A novelist recalls her childhood steeped in Chinese radio plays heard on the Singapore airwaves.

May 6, 2015

[Editor’s note: As we experiment with publishing great reads from cities beyond New York, this beauty came across the transom, and, well, we couldn’t resist.]

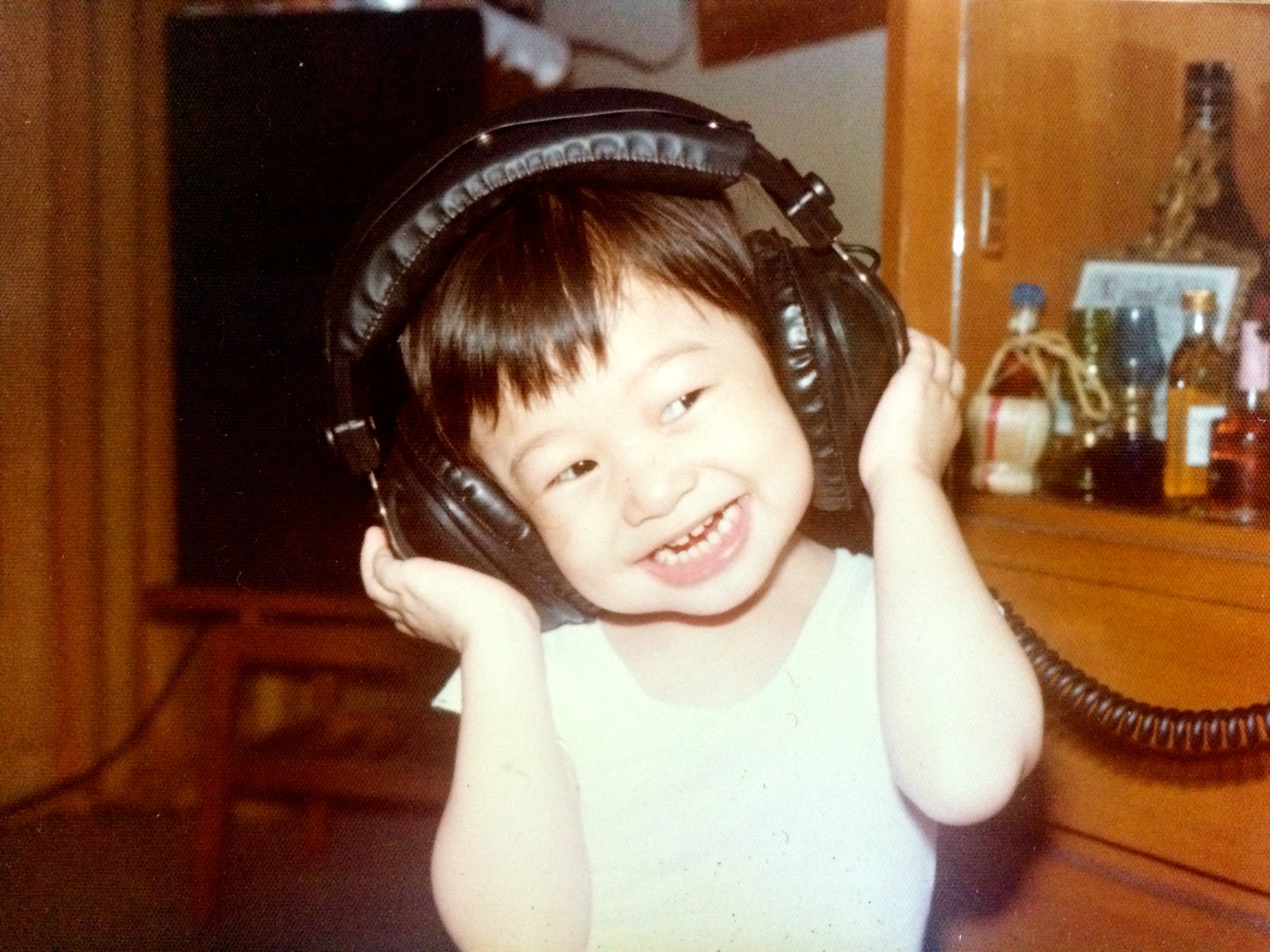

Because I write novels, people often say, “You must have been a bookworm as a kid.” The truth is more banal. I did not read books; I heard stories. I was born in Singapore in 1974. Books were expensive, but radio was (almost) free.

Before elementary school, I didn’t read. I didn’t write. I didn’t even speak much. I just listened. My grandma’s kitchen radio was tuned to only one channel: Rediffusion. From the 1940’s to the 1980’s, this UK cable radio service ruled the airwaves of many British colonies, Singapore included. Make no mistake: we didn’t like it because it was British. We liked it because the Brits were smart enough to hire Chinese DJs, scriptwriters, and producers to create original Chinese language content to appeal to the local populace. And not only in Mandarin, either, but in all of the southern dialects commonly spoken by Chinese Singaporeans: Hokkien, Teochew, and Cantonese.

