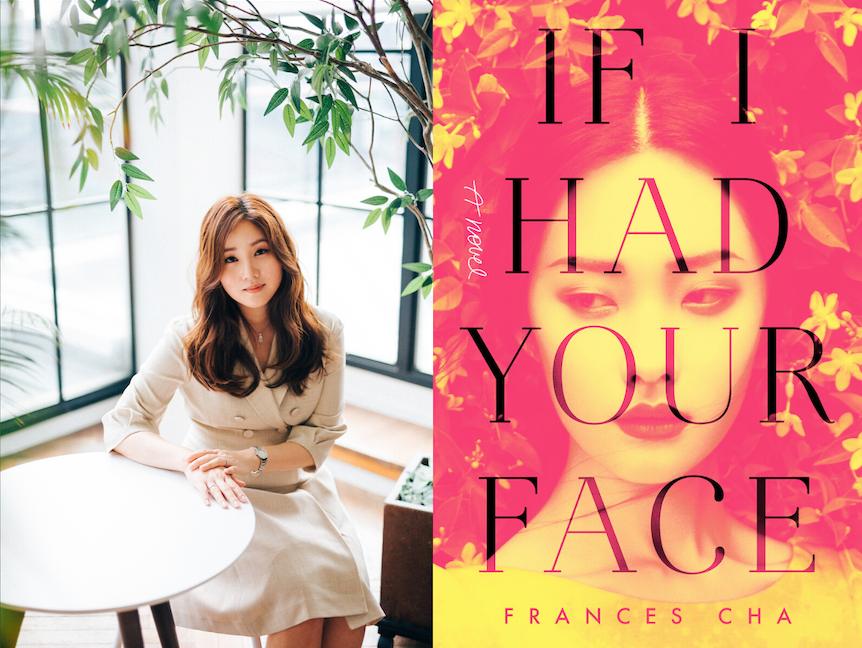

A defender of traditional Korean arts refuses to give up.

August 22, 2012

I have never seen my parents dance. I am not sure if they ever danced in South Korea, before they immigrated to the United States in the 1970s. But decades later, on sweltering summer nights in Seoul, Ho Chi Minh City, Manila, through doors cracked open for a breeze, I have glimpsed other couples spinning in unison, learning to tango and foxtrot.

I understand these people, sweating it out with strangers, scrutinizing their footwork in floor-to-ceiling mirrors. The rewards of dance seem immediate. It looks like romance embodied. Sometimes, I wish dance had been a part of my upbringing, as essential to family and community life as epic supermarket sprees or buffet restaurants. I pencil in dance classes on my calendar, but hardly go. Dance wants a commitment, like anything else.

So when my friend Jeeyeon told me recently about her traditional Korean dance training, I felt a door opening. We were having pho in Flushing, talking about her family and life in general, but when she mentioned her dance teacher and the classes she was taking three times a week, she became passionate. Here was something in her life that was precious, but endangered.

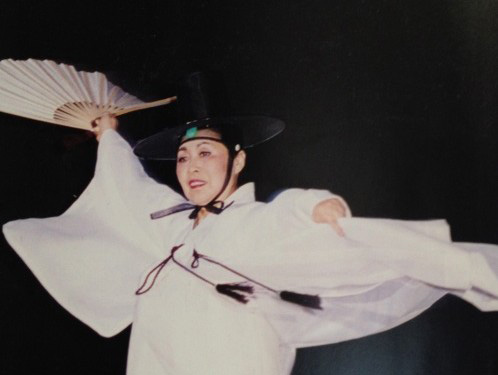

I first met Jeeyeon years ago as a Korean poongmul drummer. Over the years, at pickets and marches, she, along with the rest of her troupe, brought thunderous musical accompaniment and a solemnity to these occasions. Dance was always an element of this art form, as drummers would interlace around each other, jumping and bobbing with the syncopated beat. But learning traditional Korean dance, or muyong, was altogether different, she assured me. She didn’t elaborate.

I went to meet her teacher at her dance studio in Flushing. It was nestled within a compound of other hagwons, or Korean academies dedicated to tutoring or skill-related instruction. Amid the signs advertising hip hop dance, music, art, and martial arts training, there was one that said, “Samulnori. Traditional Korean dance. Korean art school,” from which drumming sounds emanated. When I stepped in, the young students didn’t stop, as their instructor commanded, “Again! Watch your head!” The students dutifully continued bobbing, long white ribbons twirling from their heads.

I saw Mrs. Myoungsoon Choi in the far corner, and she smiled and beckoned me to come to her.

