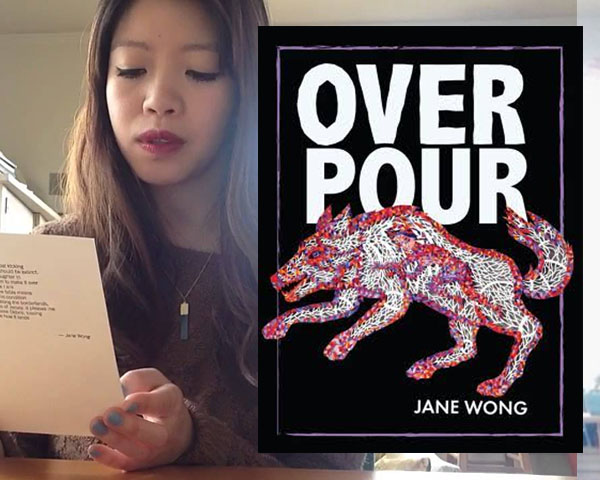

The poet talks about her debut collection, sharing silenced histories in her writing, and being a “wild girl poet.”

June 6, 2017

Jane Wong’s debut collection of poems, Overpour, is a sonic smorgasbord—the poems contained are feral and fierce, their images wild with rapture and tenderness. With their language, Wong’s poems rearrange the remnants of chaos, war, exile, and family. In “The Act of Killing,” Wong writes, “It is early and I have no one to trust./The sun wrestles wildly about me,/throwing light in unbearable places.” Indeed, the poems in Overpour resist easy categorization—they wrestle wildly with the complicated questions they pose. The light contained in Wong’s poems is often beautiful, but their beauty often creates disquiet rather than comfort.

Read Jane Wong’s poem “Pastoral Power” from Overpour below.

Sally Wen Mao

In “No Need for the Moon to Shine On It,” you write “Murder is to mitosis is to mercy,” a stunning example of the way the images in your poems metamorphose in surprising ways. They’re always shapeshifting, delighting and disrupting the senses. How do you begin a poem? How do you approach image? Can you tell me about your poetic process, or if you have multiple processes, which one works the best for you?

Jane Wong

I am so grateful for this question about shapeshifting images! This is what draws me to poetry and writing more broadly—the way I can pull an image in so many directions that it changes into something entirely different. I always begin by writing down images. I feel like I’m a collector of what I see in the world—anything that makes me laugh, makes my heart hurt, makes me wonder: What is that doing there? I have so many notebooks and a giant Word document called “NEW NEW NEW,” sprawling over dozens of pages, with these images I collect. It’s like a gem-filled garbage dump. That’s how I like to think of it. And when I want to write a poem, I’ll take 10 of those images from my notebook or Word document and arrange them on a page. I’ll move them around; I’ll let them grow and shrink. I’ll let whatever emotional force is driving me that day to pour into those images. How we look at the eyelashes of a horse will differ depending on how we’re feeling, depending on what pressure we give the image with surrounding language. In fact, here are some random images I have piled up, just as an example (you might see these later in future poems):

Filling a can of soup with water

The overgrown squash too heavy to carry

My mother washing dishes: “This one is trying to run from me”

How a picnic table feels in the rain, its legs sinking into its own muck

Don’t leave your legs dangling about like chum

My hair all static, tangents in the air

How men feel like they can touch my hair, just like that, like swatting away a fly or touching the edge of a fence

SWM

The forcefield at the center of Overpour is your mother, who exists in the book as a matriarch, a totem, a goddess in many incarnations. How do you approach your mother as subject, and what is your process of embodiment, especially when you write in her voice? Moreover, when you recreate her, do you feel that the voice that results is a conflation between Jane and mother?

