We heard a glass break, then saw our mother, saw what looked like tears.

February 25, 2022

It was just a ghost story. But one we knew well, one that was like family. Haraboji would only tell it in the evenings in his native tongue—the one we couldn’t speak well but could understand.

“You speak like a foreigner,” he would say now and then when he heard us speak mere fragments to our mother. (And we’d apologize.) But he’d wave his hand at us, as if swiping a fly away.

“It’s not your fault,” he’d say. “This is what happens when you leave, when you try to start over.” And our overworked mother, cigarette in mouth, would snort in the other room.

“The land doesn’t know you; it’s still too fresh. Still…”

We had grown up enough in the language to be able to listen, to memorize, and this always seemed to please him. When he had finally left the past and resettled with us in America, we became his perpetual audience—one who didn’t interrupt, who clung to each word and each action, to each regret. (And there were many.) We let him rant, too, so long as he got back to the story.

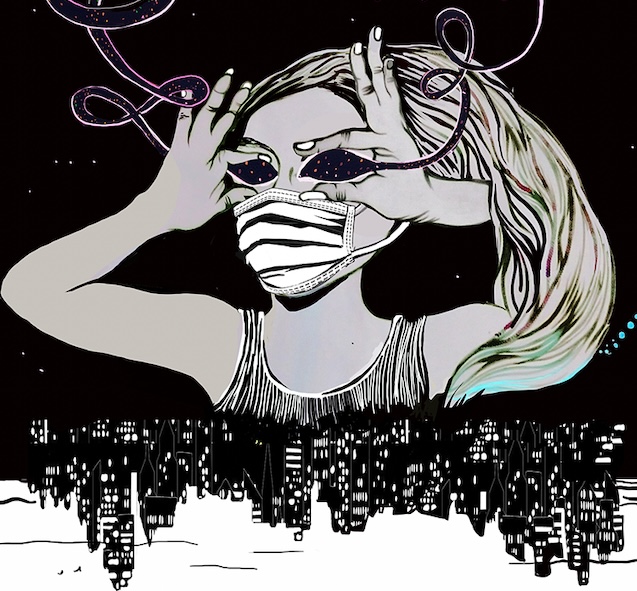

“Honbul,” he’d say, and light a cigarette, slowly exhale. Always, as if to add to the effect, he’d make sure to tell us the story at dusk when you had to refocus your eyes and make sure they weren’t playing tricks on you.

“Honbul,” he’d repeat, and flick the lighter on and off, on and off.

“Ghost flames,” we’d say, the words translated between us, then focus on the little flame in his hand, imagine it roaming the scorched earth on the horizon, searching. Always searching.

He’d nod, begin. “Once upon a time, there was a mother and a child.” (Always once upon a time and always a mother and a child.) “They were fleeing the small village where ten generations had lived.” (Always, they were fleeing.)

“Ten generations,” we’d repeat. “Ten.”

“July, 1950.”

“July, 1950,” we’d repeat.

“The American GIs.”

“Americans,” we’d say. (Like us, we’d think.)

“Somehow that child survived. Near the two tunnels. Somehow that child,” he’d say, then look out into the distance. “Somehow he made his way out from beneath the bodies at No Gun Ri.”

“Somehow,” we’d said, prematurely.

“Yes,” he’d say, before closing his eyes and continuing. “Somehow.”

“The ghost mother looks for her child,” we’d say.

“Always,” he’d say. (Because a mother always looks for her child.)

“Always,” we’d repeat. (Because fathers aren’t always present.)

And we closed our eyes for a moment, tried to recall our father, but he only existed in a paternal outline.

“But,” Haraboji said.

“But,” we repeated and looked at one another, waiting for some contrast, an amendment to the story.

“Uri omma doesn’t know she’s dead.”

“Our mother?” we echoed. “Dead.”

“Appa,” our mother suddenly said.

“My mother doesn’t know the bullets, which she shielded me from, missed. She doesn’t know the bombs will make our country a desert. And she can’t know I will survive.”

“Appa,” our mother repeated, then spoke words we didn’t yet know, could not yet translate.

“Buried,” he said.

“Buried?” we repeated.

“Beneath those bodies, all that flesh.”

We heard a glass break, then saw our mother, saw what looked like tears.

“So she burns with anger,” he said.

“Burns with anger,” we repeated.

“As she walks the land looking for her son.”