It’s like wearing a swagger on your face. If you’ve got a mustache, you’re someone to be taken seriously.

Mustaches are so serious in my part of the world that people have been killed over them. In Pakistan, forcibly shaving another man’s mustache is considered an act of unmanning. One so serious, it must be avenged.

There’s a widely believed story about our outgoing president, Asif Zardari. The story goes that a rival politician once held him down and forcibly shaved off half his mustache. Weeks later, according to one version of events, Zardari had this politician assassinated as payback.

“Moochh nahin to kuch nahin” is a common saying in Pakistan–an old wisecrack or proverb, I don’t know which, and neither does Google. But basically, it means this: without a mustache, you’re nothing. A man of no consequence.

And that’s what mustaches are about in many parts of the world–manliness. It’s like wearing a swagger on your face. If you’ve got a mustache, you’re someone to be taken seriously.

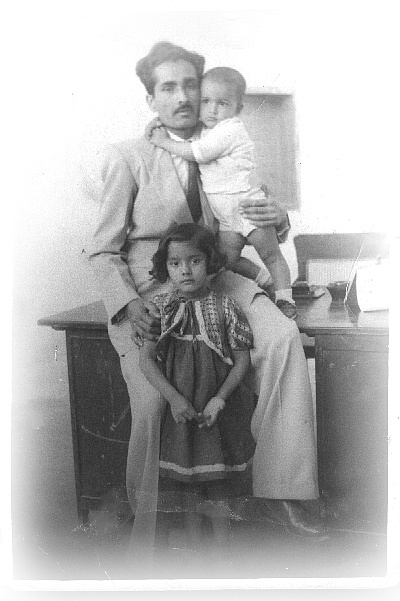

My mother remembers a shiny pair of scissors that my grandfather used to trim his facial hair. The children were forbidden from using them. If he even suspected they’d touched the scissors, there was hell to pay. I can’t imagine my soft-spoken grandfather getting worked up about anything. But, as my mother says, the “Moochh” is a very touchy subject.

You don’t touch the Moochh.

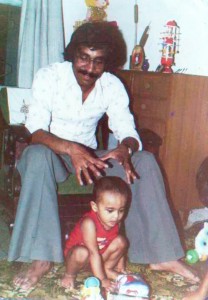

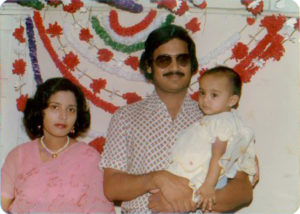

Boys grow them as soon as they can in Pakistan. My father is one of six brothers, and they’ve all had mustaches at one time or another. My mother’s brother and her many cousins have also embraced the Moochh. In Pakistan and most of South Asia, the growth and care of mustaches is still a male rite of passage. Scissors, trimmers, waxes, special conditioners, and combs are all part of a grooming ritual considered the exclusive domain of men.

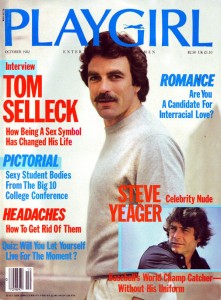

And once upon a time, here in the US, the mustache was also a symbol of masculinity. Think Tom Selleck or farther back, Clark Gable.

That era died out in the 80s and has only recently made a comeback. In some parts of Brooklyn, mustaches are an ironic homage to that era when people still grew them to look good.

Now we throw mustache parties and bake mustache-on-a-stick cookies. We encase our iPhones in mustache covers. We nod our heads along to electronica spun by DJs wearing giant mustache masks. In Bushwick, Gowanus, or Clinton Hill, handlebars, walruses, and fu manchus have become as common as artisanal kombucha.

But mustaches are still serious business for Pakistanis, and for a lot of brown people. Come out to where I live in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and check out the evidence. The men on my block–many of them first generation immigrants from Central and Latin America–sport facial hair as a matter of course, and are clearly proud of being able to grow a mustache. No irony needed—or intended.

Open City contributor Eli Chen recorded these “mustache meditations” in Sunset Park and Chinatown.

Mustaches are that swagger on the face that everyone sees right away. And, just like emotionally wrought Bollywood musicals, they’re not meant to be ironic or camp.

…mustaches are still serious business for Pakistanis, and for a lot of brown people. Come out to where I live in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, and check out the evidence.

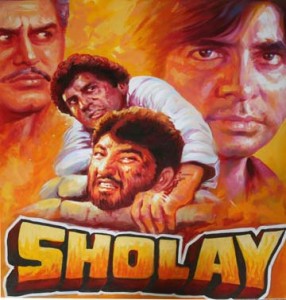

My favorite of those un-ironic musicals is Sholay, the 1975 curry western, a classic of Indian cinema and the ultimate buddy movie.

Six or seven years ago, I attended a special screening of the movie at Lincoln Center. At first, I was surprised to find I was one of the few South Asians in the audience, but then I remembered that Bollywood was recently cool in America. I was glad Sholay was going to be part of this trend. Fans, like me, know all the lines by heart.

But soon after the movie began, I realized many of the audience members weren’t really there to appreciate a classic. They laughed, not just at plotlines lost to bad subtitles, but all the way through. The platonic love between the two male leads is expressed clearly. I guess the emotion between them came across as kitschy.

Perhaps earnest masculinity — like the friendship in Sholay, like big twirly mustaches can only be enjoyed as camp, or it becomes uncomfortable.

I’ve got nothing against anyone growing facial hair because it looks good, or as a fashion choice. What’s troubling to me is what’s behind all this mustache hoopla. It’s what I heard in the laughter in that theater. The insistence on irony over earnestness.

As if it’s too embarrassing to express sentiment as honest and straightforward as the hair on your face.