Harmoniums are all over South Asian music. But they also connect Guyana and Punjab spiritually

December 22, 2014

It’s the third time I walk up to Mindra’s house, a nondescript white house on a quiet street off Jamaica Avenue in Queens. Mindra greets me at the door, wearing a t-shirt, sweatpants, and a warm smile, and immediately starts chatting me up.

Filled with anticipation, and a cup of sugary chaa I gulped down at the gurdwara down the street, I try to pay attention and make conversation. But all I can really think about is: did he really fix my harmonium?

The fact that my harmonium is broken is more than inconvenience for me as a working musician. The air-powered keyboard instrument, with its droney, rich, double reed sound, has provided me access to spiritual grounding since my childhood. My malfunctioning instrument is practically blocking my feeling of connection to the Divine.

All I can think about is: did he really fix my harmonium?

Mindra Sahadeo, a harmonium expert, informed me that my harmonium has “major issues.” He texted me half a dozen photos of the warped, sloppily carved wooden keys—which always stick when I played them—and the nasty crack beneath the keyboard to show me the scale of the problem. A few weeks ago, another, better known harmonium repair person in Manhattan told me it was a lost cause and not worth fixing.

As we walk through the front door of his house, I see one harmonium in a soft case someone just dropped off. Mindra looks at it and laughs, “That one’s really busted up.” There’s another in a large metal box that looks like it weighs 100 pounds—a recent shipment from India.

We walk up one flight of carpeted stairs into his apartment, and his mom greets me, saying “Sat Sri Akaal.” The living room is small and simple, carpeted with fluorescent lighting. At one end of the room, there’s an altar on a table with a dozen colorful pictures of Hindu Gods. At the other end, eight or nine harmoniums of various sizes and colors are piled up. One of them is mine. It looks a little shinier than before, but I’m nervous. Did he really fix it?

He opens the latch on the bellows of the chocolate brown wooden instrument, and plays a few bars of some simple melodies. He pushes it toward me, and I fumble along the keyboard, in amazement that none of the keys stick. It feels like a different instrument. He tells me it’s a good harmonium, but if I want to record with it, I should get think about getting a new one, not necessarily from him. He says I can probably sell mine for a few hundred dollars because, “White people like these kind of harmoniums.”

I first met Mindra in late August in the midst of a harmonium crisis. I had a gig coming up, debuting a new project in which I play harmonium, something I hadn’t done on stage in years. As we rehearsed, it became clear that my harmonium wasn’t going to cut it. The week before I met Mindra, I had come to Richmond Hill in search of a new one. Given the centrality of the instrument in Sikh spiritual-musical practice, I had limited my search to three gurdwaras, and struck out each time.

A Craigslist ad sent me on another fruitless expedition on the A train, from Lefferts Blvd. to 168th Street in Washington Heights, where a Dominican former yogi showed me a barely functional harmonium in the dingy basement of a hair salon he owns. I got right back on the A, Brooklyn-bound, defeated.

A fruitless expedition on the A train took me to a Dominican former yogi and the dingy basement of a hair salon.

On the eve of my gig, I tried out some Google searches, and one of the results led me to a Facebook page for “Mindra’s Harmonium Sales and Repairs.” The location was listed as “Queens, NY.” How had I not found this place in my frantic search a week before? Mindra sent a cheerful reply to my message, accompanied by photos of beautiful instruments, saying he sells and repairs harmoniums out of his apartment in Richmond Hill. We set up an appointment for me to check out what he had.

I wasn’t quite ready to drop the cash for a new instrument; Mindra assured me that he could fix the harmonium I had. So I borrowed a friend’s harmonium for the gig and put mine in Mindra’s hands, hopeful he could coax a little life out of it.

Harmoniums have become almost entirely identified with music forms of the Indian subcontinent—from classical to Bollywood—but its origins are colonial. The harmonium was originally a European instrument that arrived in India with the British in the 18th Century. The European version of the air-powered keyboard instrument required sitting up and pumping air with foot pedals. Classical and folk musicians in South Asia, however, generally play sitting on the floor, so the harmonium was adapted to be played that way, as if it were a reclining accordion, with one hand pumping the bellows and the other playing the keys.

