Vintage American country-western music helps Indo-Guyanese express ineffable heartbreak, spirituality and political emergence.

March 13, 2015

“During our time we were starved for entertainment. Starved,” said Ramesh Kilawan. Ramesh, his daughter Kamelia, and I sit around their kitchen table on a cloudy Sunday afternoon.

We start off round robin on growing up Guyanese and being exposed to country-western music. “I grew up in a multiracial society: Black and Indian,” Ramesh tells me. “This form of music tends to bridge the racial divide. Because of that, that music. Music just put them together because they enjoy the same thing,” Ramesh says.

In the Guyana of the 1960s and 1970s, when Ramesh was a young man, listening to commercial film songs in Hindi was one way many Guyanese identified with their Indian heritage. But these songs shared airspace on the radio and in the cinemas with country-western music, and the latter had just as strong a hold on the imaginations of Guyanese listeners. “Being young at that age and being English spoken I could identify myself more with that than the Indian music,” said Ramesh.

Hearing our grandparents sing a song like Connie Smith’s “Tiny Blue Transistor Radio” word for word is a common occurrence. But I hadn’t realized that outside our community, the Guyanese affinity for country music might seem culturally dissonant. Not until I found myself on Liberty Avenue with a group of Open City fellows in October.

When we walked past Anjee’s, one of the first established puja shops in the neighborhood, a couple of those in the group stopped next to an older gentleman selling cricket balls, bats, and CDs. They were puzzled by the song emanating from his boombox, Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head On My Shoulder. To me, the music was as natural a part of that tableau as the box of multicolored cricket balls or the tiny murtis of Lakshmi and Saraswati. But when the fellows asked how Guyanese became so interested in country music, I realized I had no idea how this cultural preference developed.

What draws everyone to the sad love lyrics and the droning voices? To the twanging guitars? To the singers of classic country? Modern country music singers like Shania Twain are not as popular as the more classic figures. The songs from the 1940s through the 1970s are the ones one can hear on a walk down Liberty Avenue. These have withstood the years for an older generation of Guyanese, though perhaps less so for younger generations.

To me, [Paul Anka] was as natural a part of that tableau as the box of multicolored cricket balls or the tiny murtis of Lakshmi and Saraswati.

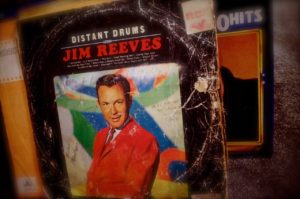

I begin by mining my own memories of country songs. I found that particular songs brought back images of my grandfather closing his eyes, wrapping his fingers around his glass of scotch, singing along with Jim Reeves, or the sound of my uncle wailing the lyrics to Paul Anka’s “Put Your Head On My Shoulder” on a balmy summer night.

My first memories of music are tied to the birthday parties and backyard jams that litter my childhood. Music, dancing, endless rounds of dominoes, stiff drinks, dancing, and tall tales are the ingredients to a successful Guyanese backyard jam. The music varied from Hindi film songs to reggae classics, calypso and chutney, but always culminated with Jim Reeves’ clear voice or Dolly Parton’s sassy lyrics or Slim Whitman’s country charm. During my conversation with Ramesh, I tell him of my uncle’s wedding and how critical it was to my mother to hire a DJ who agreed to devote a solid hour of the night solely to classic country and oldies songs. A “Chutney Bacchanal” followed by “Stand By Me” sort of event.

Mining my memory, I found that I could sing a line or two of the choruses of these songs, that the melodies rose up from the deeper recesses of my mind. But I did not find facts or context. Talking to other Guyanese, especially my own relatives, about this musical taste proved just as difficult. To them, there was no question to be answered, no grand analysis to be done of their preference. Still, they couldn’t deny that many of the country music classics mapped their experiences coming of age.

The Guyanese love affair with country music, like much about Guyanese history and culture, has left few traces in the archives and in institutionalized memory. Chutney, tan-singing, chowtal, tassa drumming, and bhajans are better documented by scholars and journalists. To trace the origins and contours of this particular love affair, I had to scout out the occasional newspaper reference, blog post, and the memories of other Guyanese around me.

The Guyanese love affair with country music, like much about Guyanese history and culture, has left few traces in the archives.

Before I could understand the appeal of the music, I had to think about the trajectory of the songs. How did they come into the listeners’ lives? One major vector for country music into Guyana was radio. The Guyana Broadcasting Corporation, established in 1929, put out shortwave broadcasts two hours a week. And starting in 1951, Radio Demerara’s notably diverse Sunday schedule shaped the musical tastes of the time, and possibly had a deeper effect than the BBC and colonial government programs that populated most of the station’s airtime.

Programs included: Subha Kaa, Taraana, What the Bible Says, BBC News, Sports Reel, East Meets West in Music, Muslim Religious Programme, Country and Western, and Music from Africa. East Meets West, hosted by Ayub Hamid, in particular was an important influence, the country’s first hybrid music radio show. “East Meets West. You know,” Ramesh remembers fondly, “They have one Indian song, one English song and the English song is the country-western.”