JW

Yes, all the above! Forcefield, indeed. My process of embodiment is always trying to see her as something more than just my mother; I want to see her as a daughter in her own right, as a sexual being, as an ex-wife, as an angry horde of bees, as a baby, as an exhausted postal worker who works night shift, as a fighter, as gentle aloe. Thinking about Gloria Anzaldúa’s declaration about being a border woman, I want to honor my mother’s own border-ness—her many dimensions and contradictions. Being raised by a young, single mom, I often took on maternal roles for my brother. In this way, I certainly feel like there is a conflation of identity in terms of necessity and adoration. I knew I wanted to dedicate my book to her. I wrote: “For my mother, Jin Ai, in awe.” I wanted everyone to know her name. Because she is Jin Ai. And she is sublime—powerful, beautiful, and terrifying. Awe-inspiring. When I write in her voice, I feel like I understand her and myself better. Sometimes I literally put on her clothes.

SWM

Your poem “Field Notes Toward War” begins with “The war is not over.” I was moved by your TED Talk, when you told the story of how you learned about Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward campaign and its resulting mass famines, your stunned and emotional reaction to this history. My family also has countless stories of surviving or not surviving this famine and other catastrophes—most remain untold. I feel that these unspoken, unaccounted for periods of history impact our lives in invisible, biological ways. I feel that strongly in your poems. What is the role of history in your work, and how do you want your poems to address history? What war is not over? What are your questions, and how do you grapple with them as a poet?

JW

Sally, thank you for sharing with me! That shared intergenerational impact—albeit different—is precisely why I want to write about history. I want for us all to share our unspoken, forgotten, and silenced histories. It’s a reckoning to uncover how history—particularly that of migration, war, and trauma—has trickled down into our lives. This poem was particularly difficult to write. I wanted to grapple with this large distance between my family’s experience in Maoist-era China with my own upbringing in New Jersey. How can I bridge famine with growing up in a restaurant? Not much time has passed. I write: “Together, my relatives carry the bodies./I carry this bag of leaves into the garage.” In my dissertation, “Going Toward the Ghost: The Poetics of Haunting in Asian American Poetry,” I consider what it means to rewrite history—to move toward recreation and imagination rather than “hard” research. For, what are facts really without narratives? In this way, I’m not interested in “getting it right;” I’m interested in how I feel about that very silence you speak about. Why is my family silent?

SWM

Who are the ghosts that haunt your poems? Are they even identifiable? Do they have identities?

JW

Multiple identities, certainly. My missing family members during the Great Leap Forward. I do not know their names. My grandparents on my father’s side: my Yeh-Yeh and Ng-Ng who raised me and recently passed. My Yeh-Yeh had a long whisker that jutted out from a mole that would dip into a cup of tea. My Ng-Ng had a jade bracelet that turned purple; she grew giant tomatoes in the yard when my mother was pregnant with me. China itself is a kind of ghost.

SWM

“The Poetics of Haunting” is your dissertation and you’ve lovingly built a website devoted to some of the tropes in your academic work, where you interview APIA women poets. How has your academic research into Asian American poetry helped shape your poems, and vice versa, how does your poetic practice shape your critical analysis? Is it a symbiotic relationship?

JW

Yes! You were my very first conversation; we talked about Anna May Wong, literary lineage, and refusal. I finished my Ph.D. in English at the University of Washington last year and am also proud of my scholarly work. The completion of my dissertation coincided with my first book coming out; I think this coincidence reflects their symbiotic relationship. I am first and foremost a reader. I’ve always been a voracious reader; I grew up in the public library (i.e. free babysitter, according to my mother) and worked there for four years as a high schooler. As an Asian American poet, it’s very important for me to support, champion, and close read the work of my peers, my family—across multiple time periods. My scholarly work is deeply invested in public scholarship and personal narratives, including my own. Of course, I couldn’t help but think about my dissertation while writing “When You Died” (a series of poems to my missing family members during the Great Leap Forward). During my dissertation defense, even though it’s a critical program, I began and ended with two poems inspired by my scholarly work. Being interdisciplinary makes total sense to me.