Make no mistake: we didn’t like it because it was British. We liked it because the Brits were smart enough to hire Chinese DJs, scriptwriters…

Headquartered in the UK, Rediffusion was a subscriber-based cable radio service which “re-diffused” content over a wired network. Singapore’s radio reception was poor in those days: few people bought normal radio sets. Cable radio was a great alternative. It was cheap and practical. For SGD $5 a month, the company gave you its own branded speaker. It needed no electricity, which explains why my family left it on all day.

It is difficult to picture this type of old technology now, but it was very popular back then. According to a UK Rediffusion fan website, “the Chinese [in Singapore] are very fond of electrical appliances …The power stations were badly overloaded and blackouts were frequent. At the main Rediffusion building a standby generating plant was run every evening from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. to relieve the municipal supply of the 16-kw load.” The website documents that cable radio wires were painstakingly thread in and out of Singapore buildings and regularly serviced by Rediffusion employees in distinctive company vans.

Teochew has six tones, Hokkien, seven, and Cantonese, nine. This pure, Tang dynasty sound permeated my childhood because of radio.

Online sources say that Rediffusion reached a peak of 200,000 subscribers in Singapore in the 1970s. Singaporeans of the baby boomer generation recall today that they didn’t even have t.v. – they just sat by their ‘radio’ and listened to stories. Which is exactly what I did in the 1970s, since I didn’t have to go to school yet. I consumed an endless array of storytelling on Chinese dialect radio. It was a glorious education for a novelist.

Mandarin, China’s official tongue, is a language of relatively recent invention. With only four tones, it is the new kid on the block. The southern dialects are ancient. Linguists say that they are more akin to what Chinese people spoke thousands of years ago. Teochew has six tones, Hokkien, seven, and Cantonese, nine. This pure, Tang dynasty sound permeated my childhood because of radio.

The first day at school, teachers addressed me in English and Mandarin. They were cold, alien tongues, so different from soft, undulating Chinese dialects.

Rediffusion’s single Chinese channel broadcast in different dialects throughout the day. Although some of the dialects, such as Teochew and Cantonese, are mutually unintelligible, I ended up understanding all of them as a child. My generation was one of the last beneficiaries of this liberal language policy.

1980 was a critical year in my life. I had to tear myself from the comforts of my Grandma’s home and go to elementary school. The first day at school, teachers addressed me in English and Mandarin. They were cold, alien tongues, so different from soft, undulating Chinese dialects. Stunned, I burst into tears. I wanted to leave the room. Grandma recalls taking me to school everyday as if “she was a pig being led to slaughter.”

That same year, the Singapore government legislated to phase out all Chinese dialects from national broadcasts. By 1982, television and radio could only be programmed in four official languages: English, Mandarin, Malay and Tamil. That Tang dynasty sound came to an abrupt end. But the genie was out of the bottle. I had discovered a rich auditory heritage—and an addiction.

Radio.

I grew up with six uncles in my grandmother’s tiny apartment. One of the household’s most important members was set on its own shelf, mounted near the ceiling in the kitchen, for maximum broadcast potential. Our Rediffusion speaker was the size of a bread box, with a fake wood veneer and two black knobs. It was always horribly dusty, because nobody ever got up there to clean it. There was never any need to touch the device, since we never ever changed the channel. Why would we listen to imported British shows in English, when we had serialized Hokkien radio soap operas, full of shooting guns, pattering feet, dramatic orchestral swells, and sobbing revelations?

Our Rediffusion speaker was the size of a bread box, with a fake wood veneer and two black knobs.

