home and read the whole thing. But it was the writing of Dr. Malachi York put everything into perspective for me. It’s very spread out–a lot to digest. I started reading his work when I was sixteen, and it took me until I was 29 or 30 to grasp it.

The conscious rap movement of the late eighties, with BDP, Rakim and Public Enemy placed a heavy emphasis on reading, did that affect you?

I listened to all those dudes: Boogie Down Productions, Rakim, Public Enemy. X-Clan was a major influence. Shout out to X-Clan. They don’t get acknowledged enough.

Are there any books that you’ve read recently that might surprise people?

Hmm. Maybe The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Due to the disease [sickle cell], I’ve become very interested in reading about food.

What are some of the challenges and opportunities that writing books, and especially fiction, present for a rap artist?

Literature is for a different audience. Like, even if you use slang you have to explain it. Laura [Checkoway] taught me that. Fiction is more universal in a sense. I got a crazy imagination and fiction allows me to step outside myself.

Is it fair to say that the depiction of Tanya (the main female character in H.N.I.C.) is more sympathetic than those of women that appear in Mobb Deep music?

Fiction definitely helps to think outside the box. Music, I try to keep it a certain way. In fiction, I can build and elaborate on the characters more.

In this excerpted audio book, Albert “Prodigy” Johnson reads the first chapter of his novella, H.N.I.C.

You wrote in your memoir that when your father died he was working for IBM, and you also recount a story of watching him rob a store. In H.N.I.C., the main character, Pappy, is a computer whiz who wants to get out of the robbery game. Is he based on your father?

Wow. It’s great that you said that. I had never thought of that until you just mentioned it. But no, not consciously.

Addiction is a theme that runs throughout the book. Was that something you set out to explore?

The addiction side I definitely put in on purpose; I wanted to show that part of the game. My pops was addicted to heroin, and I was addicted to painkillers for my sickle cell. Also in the movie Gridlock, with Tupac, they had major characters who were heroin addicts, and I thought, I want to try that.

The Queens’ neighborhoods of South Jamaica, Lefrak and Queensbridge all play major roles in your memoir. These African-American enclaves in New York are separated by some geographic distance. Can you talk about how you see these communities being connected?

Well, on the gangster side—the people that are in the streets—pretty much everyone knows everybody else in the game. Otherwise there are coincidences: Like I was born in Hempstead, and Havoc is from Queensbridge, but both of our grandmothers lived in Ravenswood Houses.

You recently accompanied Chef Eddie Huang to a high-end Korean restaurant he was reviewing. He notes your favorite restaurant was Soho’s Woo Lae Oak. Did growing up in Queens with all its diversity impact you and your tastes?

Queens affected me in many ways. Like, I can understand Jamaican patois—we’d always hear the old school West Indian music playing growing up. Plus my grandmother Bernice Johnson was a successful black woman—one of the first to own her own building, a dance studio, on Jamaica Avenue. After her shows she took us to different kinds of restaurants. I even tried caviar. So I grew up on both sides of the track and know how to interact with people from different backgrounds. Not all of my people are like that.

You’ve embraced “new New York” rap artists, like Action Bronson, from Astoria, and Roc Marciano, from Hempstead, both of whom you recorded with on your new solo album Albert Einstein. You rarely collaborate with other artists. Why the recent change?

I went through a self-transformation in jail. I used to be very opinionated. I still feel that way, but my opinions won’t be so disrespectful. I was locked up with this young kid named Fresh from Poughkeepsie. We watched 106 & Park together (I never watched that when I was out, but there was nothing else in there to do except exercise) and I used to critique all the artists on there. Fresh said, “you gotta give people a chance, P! They are trying to eat just like you.” I thought about it and said, “you right, son.” I’ve changed. I’m more open.

On the other hand, several older Queens rappers that you were associated with have taken to YouTube or records to malign you. How do you deal with those incidents?

Every circumstance is different. One person I could forgive and another not. I’ve apologized too. When I came home from jail I called a number of rappers to clarify things I had said.

What are some of your favorite neighborhoods in Queens that people might not expect?

Hmm. Well around the [South Ozone Park] studio we sometimes hit the Trini and Guyanese clubs…. You might see me at Moka NYC, in Richmond Hill, chilling out with some reggae artists.