Where the “Yellow Peril incarnate” meets one novelist’s depictions of China and its diaspora in the early 20th century

February 4, 2014

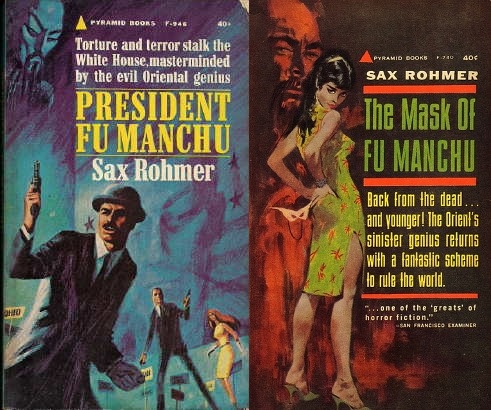

I never expected to write an essay whose title paired an extraordinary, fictional supervillain with a Chinese writer best known for his tales of ordinary Beijing life. And I doubt I ever would have, if I hadn’t gotten a pair of emails discussing decisions made by publishers to reissue novels from the early 20th century. The first email arrived in February 2012 from a Wall Street Journal editor who wondered if I would be game to write about the decision Titan Books had made to republish Sax Rohmer’s sensationalistic series of Fu Manchu novels. I took the bait, which led me to delve deeply into the strange and lurid world of Rohmer’s potboilers. Until then I had known about the British writer’s most famous and infamous creation by reputation alone—Rohmer describes him as “the Yellow Peril incarnate”—but had never actually read a novel featuring the fiendish Dr. Fu Manchu.

The second email, which came in mid-2013, was from a publicist at Penguin China who told me that her publishing house was bringing out new editions of two novels by the Chinese writer Lao She, Mr. Ma and Son and Cat Country. Unlike Lao She’s best known work Rickshaw Boy, whose plot unfolds in the writer’s hometown of Beijing, these two novels are set outside of China—one in London, where Lao She taught in his youth, and the other on Mars (that got my attention!). The announcement led me to expand my literary horizons in a different direction; I learned that Lao She could not only write about more locales than I had imagined, but also could stylistically be much more fanciful and cynical (Cat Country) and more playfully satiric (Mr. Ma and Son).

While I was reading the Fu Manchu novels and as I wrote about them for the Journal (“From China with Love,” October 5, 2012), Lao She never crossed my mind. It wasn’t until I had finished the Penguin reissues that I was struck by how many curious connections could be traced between Rohmer’s devilish doctor and the Chinese author who had just taken me to London and Mars.

Before describing those curious connections, a bit of background on Fu Manchu and Lao She is in order. Let’s begin with some facts about the fictional member of the pair, starting with his name. It is telling that Rohmer continually calls him Dr. Fu Manchu. The honorific flags the mad scientist side of his character, for his power allegedly lies in drawing on both the “mysterious” knowledge of the East and “scientific” methods of the West. This combination was designed to alarm audiences in the West, due in part to the timing of Fu Manchu’s first appearances in print in the early 1910s and soon after that in British and Hollywood horror films. At the time many in the West were still reeling from the fact that Japan, an Asian country, had recently defeated Russia, a European one, on the battlefield. The defeat, due largely to the extent to which the Japanese had embraced and mastered the use of Western technologies, would previously have been considered unimaginable given how racial hierarchies of the time were expected to play out.

The novels featuring the villain may have popularized his name, but it was movies such as 1929’s The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu that took his fame, or rather infamy, to a truly global level. Fu Manchu became a fiend as well known as any other in the annals of world literature—right up (or perhaps down) there with Moriarty and Macbeth. His trademarks included an unquenchable desire to wreak vengeance on the West; great intelligence combined with a sadistic streak; and invincibility, for no matter how many brave British heroes thought they had vanquished him, Fu Manchu always rose again.