Growing up in a Sikh household in Charlotte, North Carolina, the first instruments I learned to play were the harmonium and the tabla. Sikh devotional music—Gurbani kirtan—is most commonly played on harmonium, so as kids, we learned some basic shabads (devotional songs) on the instrument. Growing up, we had two harmoniums, and a set of tabla in my house, which my brother and I played. We learned at annual Sikh camps and performed regularly at the monthly makeshift gurdwaras that community members set up inside their homes to substitute for the absence of an actual gurdwara in Charlotte.

While I am primarily a trumpet player now, playing harmonium brings me a sense of comfort, even nostalgia. It is a direct connection back to what first got me playing music—Sikhism. Not being able to play it with ease for the last few years because of sticking, warped keys was frustrating on a level deeper than I realized at the time—a barrier to accessing one of my longest standing entry points into spirituality.

So my quest to have a functioning harmonium once again felt especially urgent and important. When I sat down to talk with my newfound harmonium savior, Mindra Sahadeo, I quickly began to realize that my relationship (and my Sikh community’s relationship) to the instrument was not so unique.

Playing harmonium brings me a sense of comfort, even nostalgia. It is a direct connection back to what first got me playing music—Sikhism.

In our first phone conversation, I was surprised to hear his Caribbean accent. Mindra told me the harmonium is very popular in the Indo-Guyanese community, and, as in the Sikh community, it is primarily used in devotional music.

Mindra started repairing harmoniums two years ago, after years of playing and singing professionally. “In the [Hindu] temples, lots of the harmoniums are busted and messed up,” he said. “And I always be fingling with them and trying to fix them. This friend, a white friend actually, said, ‘Why don’t you help these people fix them and you can do it like a business?’”

By trial and error, reading up and watching videos online, Mindra became one of just two harmonium repair shops in New York City. He told me the other repair shop tried to hire him last year, but he preferred to continue on his own. “It’s really tedious, you gotta have patience for those skills. Then [in Guyana], I didn’t have too much patience, but now I’m getting some,” he laughed.

Although Mindra is not too far removed from his life in Guyana – he arrived in Queens only five years ago – he was already familiar with New York when he migrated. He traveled regularly to the city for his family’s fabric business. He landed in Richmond Hill because he had many friends and relatives in the area already. His younger sister and his mother soon followed, and they continued many of their family customs in their new home.

Mindra began playing music in the temple as a child—first on dholak, a two-sided hand drum, when he was five, then on harmonium at age six. “Back then before I even had a dholak, I can remember I would be hitting the sides of the wood [furniture] like that,” he recalled, playing a beat on the wooden shelf with his hands.

Like mine, Mindra’s relationship to music started at home. “My mom knows the Ramayana and the [Bhagavad] Gita and plays dholak. My dad was big into Ramleela chanting and Chautal [a form of folk singing during the Holi festival] – big stuff, the Ramleela they called it back in the days. Both sides of the family had all of these links, these spiritual links into music, big time.”

“I guess it was in the genes too,” he added, laughing. His mom, listening in on our conversation, chimed in, “Of course!”

In Mindra’s family, there was no separation between music and spirituality. “[When] I was maybe 4 years [old], we had a routine thing, you know: we came home, you had to bathe, you had to pray, then you had to do yoga, you had to do meditation. Young age man, very young. Everybody had to sit and pray together as one family.” And prayer involved chanting and singing, accompanied by harmonium, tabla, and dholak.