SWM

Once, in a Kundiman gathering in 2013, Marilyn Chin asked us if we were “wild girl poets.” We looked at each other and then said, “Ummm, yes! That’s us!” Tell me, now that four years have passed, in what ways have you become wild? What’s your definition of a “wild girl poet”?

JW

I’ll never forget this moment! I was actually wearing my mother’s fur and feeling wild in embodiment too. Speaking of Chin, I think about her line from “Brown Girl Manifesto (Too)”: “a bouquet of fuck-u-bastard flowers.” I think being a wild girl is not caring about what others think of you, especially when they have low expectations of you. Being a wild girl poet is also having a crew of wild girls fighting with you, when you are tired. It’s about resistance, about taking risks, about matrilineal and literary lineage, about laughter, about not being afraid of being too loud or too quiet. About listening closely to what rustles under the ice. About cultivating your own power and the power of the people you love deeply.

Pastoral Power

You see: we have this idea of hunting each other.

The impact of the sun on your wrist is first degree.

The racket of birds and my knife is second degree.

Each blade of grass presses upon me as I rest too

long, spring and none. The nightly news runs

across my face, reads: the crime rate is tenth degree.

A heat wave sweeps over the Turnpike, sunflowers

fall along the Shrewsbury strip. In the car, my father

turns too fast and my mother slides across the seat,

window-face and all circumference. I am wrapped

in her sweater, a failing sight. Each signal I see

sees me: helicopters trailing through wool light.

Sometimes, I think: can Walden exist in China?

Returning to nature is a luxury we keep, like this

floral soap I can’t bear to clean my filthy face with.

To leave the village, to return to the village in

a better dress. My cousin pissed out of a moving

van and there was sun, suffocating so. Sun

glimmering in the fish I eat down to the bones.

My life full of debt, indebted, in death do us.

My mother said the groundhogs ate all the eggplants.

And so she hit them with a shovel, one by one.

Little murders, little murders, peace unto you.

Fat spider of dread, spun up in half-eaten

crops. A good year, a bad year, another year.

To wash silk, you must wash it by hand or pay

someone to wash it for you. Red washes out

of an apple and the spell is broken. In Jersey,

the neighbor kid shows me a hold. “I’m digging

my way to China,” he says. In winter, rabbits

nestle in the hold and freeze, ears first. I want

everything to spring up from the ground: grace,

forgiveness. I want the sun to stop following me,

to file a restraining order against the spiny beast.

Climb up on these shoulders of miniatures to see

the fallowing wilderness. Replicas of replicas

and the science fair kind. If I say the volcano will erupt

now, you better believe it. You better bail out

the sea, kill those geese in the parking lot and eat

them for dinner, dressed in rosemary and tar.

Five star meal, five stars in the night. Shining,

how I mistook a fountain in Vegas for my mother.

How I mistook Shenzhen for a forest of sneakers,

this economy in growth. I smiled from ear to ear,

glued in moss, the cheapest form of saccharine.

To those who owe and those who own us.

I might die paying off my loans if they don’t

begin accepting dandelions. Defeat: pumice

trying to sink, 130 million migrants going

home for the new year. February, brace

your face for insults. My brother kicked

a raccoon out of the garage and cried for

days. Was it ever a question of sympathy?

In July, clusters of sun gather in secret

societies. The bangs began charging for sleep.

A tourist spits into a hot spring on a breezy day.

A crane lifts a child out of a well and there is

no television crew. Clearly, discomfort makes

trees grow taller. With fertilizer, we can all shake

from the stems. My legs, dangling over the overpass.

Today, route 18 is all horns and heart. Under

a microscope, bacteria blooms readily, tiny mansions

of the self. Who am I to multiply? My grandfather

gathers chickens by the feet, wings flapping. If you

squint hard, he looks like a butterfly. In the near

future, I heard the continents will connect.

When we turn to each face other, it’s a choice.

(excerpted from Overpour with permission from Action Books)