Hamid’s show sharply contrasted other music shows that came in from neighboring Suriname and were heavy on Hindi film music. “So really, a young man like me at that age, I’m dying for entertainment. Everybody’s blasting Radio Radika and Radio Rani. Indian music! And I want to hear ‘I love you, darling!’ I wanna hear ‘I’m a romantic!’ ‘I’m young!’ Yuh know? But the people talking Dutch and playing Hindustani music,” he said.

Mike McGraw agrees that some of country’s appeal came from how the style crossed cultures and oceans. McGraw, director of marketing at VP Records, an independent record label and the world’s large distributor of reggae music, was part of the team who produced Reggae’s Gone Country, an album featuring reggae artists covering classic country songs.

“In the evening you could pick up shortwave AM and for some reason at nighttime the signal travels much farther. There was a radio show called Randy’s Radio out of Tennessee that did country music and blues, right, back in the 50s and you could pick it up all the way in Jamaica,” said McGraw. “So a lot of the country music is from this program. And my father, who grew up in Ohio, used to listen to this same program at nighttime because just like it could travel down to Jamaica, people all the way up north, as far as Cleveland, could pick it up, as well.”

The songs lived beyond the radio, as well. My grandmother would clip out record ads in the newspapers, scrapbook the clippings, and buy new records as they were released. Jukeboxes, what some called “big punch boxes,” and gramophones also helped spread the music. And the cinema was a common place to get a country music fix. My grandfather told me that before screening Spaghetti Westerns at the cinema, the projectionist would spin country music songs.

My grandfather and Ramesh grew up in two very different Guyanas, but what they have in common is the important role the English language played in shaping how they understood their cultural identity as they came of age. For my grandfather, English was a symbol of progress, of modernity. For Ramesh, it represented the gap between Indians who migrated to Guyana as indentured servants and their children and grandchildren, a split in identity that developed even before much of Guyana’s population migrated out of the country.

The first generation of Indians that the British brought to Guyana were recruited from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and other South Indian provinces; they spoke Hindi, Bihari, Bengali, Punjabi, Tamil, Telegu, Malayalam and other languages. Once on the plantations, these merged into one dialect, adding to the already rich and complex linguistic environment in colonial Guiana. But this creole was not entirely transmitted to the next generation.

Country music’s English lyrics appealed to a generation of Guyanese who had little working knowledge of the languages spoken on the sugar plantations and rice fields. “You understand the lyrics and the lyrics made a lot sense,” my uncle Eddy tells me. “Because it told a story. All these songs told a story. With Indian songs, there’s a story, but we don’t understand it.”

I hadn’t thought before of these linguistic divides. Hindi commercial film songs are quite popular within the Guyanese community today, and dozens of shops lining Liberty Avenue specialize in selling and renting the latest Bollywood blockbusters and albums. But clearly country touches a spot that filmi music can’t.

“All these songs told a story. With Indian songs, there’s a story, but we don’t understand it.”

And it’s not just the language of the lyrics, but the stories they weave that appeal. I’ve always thought of country songs as sad stories, sad stories with melodies that creep under one’s skin and catchy choruses that stick to memory like honey. Lyrics and voices that evoke stories from listeners. And stories hold an important place in Guyanese culture. A popular greeting among close friends and relatives is “What the ‘tory say?”

Many of Ramesh’s favorite country songs, for example, called back stories of specific events in his life. Ramesh heard Sue Thompson’s “Sad Movies (Make Me Cry)” whenever his aunt would visit and sing it. The song tells the story of a young woman who discovers her boyfriend’s betrayal in a dark movie theater. Ramesh’s aunt used the song to express her anguish about her own heartbreak. “And she went into a rage and she throw kerosene on herself and scratch a match,” he said.

The song is all about hiding deep pain, about veiling our sadness and displacing the source of such emotions. “I love this song because there’s a great meaning. She walk in the cinema and saw her lover kissing somebody else. And she went home and start to cry. And her mother ask her what happen. She says sad movies I’m crying for. But it’s not sad movies,” Ramesh said.

The sad stories and heartbreak are connected to all kinds of major life events. My grandfather connects Hank Locklin’s “From here to there to you” to a vivid memory of the longing that comes with friends separating. But I knew that the song, had another story, a hidden meaning.

“I had been leaving to go to England,” he said. “And it is as though, it was a kind of farewell, as we got together, it was a group of us and that one was just popular and appealed to us. And as the thing goes, we were leaving. And we wanted whoever was near and dear to us, we wanted them to know how we felt.”

What he left out from this version of the story is a young woman he knew before my grandmother, a special someone he wanted to express his feelings to through Locklin’s song. I imagine him as a young man, at a busy port, saying goodbye, perhaps leaving an address for her to write him. I imagine him humming “From here to there to you” as the ship starts across the Atlantic and the distance between them grew.

The narratives Guyanese listeners heard within country music were not just about separation, but also about connection. For my grandfather, the pantheon of classic country western singers is incomplete without Jim Reeves, an American country music singer who became popular in Guyana in the 1960s. His songs were deeply personal, but more spiritually oriented. His voice is clear, distinct, overpowering.