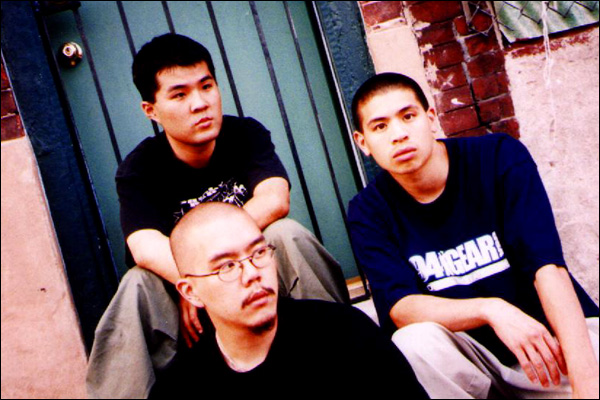

So it’s no surprise that all four Sahadeo children became musicians. His two sisters are classically-trained vocalists, while he and his late brother played harmonium and percussion. His parents called them the Sahadeo Quartet. The quartet performed regularly all over Guyana, including their father’s temple, the Triumph Hindu Mandir, which is now led by one of his sisters. The temple is connected to the Guyana Hindu Dharmic Sabha, which was co-founded by their father and remains the largest Hindu organization in Guyana two decades after his death in 1992.

Mindra and his family continued their deep ties to the Hindu community after their move to New York. Mindra began performing bhajans, Hindu devotional songs, at temples all over Richmond Hill.

But he has also found a spiritual home in Richmond Hill’s gurdwaras. He attends the gurdwara on 118th Street (Sikh Cultural Society) five or six times a week. “It reminded me of home,” he said. When I asked what drew him there, he immediately responded: “Seva. S-E-V-A, bro.”

Seva is a Sanskrit word that means selfless service. For Sikhs, doing seva—in and outside of the Sikh community—is considered a spiritual obligation. Volunteers—or sevadars—in gurdwaras from Punjab to Queens cook and serve meals every day in the langar hall, a community kitchen open to anyone.

“The seva they do there is unbelievable,” says Mindra. “It just sucked me in! My dad was big into seva. Feeding people, that’s one thing he always did. Always on the religious, spiritual holidays, he’d cook—BIG cooking…[and] would get us cooking with him. So these things bring back memories of going to the temple.”

The gurdwara also tapped into Mindra’s passion for music. “I had no idea they had live music in there man!” he tells me. “Amazing, amazing, the music. These guys [the raagi jathas, or music groups, who perform Gurbani kirtan at gurdwaras] are classically trained. The raags they sing are very sad.” His mom chimed in, correcting him: “Touching.” Mindra continued, “Most times they make you cry man. Very emotional in a good way, you know. These guys are absolutely fantastic.”

In the many years I have attended gurdwaras in Richmond Hill, I do not remember seeing any members of Richmond Hill’s huge Guyanese community. I wondered how Sikhs at the gurdwara received the Sahadeo family. Mindra matter of factly responded, “Those guys doing all the seva [in the langar hall] have become our friends!”

Mindra recounted how he and his sister approached one of the raagis—an elderly Sikh man—after they saw him play at a recent visit to the gurdwara. He only spoke Punjabi, so they spoke through a translator. “He didn’t even know [Indian] people [are] living in Guyana. He was like, ‘Where’s Guyana?’ He was amazed. My sister sang a few raags, he was like, ‘Oh my God! Wow!’”

“Those guys doing all the seva [in the langar hall] have become our friends!”

This Sikh musician would also probably be surprised, like I was, to learn that, according to Mindra, most Guyanese households in the area own at least one harmonium. The same can be said for Sikh households. In both communities, the ubiquitous instrument embodies continuity between music and spirituality. We sing, we chant, we meditate melodically, accompanied by the warm, soulful harmonium sound.

Walking down the streets of Richmond Hill, these two communities, living side by side, may often seem disparate—sharing little more than their Indian ancestry and brown skin. But meeting Mindra illuminated a different reality. Bringing my harmonium to Mindra’s shop was more than a business transaction or a meeting of music heads. It was a diasporic connection between Punjab and the Caribbean.

Mindra said, “I should ask to go sing [at the gurdwara] one day. Some day.” I encouraged him to do so and suggested that we go to the gurdwara together. His face lit up with a warm smile, “Definitely bro. It’s home.”