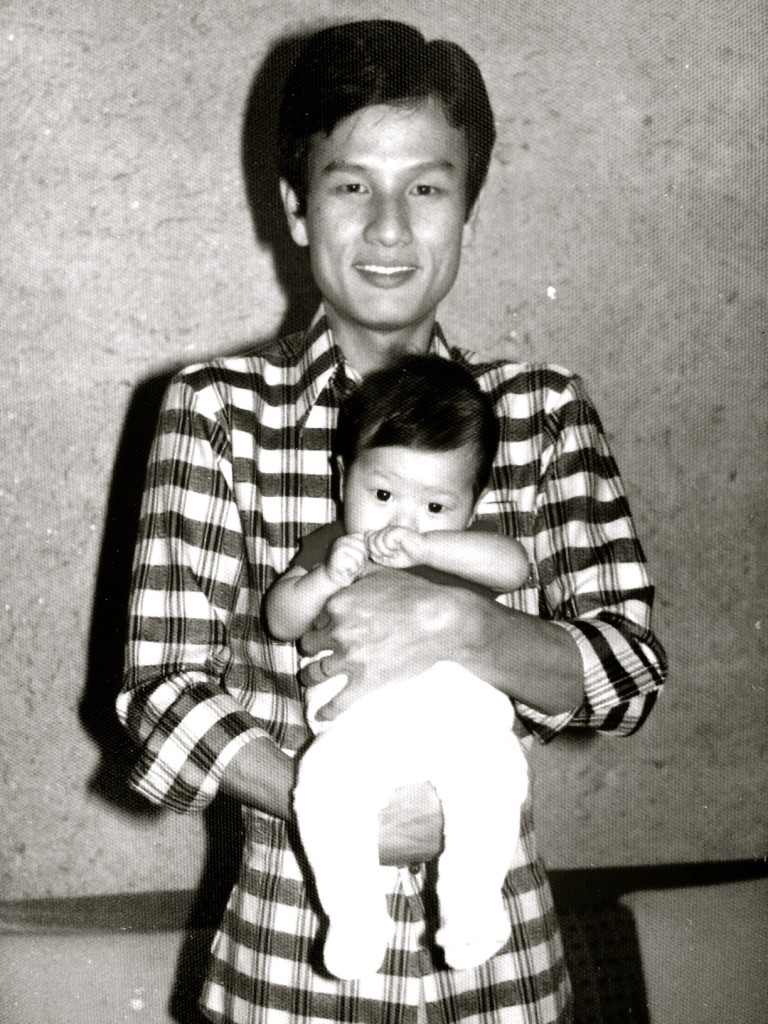

Grandma’s apartment was under 800 square feet. At its peak, it housed eight family members and a cottage industry. One of my uncles was self-employed. He made Teochew fishballs and fish dumplings for restaurants. (This was a solid Teochew credential, akin to being a baker of bagels in a Jewish neighborhood in New York.) My aunt and uncle made everything by hand. It was artisanal and time-consuming. Like many Chinese workers at the time, they labored while listening to Rediffusion’s Chinese radio dramas. Just like you would listen to audiobooks today on your commute.

* * *

Imagine being three years old on a blisteringly-hot afternoon in tropical Singapore, one degree north of the equator. We didn’t have A/C. I didn’t do well in the heat and spent most of my childhood practically catatonic, lying like a cat on the cool tiled floor, listening to Rediffusion while my uncle and aunt folded dumplings.

You couldn’t avoid Rediffusion even if you tried. The sound permeated every corner of the small apartment. As they worked, my relatives kept up a running commentary on the radio play. It was like Mystery Science Theater 3000. My uncle spoke Teochew; my aunt, Hokkien. Thankfully for their marriage, these two dialects were mutually intelligible.

“She’s going to marry the rich doctor,” said my aunt.

“Huh? I thought she’s going to run away with the university student?” said my uncle.

“I guarantee you she will change her mind in this episode.”

“Women are so fickle!”

“Not fickle! Filial! She will listen to her father and marry the rich doctor. And you know what? I bet she’s already pregnant with the university student’s child.”

“No way!”

“I’m telling you, these stories always turn out like that. Otherwise there won’t be a story to tell. That’s how they drag it out for so many episodes.”

They paused to listen to a sudden revelation, scored by violins. The heroine’s sobbing voice filled our kitchen. She confessed to her rich doctor suitor, “I have something to tell you. My heart is set on marrying you, but what’s done cannot be undone.”

“Hah!” my aunt cried out in triumph. “Told you! She’s pregnant!”

The heroine whimpered, “I am afraid the raw grains have long been made into steamed rice.” It is a famous Chinese phrase, reserved for confessions of pregnancy from premarital sex. Even I knew that. My aunt and I giggled wickedly.

“But whose child is it?” My uncle had floury hands. He tossed some flour on the dough and applied the rolling pin vigorously. He made wrappers for the dumplings. From these skinny arms issued forth, every day, armies of dumplings – rows upon rows of dimsum crafted from scratch. Although made by hand, they were all miraculously identical in shape, angle, and size. He was a professional.

He made wrappers for the dumplings…armies of dumplings – rows upon rows of dimsum crafted from scratch.

But here the play ended. Each episode always ended on a cliffhanger. The dramatic closing theme came on – pum pum pum paaah! – then the announcer. We were all exhorted to tune in at the same time tomorrow to find out what happened (and whose child it was).

My uncle was now slicing dough into tidy squares with a giant cleaver. He looked over his shoulder. “Goodness! Wena! What are you doing, child?”

I was rolling over and over the kitchen floor, busily crashing into furniture.

“Guess,” I murmured.

