‘I was pushing myself to write from places that terrified me.’

January 29, 2020

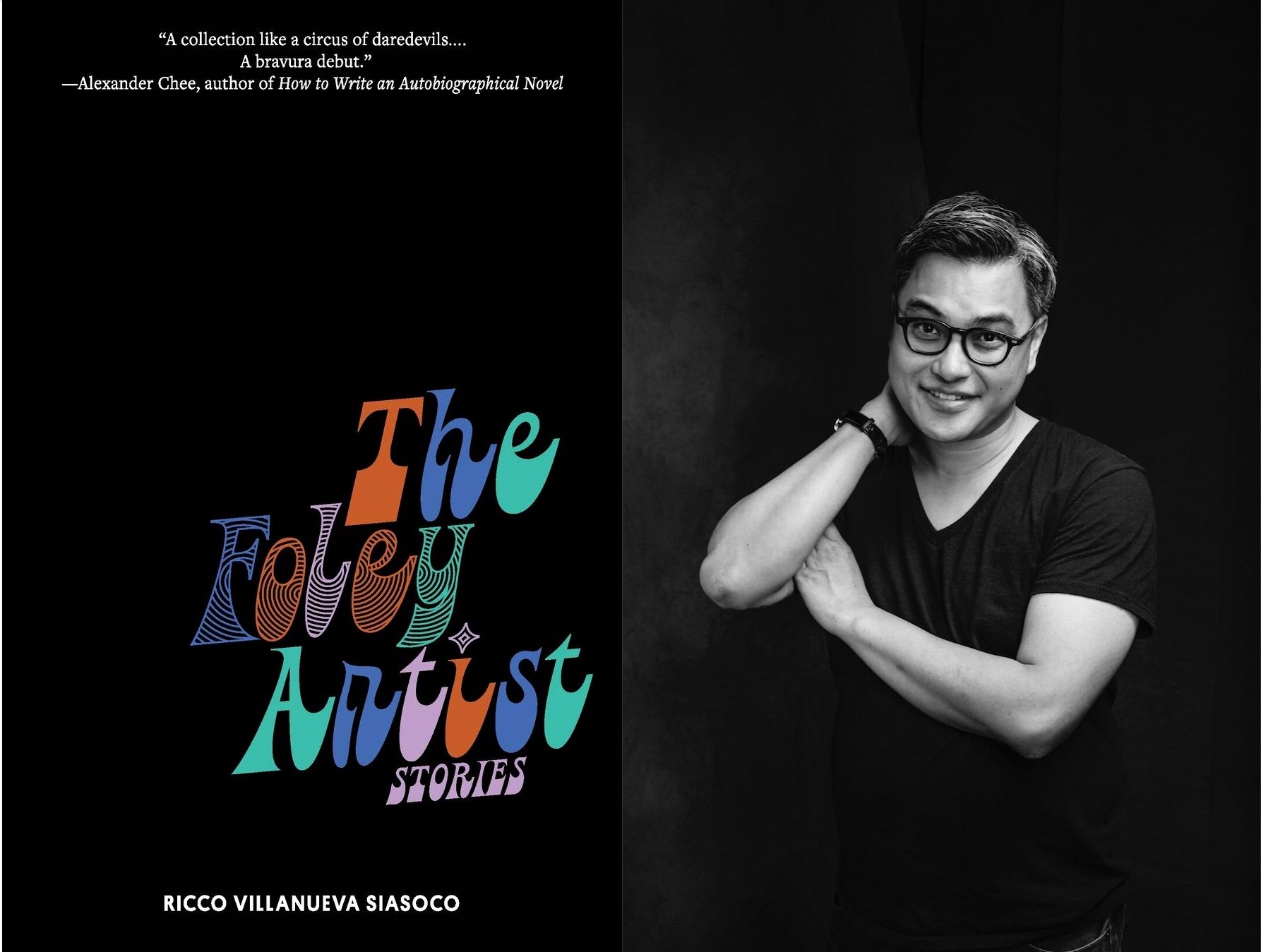

Ricco Villanueva Siasoco’s debut The Foley Artist is a collection of nine interconnected stories that is hard to sum up with a single neat phrase. As Alexander Chee puts it, the book is “like a circus of daredevils.” What is apparent in each story is Siasoco’s playful daringness to take risks in his writing, even as he tackles serious issues with care. At the core of The Foley Artist is a Filipino American family: a single mother and the two children she raises. Their lives are rendered with deep emotional depth as the book follows them across time and space. There is much to admire in how Siasoco makes deft use of the interconnected structure of his stories to showcase character growth, as well as the intertwined yet ever-shifting nature of our relationships with others.