Some people take time to warm up before they can begin sharing their thoughts during an interview. But not Mrs. Choi. She immediately launched into her thoughts. My list of questions sat folded up in my lap, and mostly I listened, much in the same way I thought her students did.

“Honestly, it’s quite sad. In our immigrant society, we value all the cultures of other countries. Golf, swimming, classical music—everyone is so proud, they are spending so much energy learning these things. Ha! What good are they, if they don’t know their own cultural traditions? We have our priorities wrong. For us, for Koreans, culture is always secondary, it’s never first. I do get support from some institutions and foundations, but it’s not enough. Some support is better than no support, of course. But many countries dedicate more resources to culture. Not us.

“Of course, in the end, although all artists are poor, it is particularly hard making a living in the Korean traditional arts here in the United States.

“I understand—economically it’s hard. Mothers should stand up for making sure their children learn these traditions, but they can’t. I have so many students who learn up until college. But then, they end up not mastering the tradition, only learning a part of it. I have to start all over again with the young children.

“Sometimes, it’s so hard I want to quit. The rent, the costumes, the instruments that have to be imported from Korea—all of it costs quite a bit. But when I see the children learning, like this,” and here she gestured at the room full of children, “I get re-inspired. I will do this as long as my health permits.

“I have been doing this for 32 years, and 12 years at this particular location. I don’t outreach through the newspaper or anything. I get my students by teaching all around Flushing, and through word of mouth. There isn’t a school in Flushing I haven’t taught at.”

As she paused, I asked her, “For someone who is a second-generation Korean American like me,”—(at which point she interjected, “Oh, your Korean is so good!”)—“what would you tell them about learning the traditional arts? Why should they learn it?”

“We are Korean. We should learn our roots. We keep only valuing the cultures of others. Historically, things like dance and music were associated with the kisaeng [court entertainers who were trained to entertain kings and the aristocracy, sometimes as prostitutes]. To be accomplished in the arts was not necessarily good, and people with this kind of thinking fear the reputation that comes with learning these arts. My parents, up until they died, never saw me perform.”

As we talked, the children’s class ended. The students took off their hats and bindings, and were slowly picked up by their parents and relatives. The next class filtered in, her basic traditional dance class. Four young women, one of them Jeeyeon, came in and began to wrap brightly colored skirts over their leggings and pants. One young man, the teacher who had been instructing the young children, also began to prepare for the class.

As music began playing from the stereo behind us, Mrs. Choi focused intensely on the movements of her students. Once, she paused them all mid-air, teetering on one foot, and fixed their positions. The music was stirring—a mournful voice rising above and below strings and percussion. The students swayed their arms in front and then behind them, while their feet moved smoothly across the floor, invisible under the long skirts. They stretched, flung, caught, and draped white scarves in the air and along the floor. Every movement seemed subtle, sweeping, focused mostly on the arms and hands, and gave me the impression of leaves floating on a current of water or in the wind.

Could I learn this dance? In fact, was I supposed to learn this dance, or at least understand it, as Mrs. Choi insisted? For Mrs. Choi and others like her, laboring to pass traditional art forms to younger generations, I could understand their sense of loss. I knew why Mrs. Choi felt like such a warrior to me—in order to justify her existence, she had to be.

And yet her sentiments reminded me of Frantz Fanon, who wrote about postcolonial nationalist movements in his book Wretched of the Earth. I recall his statement that any nation or movement that defines culture as a set of fixed traditions results in a culture that is no longer alive. Culture, rather than being pre-defined for people, needs to be generated by them as they live their lives. His assertion has haunted me ever since I read it.

I get hopeful when I think of friends who have organized Korean drumming contingents year after year to bring together queer Asian Americans for Manhattan’s Pride Parade and Lunar New Year parade. By teaching queer and straight Asian Americans across many ethnicities the rhythms of Korean drumming, they have transformed this Korean tradition into a routine that unifies people in a loud and visible way. I wonder what it would be like if traditional Korean dance and the other art traditions of immigrants could be re-inscribed in everyday life, no longer embattled artifacts but necessary and vital instruments. Korean dance to tell the stories of new immigrants! Korean dance to reinvigorate unused public spaces! Korean dance to fight the boredom of a long immigration visa line! You get my drift.

In the meantime, I plan on taking a few lessons. For anyone else interested in learning from Mrs. Choi’s many years of dance experience, she can be contacted at (718) 539-1203. Her dance studio is located at 42-29 162nd Street, off the Q12 bus line.