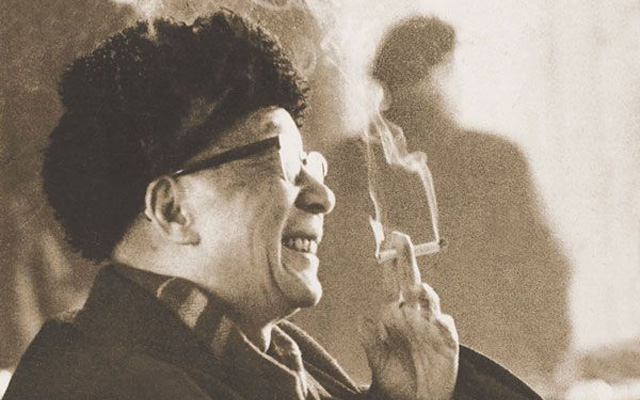

Lao She also made his mark in the early 20th century, with his short stories and novels—albeit ones he wrote rather than in which he wreaked havoc. Born in 1899, the child of an ethnic Manchu, he often went by the Chinese name Shu Qingchun in private (the Shu standing in for the Manchu surname Sumurua), using Lao She as his nom de plume. His best-known novel, published in the West as Rickshaw Boy, told the tale of a rickshaw puller in Beijing in the 1920s. The novel was praised for its realistic portrayal of everyday life and the film based on it won a major cinematic award. The same can’t be said about Rohmer’s novels or the movies they inspired.

One final contrast between Fu Manchu and Lao She is a tragic one, but worth noting. The writer had no magical ability to defy death—he passed away before his time in 1966, due to a series of events that Ian Johnson describes in a masterful essay that introduces the new Penguin edition of Cat Country. Lao She, then 67, became an early victim of the Cultural Revolution. Like many intellectuals of the time, he had been a target of Red Guard fury, deemed suspect in part because he had lived in England in the 1920s and then later in America. That he had returned from the US when Mao took power in 1949, living in the newly founded People’s Republic of China, and had gone on to write plays that were seen, for a time, as suitably in step with the new order did not spare him. One morning during the summer of 1966, late in what has become known as “Red August”—a month during which more than 1,500 people in Beijing viewed as politically suspect were killed or took their own lives—the writer’s lifeless body was found floating in a pool of water in the capital.

Why, given all these differences, did reading Cat Country and Mr. Ma and Son leave me with a sense of Lao She and Fu Manchu as connected? Reading about the feline-like humanoids in Cat Country, the author’s sole foray into science fiction, triggered the first parallel. Published in 1932, at a time when the country was politically fragmented and misgoverned at home, and threatened by Japanese invaders moving across its borders, the novel served as a lightly veiled satirical critique of 1930s China. Aside from the human narrator,  who arrives on Mars on a space ship, the characters in Cat Country are all, not surprisingly, beings who physically resemble large cats. Although the narrator identifies as Chinese and speaks of his desire to return to his beloved China, Lao She clearly intended his fellow countrymen to recognize the Cat People of the Red Planet, who remain apathetic and self-involved in the face of a dire foreign threat, as versions of themselves.

who arrives on Mars on a space ship, the characters in Cat Country are all, not surprisingly, beings who physically resemble large cats. Although the narrator identifies as Chinese and speaks of his desire to return to his beloved China, Lao She clearly intended his fellow countrymen to recognize the Cat People of the Red Planet, who remain apathetic and self-involved in the face of a dire foreign threat, as versions of themselves.

In the case of Fu Manchu, when we first meet our villain Rohmer describes him as having a “feline” look. It is just one of many descriptive devices that make the villain seem more monstrous than human, a character who is presumed to be of this world, but should be treated by contemporary readers as something out of science fiction rather than a more realistic variety of literature.

In both Rohmer’s novels and Cat Country, then, we find sensationalistic plots and cat-like characters that readers are meant to view critically. Yet while Rohmer’s feline-featured villain is ferociously strong and capable of hatching complex conspiracies, the Cat People in Lao She’s novel are lampooned for their weakness and inability to organize and think strategically. Most importantly of all, Rohmer only imbues members of groups other than the one he belongs to with traits that dehumanize them (Fu Manchu’s minions of various nationalities are routinely presented as subhuman in one way or another), while Lao She uses the technique to try to make his countrymen wake up to what he sees as their shared failings.