When I talked to Siasoco, I found that he always had a laugh ready, but he also took his time to ponder questions before answering them thoughtfully. In this way, speaking with him reminded me of reading his stories.

— YZ Chin

YZ Chin

I’m a little biased, but I’m a huge fan of interconnected short stories. Did you start out intending to write an interconnected collection?

Ricco Villanueva Siasoco

I do love interconnected stories as well. One collection that I thought of immediately when I started working on one or two stories was Dale Peck’s Martin and John, which has always affected me. What was interesting to me about that collection is that each story had characters named Martin and John, but they were not the same people [across the stories]. It was a little abstract in some sense, but also concrete, which I loved.

And of course I love Alice Munro, Jessica Hagedorn—all these great fiction writers had interconnected stories. For me, when I was writing this story collection I thought: How do I tie these stories together into a literary conceit.

YZC

Can you talk a little more about that?

RVS

Sure. I think about how you can use form to show the relationships within Filipino families. The characters are close, or they speak the same language, or they eat the same food, and I’m thinking about how choices you make as an author—for instance, interconnected stories—show the importance of these stories. Or think about how my friend Gina Apostol uses postmodern work to make commentaries on Asian American and Filipino-ness.

YZC

In your collection there’s a central character who struggles to accept his sexual orientation, and across different stories he appears in different ages. There’s one where he’s in the locker room, one where he’s in the car with his brother-in-law, and then his coming out, later, to his family. It’s the same character, and yet different because we’re seeing him across different spots in time. I thought that was wonderful. Did you write the stories in the order they appear?

RVS

I didn’t write them in the order as they appear in the collection. The character we’re talking about, Noel, is very different in different stories. I think about how I myself was very different in my twenties, then in my teenage years, then in my late-forties now.

I really wanted to think about how Noel matured in his thinking about his sexuality. In “Deaf Mute” he’s got a lot of internalized homophobia. Later on, as he’s exploring his sexuality and being more open to himself about who he’s attracted to in “Wrestlers,” it’s clumsy and wrong. As a writer I was pushing myself to write from places that terrified me and that were super uncomfortable.

YZC

I think that really comes across. I read it as a generosity of imagination.

You have such diverse characters and diverse stories. Is there a common thing that connects them all, or would you say the diversity is the point, like you’re showcasing your range?

RVS

I think the latter. I’m really interested in diversity of range and voice, and adjacent to that, the diversity of the characters. As a writer I’m very down on myself. So often times I set myself assignments. For example, I have a story called “Nicolette and Maribel” about two women. For that I asked: How can I understand women better and deal with some of my own biases? And how can I be generous towards them?

I love that you were talking about generosity; I always struggle to be generous toward my characters. Also, when I’m writing, I want to set myself the challenge of not just presenting a theme or a character; I also want to complicate it by saying, let’s talk about transnationalism in this story. So a lot of my stories have three or four layers. I like not just having one challenge, even though “beginning, middle, and end” or having a full character is already a big enough challenge.

I also wanted, in “Nicolette and Maribel,” to talk about how, cross-culturally, the characters were on completely different pages, tied only by the color of their skin, their ethnicity. But they’re so different. That was my challenge with that story.

YZC

There was a minor book Twitter “controversy” about how some people read stories in a collection out of order. What’s your take?

RVS

Personally, I love it. As a reader, I don’t feel an obligation to start at story one and end with the last story. I do think that in my collection the stories are very different; some are very dark and some are more hopeful. When I think about how I crafted my collection in a certain order to have an emotional arc—you’re not going to hit that emotional arc [if you read out of order], but I’m also fine with that.

One of my favorite story collections is [Denis Johnson’s] Jesus’ Son. If you’re a writer [that book] is just a touchstone. I think any of those stories can be read out of order. But also there is an arc that Johnson put into that book, and it’s a very traditional arc.

YZC

I’m hearing it come up a lot, how you set challenges for yourself when you write, or you try to push yourself, make yourself uncomfortable, set yourself tasks. Is that how you generally approach writing?

