Here are some tips from a Chinese American New Yorker who went to Toisan, China to trace their parents’ roots.

July 3, 2018

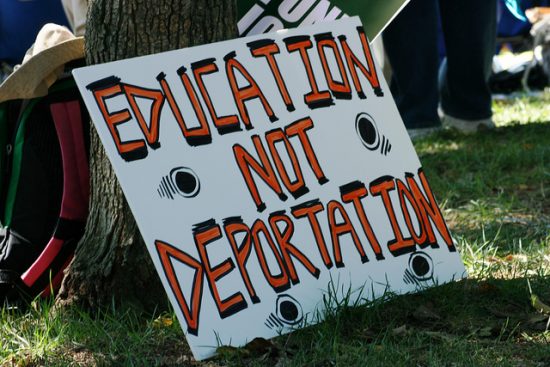

In kindergarten, the white kids made fun of me for bringing my dad’s stir-fry noodles to lunch. Slurs of ching-chong were regularly hurled my way. I learned how to throw away home-cooked food earlier than I learned how to multiply. In high school, the Chinese Exclusion Act was half a sentence in my American History textbook. By the time I got to college, I fought for an independent ethnic studies major because I wanted to be in control of my own education.

Growing up in New York City in the midst of that, my grandparents nourished me in ways I never found in school. My grandmother sculpted wu gen hang乌勤藤 sweets made from the flour of dried plant leaves on Chinese holidays and my grandfather sang Toisanese songs each morning he walked my sister and I to the bus stop. They raised me to learn more about the history and resilience in my lineage than the dozens of teachers in my 13 years of schooling ever taught me. And they fortified my tongue with our language.

“The intimacy created in the walls of my living room extended its blanket to the rest of the city. Everyone became family and the secret I had cultivated at home ran from my grasp and multiplied.”

When I graduated college, I was awarded a fellowship to travel for one year to Chinatowns in eight countries around the world and document stories of migration and resilience across the diaspora. This project was self-created and stemmed from the ways Chinatown was a steady second home in my life. From listening to elderly musicians strum erhus in Columbus Park to reciting ancient poems for the Mid-Autumn Festival in Sunday Chinese classes, I found a home in the community the diaspora created. Yet, I always had deeper questions about where the rest of my ancestors were from beyond New York.

“When I was young in the village,” my mother said, leaning forward in the kitchen chair at our home in Brooklyn one evening, “every day, I would call the chickens back home. They walked around all day on their own outside.”

She put down her phone and cupped her hands around her mouth. “I would stand on my tip toes and call ‘ji jiii, ji jiiiii!’ And they would come running back.”

I could see my mother in her preteens, sleek black hair bobbed just above her shoulders, standing at the doorstep of their cement house. The sun had just set underneath the horizon and the sky glowed dark blue. She closed the door behind her and looked up to see her mother walking home.

What did her surroundings look like?

I had been to Toisan once when I was six years old, but lost recollection of the place afterwards. My imagination was limited because everything about my family’s past was out of my scope of understanding. I couldn’t imagine the kitchens, the streets, the atmospheres that I heard about in passing. I needed to see life there.

In Chinese, there is a word – 寻根 cam gan, meaning to be in search of roots. My best guess is that because so many of us, specifically from the Guangdong Province, are in countries across the world, returning to learn about our roots was so common it became a phrase. There’s also a strong sense of homeland within the culture. Many Chinese overseas, for example, wanted their remains sent back to China after they died. Other immigrants return home to pay their respects to their ancestors once a year during Qingming, or the Tomb-Sweeping Festival. Chinese cemeteries and gravestones list the exact province, city, and village the person was from.

In March of last year, I traveled back to Toisan alone, carrying a 3×5 notebook with the names of each of my grandparents’ villages and their names written in Chinese with English phonetic pronunciations. Here is a snippet of my journey to trace my family roots, written for those also in search of lineages.

1. Begin by gathering as much information as possible about the villages and family members’ names before the trip. Every piece of information, especially in Chinese, is crucial.

During family gatherings in living rooms and restaurants in the months before the trip, I started compiling the names of my family members and their villages in what became my roots search notebook. My family immigrated in the 1980s and I am the first generation born in New York. But over 35 years have passed since they lived in the village. Each of them has gone back a handful of times, but memories also became more muddled with the decades.

My questions of “What year did you immigrate?”; “Who is still in the village?”; “Where is the house located?” were met with “Why do you want to know?”; “It was so long ago, I don’t remember.” My family rarely talks about the past. But when they do, the stories trickle out in between sipping soup from the ladle and walking home together. They do not happen when and if a camera or voice recorder is placed at the table. Words, then, are what I have to capture these moments.