“She’s mad,” said my aunt crisply, not looking up from her worktable. She stacked dumplings neatly in plastic boxes. With floury hands, she stapled them shut. Later, my uncle would deliver them to his clients by motorbike.

Now that I had a real audience, I got up, walked over to one end of the kitchen, fell down limply and began my roll all over again, this time in slow motion, for their benefit. “Aiya!” I pretended to cry. “Aiya – aaaaa.”

“Look at her, just look at her!” roared my uncle, pointing his cleaver at me. He had a habit of brandishing the formidable weapon to underscore a point. “Are you sick, child?”

“I am falling…down…” I wailed softly, pitifully. “…a flight of steps…guess who I am? Guess…”

Waving his cleaver wildly in the air, my uncle yelled for Grandma to come to the kitchen. “Hurry up or you’ll miss it!” he cried.

My Grandma came into the kitchen.

“Look!” roared my uncle in indignation. “What’s wrong with your grand-daughter?”

“Goodness! Get up, Wena, the floor’s dirty!” said Grandma.

“She’s possessed,” said my aunt.

I paused in mid-roll to explain. “I am that girl from the Cantonese radio story this morning. Remember? She was pregnant with a big belly, and she was fighting with her husband, and he pushed her accidentally down the stairs. By the time she rolled to the bottom, she had lost her baby. Like this – aiya-aaaaaa – ” I resumed my roll in precisely-crafted slow motion across the floor, so that they could all relish the full effect. I got flour in my hair for my pains.

Grandma said, “You guys really shouldn’t listen to that rubbish on the radio. Look at what you’ve done to her!”

I resumed my roll in precisely-crafted slow motion across the floor, so that they could all relish the full effect. I got flour in my hair for my pains.

On the radio, a new show had already begun. A Teochew lady storyteller with a pleasant, genteel voice. A multi-part story about the Emperor of China and his concubines. Court intrigue. The villain: a corrupt eunuch who sought to frame the Emperor’s favorite concubine, Sio Xiang.

“What happened to Sio Xiang in the last episode?” asked my uncle, julienning carrots into tiny matchsticks with the same giant cleaver. Tuk, tuk, tuk, tuk, tuk. Chinese chefs only had one knife, which they used for all tasks, including pointing at people for emphasis. The carrot slivers would be inserted in a type of dumpling called “fish scroll”, so named because they looked like ancient Chinese books made of bamboo splints threaded together. “Did the Emperor believe in her innocence? Or has she already been executed?”

“No idea, I don’t follow this one,” said my aunt. “Old classical stories are boring.”

They had ceased paying attention to my antics during the brief intermission. The new story was starting.

“Wena, do you know what happened to Sio Xiang?” asked my uncle. “Eh? Is she dead or alive?”

But I had gone back to my heat-exhausted, catatonic state, lying on a cool patch of the ceramic tile floor, listening to the melodic sounds of Teochew cascading from the radio above my head.

“Your Majesty!” cried the heroine inside the dusty speaker. “I am innocent! Please do not listen to the Chief Eunuch’s wild tales! Truly, you have wronged me!”

“Huh! I must have been blind to have trusted you! Guards! Take her away at once!”

Screams and shouts as the concubine is dragged away.

My uncle shook his head at the cutting board, “She’s a goner.”

“There’s always a deus ex machina,” said my aunt. “You’ll see.”

* * *

Rediffusion Singapore ceased operations in 2012 after 63 glorious years. The brand name was acquired by new owners and operates today as a digital Chinese media platform. Today, the Singapore radio scene resembles that of commercial radio in any other developed country. There are dozens of channels, mostly full of crazy ads and contemporary pop. Radio storytelling, Rediffusion style, is a thing of the past.

Stories are meant to be enacted, spoken aloud, and debated. They should surround us and be exchanged between us, like the very air we breathe.

Singapore no longer prohibits Chinese dialect broadcasts. I can see a new generation of young writers and performers creating new content on Rediffusion to bring back some of the glory of old. Many of the old Rediffusion DJs are still around. Resurrecting Chinese radio plays would be very retro-cool, and many Singaporeans would welcome it. However, it would just be an arthouse project. Listeners and their expectations have moved on. You can’t turn back the clock, and Rediffusion cannot play the same role in Singaporeans’ lives as it once did.

Still, people love to hear a good story performed well. That’s where stories really want to be – not fixed in books like dead butterflies pinned on a card, but flitting about in that borderless ether, drifting into our homes, coloring our humdrum existence. Stories are meant to be enacted, spoken aloud, and debated. They should surround us and be exchanged between us, like the very air we breathe.

When marketing the brand name “Rediffusion” to the Chinese, the British company tried to come up with a good translation. They finally settled on “li de hu sheng” ????. Beautiful Exhalations. I couldn’t have said it better.