RVS

I think if I’m happy writing, there’s something wrong. We’re just masochists, right? Spending hours by ourselves. I feel like if I’m going to write well, I have to get away from tying things up with a neat bow. In contemporary American fiction there’s a lot of open-ended endings, and that’s how we get these traditional workshop stories that are so-called real-to-life. And for me, okay, you can have an open-ended ending, but more interestingly: let’s play around with the whole structure and the characters. Let’s do something taboo. And that’s super interesting to me as a writer. Especially since in real life I’m so boring, it’s great to go into these deep areas.

YZC

It’s interesting to me that the first story in your collection is set in a restaurant. In what ways are you playing with Asian American representations of food?

RVS

The restaurant setting is very much one that has sentimental meaning for me. My father loved this restaurant called The Rice Bowl in Des Moines. It’s a fictionalized version in my story, but there’s a real place. That to me intersected with a wild idea I had when I went to an East Village restaurant with Asian drag queens in New York, maybe Lucky Cheng’s. I love that place. I thought: Well, could there be Asian drag queens in a restaurant in Iowa? Then you laugh to yourself and you think: That is ridiculous, and impossible. And then—you just try it. So whenever I was working on that story, I’d show it to a friend or a teacher, and they’d say: You have too much stuff in here. This is really a novel. Again, it’s that challenge I set for myself, where I’m just going to throw everything in. See how I can handle it. If there’s too much I can always take out some.

A story that centralizes Asian Americans has to [strike a] balance with how important food is in a genuine sense. For me, [that’s] by naming it. When there’s food in a story, it is calamansi. It is lumpia. But I’m not describing the fragrant smells from the dishes.

YZC

When you said earlier that your father’s favorite restaurant is The Rice Bowl. Has he ever read the story? I’m curious how other Asian or Asian American writers navigate their parents’ reception to their work.

RVS

I don’t know. Both my parents passed away in the past few years. I felt an internal pressure to write all these memories of them in the world before they passed away. Unfortunately I had one or two stories published when my father died. My mother died two years ago. It’s really funny to have a story collection about Filipino families and parents when my parents can’t read it.

As educated elites in the Philippines, I think my immigrant parents were really open to the stories that I had published. Your question gets to something deeper, which is that Asian American need for acceptance from our parents for these completely non-sensible careers. Many of our Asian American parents came over after 1965 as a professional class (doctors, lawyers, engineers) and then their second-generation children are like: Let me pick a totally impossible career.

YZC

Can you recommend other Filipino American writers we should read?

RVS

Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers is top of my list right now. Full disclosure, she’s been my friend for 20 years. I think we share a similar curiosity about Filipino American culture, a willingness to question and interrogate. She tackles subjects like family abuse, body image, disease. I would also say Mia Alvar’s In the Country. And Randy Ribay, whose Patron Saints of Nothing just got nominated for the National Book Award. And of course another friend, R. Zamora Linmark, is pushing into YA literature very intentionally with The Importance of Being Wilde at Heart.

YZC

I thought it was interesting that you titled the collection after a character who maybe at first glance doesn’t seem the most central. The Foley Artist is a lonely old man who wants to watch videos.

RVS

I chose “The Foley Artist” as the title of the collection because that story has a lot of meaning for me. In one sense it’s [about] respect for elders. [And in another] sense to know our history. So the character is a manong; he came over in the 1940s because of the U.S. need for foreign labor to build up our economy. That’s why this whole generation of manongs came over. But also I love the idea that foley artists reproduce sounds of life [for film] and make them more beautiful. For me it’s very evocative of life, of other characters and stories. I thought about some of the other story titles that have to do with queerness, but “The Foley Artist” allows a reader to impress upon it anything they want.

YZC

What’s a question you wish people would ask you when talking about your book?

RVS

I wish folks would talk more about intersectionality instead of siloes. I think readers want to focus on one aspect of identity—on race, or sexuality, or country of origin, or gender. Those of us who identify as queer and Asian and first-generation American, we don’t separate those categories when we wake up in the morning and go to work, or when we love or argue—it’s all there.

YZC

What does it feel like to work with an indie press that focuses on highlighting Asian and Asian American writers?

RVS

That’s a great question. Gaudy Boy is so amazing and I never would have imagined myself publishing with an indie press that has an explicit mission to further Asian and Asian American voices. One important thing I’ve learned from the publisher, Jee Leong Koh, is thinking about transnational publishing. I’m Asian American, I have a very strong American individualist identity. And to think about how the book could appear in Singapore or Malaysia, how Asian readers would interpret it, has been fascinating. So that was a whole dimension of feeling, as Gaudy Boy would put it, that I’d never thought of.