From my family, I learned that village houses don’t have door numbers, but that my maternal grandmother’s house was “next to the village well” and that my paternal grandfather’s was “next to the water bank.” With different relatives, I managed to reach as far back as writing down my great-grandparents’ names, which was important because the village elders would be more likely to remember the older relatives’ names.

“I didn’t know how I would fare living in China, gendered as woman and traveling alone, and how far my Chinese would carry me.”

Although China’s official language is Mandarin, many villages speak their regional dialect, which is often mutually unintelligible. In Toisan, Toisanese is standard. When I arrived in the main city of Toisan, suddenly the language I only ever spoke at home and in Chinatown’s bakeries became norm. The intimacy created in the walls of my living room extended its blanket to the rest of the city. Everyone became family and the secret I had cultivated at home ran from my grasp and multiplied. Although I couldn’t talk politics and history as fluently as I could food, in the villages I was still able to repeat voice-recorded oral pronunciations of people’s names. Village names ended up giving me a clear destination even if I had no idea how to get there, and my own tongue blossomed with time.

2. Elders are key.

“But when you get to the village, how do you find their house and distant relatives?” I asked Albert Cheng and Steve Owyang at a Friends of Roots meeting in San Francisco. Their program took Chinese Americans back to their ancestral villages. After introducing myself and happening to be in California at the same time, I went to meet them, not fully understanding how to uncover the details.

“The elders,” Al said. “Once you get to the village, look for the eldest person there and ask if they remember the family.” Sometimes, with enough family members’ names, you could hit the jackpot and the answer would be yes. It was a game of well-calculated luck.

When I arrived in my paternal grandfather’s village, I did exactly that. My mother’s classmate put me in contact with her father who still lived in Toisan and agreed to accompany me to the villages. We passed the village gates and started looking for an elderly villager to ask if they knew my paternal grandfather. The first grandfather donned a gray beret and light-blue striped short-sleeve button-down. He told us, “I’m not from here.”

But he called to another uncle who he knew was from the village. The second uncle was riding his bicycle into the village. “Do you know who Yik Chan is?” I asked him. “He’s my yeye 爺爺.”

Resting one foot on the ground, the second uncle said, “I don’t recognize his name, but give me a moment. I’ll call someone who might.”

He got off the phone. “Head to the water bank,” he told us with a voice eager and hopeful. “They’ll be waiting for you there.”

The water bank was where my grandmother told me the house was. In village tradition, families live in the same houses generation to generation, which is why the elders know who lives where. It turned out that my family had very distant relatives – the last two – who were still living in the village and took care of the house after my grandpa and his siblings had left. When I met them at the water bank, I learned our ancestral home was still there. They started to tell me about my grandfather’s past.

3. Keep a list of people who can support you. Remember you are traveling solo but you are not alone.

On the two-hour bus ride from Guangzhou to the main city of Toisan, I nervously sat in my seat, headphones in, unsure if the names and research would lead me anywhere. I didn’t know how I would fare living in China, gendered as woman and traveling alone, and how far my Chinese would carry me. As the city skyline melded into expanses of green, I opened my notebook to the page where I kept a list of names of people who supported me. A list of close friends, mentors, and friends of friends in the diaspora who had also gone back to China hovered on the page. I exhaled — the isolation that comes with solo traveling momentarily subsided.

4. Find resources and institutions in the villages, especially try to locate ancestral halls and zupus 族谱.

In a lot of places in China, and specifically the Guangdong Province, there are ancestral halls based on surnames, e.g., Chen, that hold the clan’s history and records. These records may include books that trace the surname to the first ancestor or a list of all the villages in the region that share the same surname.

Sometimes, the ancestral halls or village offices also have zupus 族谱, which are genealogy books that list every generation of a family member as far back as was documented. Genealogists in the village would go door-to-door and record family members’ names from the current generation to the previous ones. These zupus can answer a lot about family trees. However, not every village has a zupu, depending on whether there ever was the initiative and funds to make the books for the village. Other times, the zupus have not been kept up to date after immigration.

I got off the bus in Kaiping 開平, the county next to Toisan where my paternal grandmother is. My grandparents lived here for years after they got married. I learned that the Guans, my grandmother’s maiden name, had a library in the main city, Chikan 赤坎, in Kaiping. In my second visit, the Guan library was finally open. I had heard there was a Guan zupu and I was prepared to go back to the library until I found it.

