It is a wonder that anything was left of the road.

March 30, 2023

This piece is part of the Climate notebook, which features art by Katrina Bello.

“Startled American citizens, even those who prided themselves on a fair degree of education, pulled down their atlases to learn where and what were these Philippine islands about which they had known practically nothing but the name.”

—William Cameron Forbes

1. Told of a “paradise” somewhere in the hills1

To their delight, they found

the beautiful

rolling hills of Baguio and the little plain of La Trinidad

covered with

thick, rough grasses and great pines

valleys water-courses tree-ferns

a reddish clay

breezes even in the heat of day

clear hours to make out-

door life delightful at night

a wood fire of pine logs

To seek a shorter route

into the cañon of the Bued

River

here the second appropriation was

exhausted

this time Colonel

Kennon had

four thousand men at work

blasting his way through friable

rocks

it was

often necessary to walk, leading the horses

into the future city It was by this

route the great landscape architect

Burnham made

a comprehensive plan

The river was

crossed by rudely constructed span bridges

wood swung on steel cables

rainfall sometimes

reaches two hundred and fifty inches a year

the proportions of a cloudburst

it is a wonder that anything was left of the road.

It was

within the bounds of reasonable possibility the ulti-

mate city

Having dreamed of the city

American adminis-

trators and engineers set about to build

the form of the vision A committee

selecting names

words of good

American use with Igorot words

North, South Outlook

Bua, Kisad, Pakdal

A country club

at first little more than a shack

A hospital residences for officers

barracks for men

a detail of fifty

prisoners arranged

ornamentation of the twenty-five

acres set aside for the Governor-General’s estate.

The forest in question²

common property of a certain

community opportunity

structure rule of exclusion challenged by groups who

invoke national law

the uncertainty of current land tenure

increasing degradation loss of biodiversity

common

property into capital Mt.

Pulag Mt. Polis probably the last mossy forests in the central

Cordillera

Names are Maps to Absences Hiding Behind Other Names3

1. from William Cameron Forbes, “Baguio,” Chapter XIII, Vol. 1; The Philippine Islands in Two Volumes, Houghton Mifflin, 1928.

2. from June Prill-Brett, “Changes in Indigenous Common Property Regimes and Development Policies in the Northern Philippines,” 2003 RCSD International Conference.

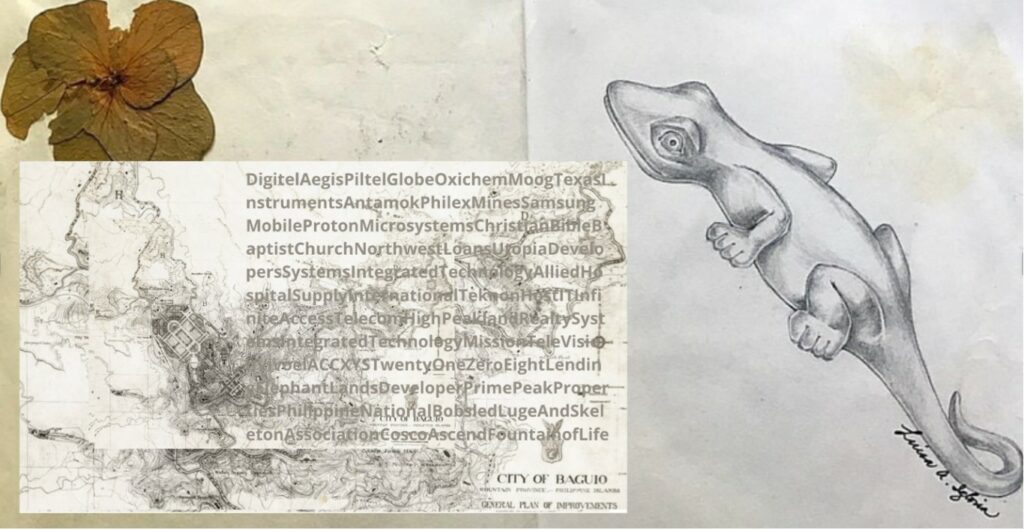

3. collage of Daniel H. Burnham’s city plan of Baguio, 1905, on which I have superimposed some names of companies with operations in the present day; the background to these is a simple mixed media spread composed of my pencil drawing of a lizard—a motif appearing in Cordillera folklore—and a dried, pressed milflores (hydrangea) bloom.

Author’s Note

“Told of a ‘paradise’ somewhere in the hills” and “The forest in question“ are erasures from a longer work-in-progress in which I think about subjects important to my work: language, history, culture, postcolonial and transnational identities, exile, geography, place. It is also necessary to consider the impacts of the pandemic, ongoing global climate change, and environmental degradation especially as these are borne by people and communities of color. The blueprints for what we experience in these current crises were laid out during the age of exploration, when Western nations set out to colonize other territories in their bid for empire.

A specific example is Baguio City (where I grew up). Early in the period of American colonial occupation of the Philippines, American architect Daniel H. Burnham was commissioned to draw up the plans for Baguio as a colonial hill station. The displacements of indigenous people, land, and material culture from that period are directly connected to the current issues of social and environmental degradation in the city: urban blight, air and water pollution, and watershed and biodiversity loss even as development continues to privilege corporate interests and the tourism industry.

The first source text is William Cameron Forbes’s The Philippine Islands in Two Volumes, specifically the chapter in Volume I on “Baguio.” Forbes was appointed Commissioner to the Philippines in 1904 and charged with the physical development of the American colony. Secretary of War William Howard Taft had instructed Forbes to hire an architect; eventually, Forbes wrote to his friend Daniel H. Burnham: “It is one of the projects of the Philippine government to build a new city five thousand feet above the sea, which will be to the Philippines much what Simla is to India. It is part of the plan for me to get some landscape architect to go out and try to lay out a new city, and in addition to draw up plans for the development of Manila.” The chapter on Baguio details the American fascination with rumors of an upland “paradise” in the northern part of the country. Because it was temperate year-round, they lost no time converting the area that was home to indigenous Ibaloi and Kankanaey into a hill station and the summer capital of the archipelago.

The second source text is a paper by scholar and anthropologist Dr. June Prill-Brett, which she delivered at a 2003 RCSD (Regional Center for Social Science and Sustainable Development) International Conference. Dr. Prill-Brett, who is of indigenous Bontok ancestry, is one of the first native Philippine anthropologists and the first Igorot anthropologist to earn a doctorate in anthropology from the University of the Philippines (1987). Her paper gives an overview of postcolonial development policies and their impact on Indigenous Peoples (IPs) in the Philippines, particularly in the northern Cordillera region. After the increased implementation of state-managed processes for reckoning property during the American period, ancestral land and land use rights formerly held by indigenous communities became more susceptible to opportunistic claiming by commercial ventures.