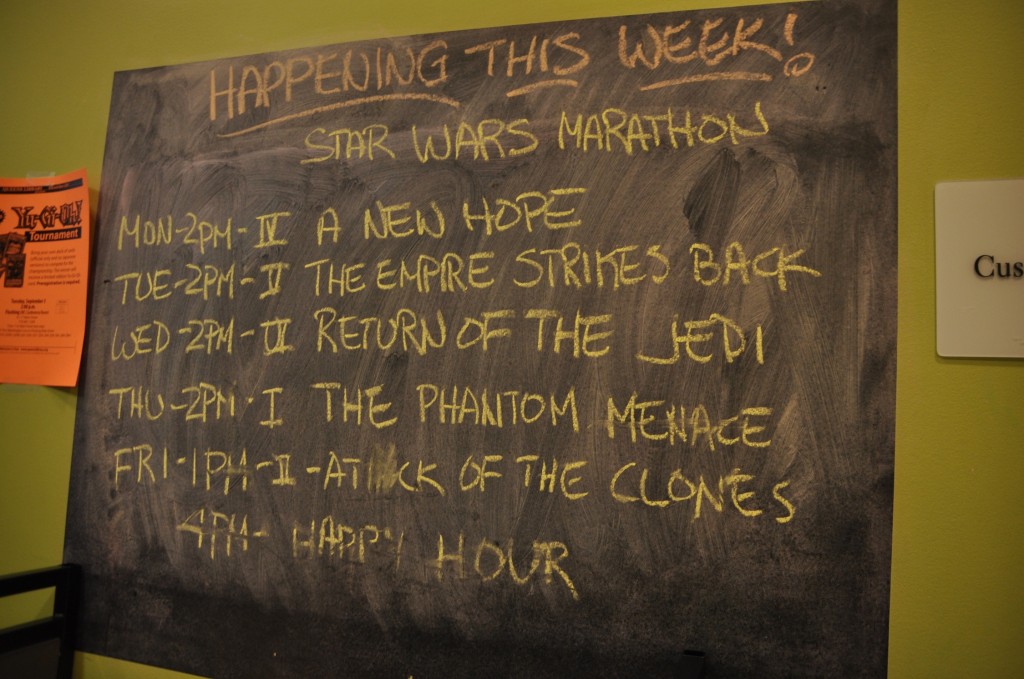

As a child, I thought of waking up to Jim Reeves on a Saturday morning as a form of punishment. There is a certain sharpness and purity to his voice that has always unsettled me. Album covers depict a clean-cut young man in khaki pants, a shirt and tie topped with a cardigan, and this good boy-next-door image kept me from becoming a fan. But it was a definite part of the appeal for listeners from Ramesh’s and my grandfather’s generation.

Reeves’ angelic persona provided a narrative of spirituality that crossed faith lines. Kamelia’s grandmother personally requested her cousin, a converted Pentecostal Christian, sing Jim Reeves’ “This World is Not My Own” and “I’ll Fly Away,” two songs which speak of the impermanent nature of human existence and transient quality of the soul. Both women found a common spiritual touchstone from different beliefs. “My grandma was Hindu and she loved bhajans,” said Kamelia. “But these songs really meant something to her. So she made sure that those songs were played in addition to other Hindu rituals and practices and bhajans.”

The stories the songs weave together express the ineffable, but they can also connect to more worldly concerns. It doesn’t take long for my conversation with Ramesh and Kamelia to go down the road of politics, race, and identity in Guyana — a conversation which spills over into the Guyanese diaspora in Richmond Hill, Queens.

The conventions that make the genre so expressive of unspeakable emotions – allusion, ellipsis, letting timbre and twang do the heavy lifting — also make it a perfect vehicle for political thought and gave voice to emerging collectives. Take Guyana’s Singing Cowboy, Nesbit Chhangur. Born in Berbice, Chhangur was one of Guyana’s first recording artists. His song “A Guianese Lament (Tain Public Road)” features somber lyrics set to a simple beat, a direct response to post-independence race riots calling for an end to racism between Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese. He sings: “Out of blackness comes the bomb/When will our hatred end/and race work with race together as friends.”

Today, the songs still live in the dusty record holders of some Guyanese families, or in that box next to the cricket bats and murtis on Liberty Avenue. They have travelled across yet another ocean. While I may not listen to Paul Anka or Dolly Parton on a regular basis — I save them for deep heartbreak and traumatic subway commutes — the songs are still a large part of how I understand my childhood and growing up in the grey space between Guyanese and American cultures.

But these songs also provide a younger generation of Guyanese-Americans a connection to the youths of their parents and grandparents. For me, I know that whenever a country record spins, a bit more of my relatives’ pasts is unsilenced. The songs open up space to talk about their school day romances and adolescent angst.

When, over bitter coffee and thick pancakes at the local IHOP, I talked about this piece to a close friend who also grew up in a Guyanese household, I was surprised her enthusiasm and nostalgia. She also had trouble explaining this love affair to people outside the community, but agreed that it existed and persisted, in traces at least, in our own generation. We burst into song, moving fluidly between “Sad Movies” and “Send Me the Pillow That You Dream On.” In the end, it’s the love that need not spell out its reason.