The Fu Manchu link to Lao She’s Mr. Ma and Son is more straightforward and easier to track. That novel combines elements from several genres and shifts between tones, mixing melodramatic depictions of romances (that end badly) between star-crossed lovers of different nationalities, with farcical passages describing amusing misunderstandings and cultural clashes between a middle aged British landlord and her daughter, and between the two of them and the Chinese father and son who rent a room in their house. One key element throughout the book, though, is a sustained effort to satirize and debunk the stereotypical views of Chinese people that many Britons held early in the 1900s. Lao She knew these well, having encountered many kinds of bias during the period he spent living and teaching in England while in his 20s (a sojourn insightfully detailed in Anne Witchard’s Lao She in London). While not focusing on or even mentioning Fu Manchu, it is clear from the context in Lao She’s works—including allusions to the role that films featuring Chinese villains played in shaping popular images of China and its people—that he is taking aim at the way that Rohmer (along with related figures) presented his country as one made up of depraved and savage people.

One fascinating thing about Mr. Ma and Son, as Julia Lovell makes clear in her brief, astute “Introduction” to the Penguin edition, is this concern with undermining and correcting misconceptions about China and the Chinese that proliferated in early 20th century British—and more broadly, Western—popular culture. Often, Lao She uses humor to make his points, like when the British landlady in the novel is about to meet potential Chinese renters and puts a copy of a book about opium on the table so that her visitors will see that she knows about their part of the world. That said, the book also has its share of passages that describe, via polemical statements rather than comic twists, how angered Lao She was by the Yellow Peril prejudices of the time (he writes at one point that London’s residents attribute “every crime under the sun” to “the community of hard-working Chinese” living in their midst, “who are simply seeking their living in a strange and foreign land”).

One final Lao She connection to Fu Manchu must be mentioned: an incident that plays out in at least one of the Fu Manchu films to explain his hatred of the West parallels an episode in Lao She’s life. The events in both cases took place in the aftermath of the famous 1900 siege of Beijing’s foreign legations carried out by the Boxers, anti-Christian insurgents whose violent acts took Yellow Peril fears to unparalleled heights. A consortium of foreign troops marching under eight different flags stormed into North China and lifted the siege. The invaders then launched a series of brutal campaigns of retribution, during which European, Russian, American, Indian, and Japanese soldiers killed many Chinese who had never been Boxers at all, or even supporters of the insurrection. The victims included a significant number of ethnic Manchus. This group was seen as complicit because of a fateful decision made by leaders of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), a Manchu ruling family: to support the siege. Just as memories of Boxer violence have cast a long and disturbing shadow over Western views of China, stories about what Eight Allied Armies did in Asia have cast a long and disturbing shadow over Chinese views of the West and Japan.

When Lao She was an infant, his father was among the local Manchus killed by the invaders, and in the 1929 film The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu, the action begins with an eerily similar incident. In the fictional case, though, it is not Fu Manchu’s father who is killed but his wife and child. The violent act instantly transforms the doctor (who despite having a name including the term “Manchu” was not, as far as I know, ever described as belonging to that ethnicity). From someone positively disposed to Westerners, he turns into someone who sees nothing to admire about the West and is determined to wreak vengeance against the entire white race.

This brings us to a final contrast between the man of fiction and the man of flesh: Lao She was an eloquent critic of anti-Chinese prejudice, but he was no xenophobe. His feelings about the West were complex and ambiguous. While aggravated by the extent of anti-Chinese sentiment in England, he developed strong friendships with individual Britons he met in London, and despite being infuriated by the racism he encountered, he looked back fondly on his time abroad. Lao She once claimed that he “didn’t need to hear stories about evil ogres eating children and so forth; the foreign devils my mother told me about were more barbaric and cruel than any fairy tale ogre”—and the tales she told, he noted, were “100 per cent factual, and they directly affected our whole family.” And yet, just months before he was hounded into committing suicide, as Lovell notes in her introduction to Mr. Ma and Son, he was waxing nostalgically to a visiting British couple about the “great kindness” he encountered in England and the beauty of London in springtime.