I entered the open hall of the library, calligraphy phrases and framed portraits decorated the walls. An elderly man with black-rimmed glasses wearing a gray suit took me to the office where the genealogists were. He introduced me to Mr. Guan who upon hearing my story said, “I wrote the Guan zupu. We’re working on the third edition now. What is your great grandfather’s name?”

I repeated the phoneticized Chinese I rehearsed and showed him the characters. He opened a large red book and began flipping the pages. After reading the table of contents, the Chinese barely decipherable to me, he flipped through the pages and stopped at page 1112. He moved his fingers down the vertical lines.

“Here he is.” My heart beat fast. He found my great-grandfather’s name.

He continued to move down to my grandma’s generation. A pause.

“It looks like her name isn’t here,” the man explained to me. He read her brother’s names.

“Only the names of sons are recorded?” I asked him, a lump began to lodge itself in my throat.

“Yes,” he smiled, almost apologetically.

My grandmother, born girl, did not matter in history. It turned out zupus only recorded the names of sons since daughters do not carry the last name when they marry. Wives were listed by last name, if mentioned at all. I closed the zupu, seething.

5. Give yourself time and flexibility for changes and new leads.

“Your great-grandfather went to Myanmar to work for years,” a village grandmother told me outside of my grandma’s house.

“He barely escaped back to China,” another villager added, “And came back with nothing but tiger balm to his name!”

They erupted into laughter. We were standing outside my maternal grandmother’s village where she was born. My month in Toisan, without much planned, allowed me to follow leads and go from village to village. I looked up at the fortified solid gray brick house behind them. “This was where grandma was born,” I thought.

“Her grandfather went to America and sent money back to build this house,” a grandmother told me. I never knew that we had relatives that many generations back who stepped foot in America. The details in village memory were clearer than in my family’s.

“As the first generation born in this country, I am technically not that far removed from knowing my lineage. But that ‘knowing’ is measured by number of generations.”

What originally started with one goal of visiting a village in China led me on a month’s expedition for my roots quest. Stories of distant relatives first going to Latin America and Southeast Asia had remained in collective village memory and never left. I learned who my grandparents were as children and growing up as adults my age.

6. Start somewhere.

“The difference between you and me,” my friend Rodrigo, a fourth-generation Chinese Peruvian said to me one night during my travels, “is that you can ask your parents what villages they’re from and they may have a hard time remembering, but there’s a way you can find out. For me, it’s all lost.”

When I traveled to the Chinatowns in Lima, Peru, and Havana, Cuba, the months before I went to China, I met second- to fifth-generation Chinese descendants who wanted just as badly to know Home. Some were elderly multi-racial Chinese Cuban descendants whose parents were no longer living to answer questions they had. Others were fourth-generation Chinese Peruvian youth who tried to salvage connections lost over the generations.

Meeting them made my trip all the more urgent. It mattered even more. As the first generation born in this country, I am technically not that far removed from knowing my lineage. But that ‘knowing’ is measured by number of generations. Had I not made this trip back to Toisan and lived there, I don’t know when, if, and how I would have uncovered so much.

“My trip was the culmination of many oral history attempts with family members. I had to face that by the end, not everything was answered.”

Already in my community of young Chinese Americans, it’s getting rarer to be able to speak our home dialects. I’ve seen how languages and customs begin to fade, but from meeting so many others in the global diaspora, I’ve also seen how Chinese culture shouldn’t be held to pure standards and singular definitions of who does and doesn’t get to be a part of it. I saw on a global level how “Chinese-ness” was defined by traits such as fluency in the language or ability to use chopsticks, but left out multi-racial Chinese Cubans, for example, who led preservation efforts of Havana’s Chinatown.

7. Remember that you are trying your best. It unfolds slowly and there is more to come.

My trip was the culmination of many oral history attempts with family members. I had to face that by the end, not everything was answered. In some ways, I left with even more questions. Women, like my grandmothers, were not documented in the zupus. Who else in my lineage will we never get to learn about? What about the queer and trans ancestors who never had children? What do I do as the elders are aging? Where are the rest of the zupus?

Today, my imagination and comprehension of our collective past has expanded. I left Toisan able to know my grandparents as children and to set foot in the houses where they were born. I now know how to take the 45-minute bus ride from Toisan’s main city to the town. I know how to bargain with the motorcycle drivers to get me from the town to the village. I know our city as more than just a color-coded area on the map of a country.

I met grandmothers who knew mine when they were young. I found photographs before they faded from the sun after my family left for the U.S. I am more deeply grounded in who I am because I know more about who and where I come from, more than I previously did when I only knew my family in the context of America.