The frustrations and aspirations of the most famous outlaw from Korean pre-modern literature echo a story of modern Korea.

August 23, 2016

The following is edited from the introduction to the new authoritative translation of The Story of Hong Gildong published by Penguin Classics this year.

This Thursday, join us as we celebrate the book’s publication. Translator Minsoo Kang will deliver a talk about his new translation, and we’ll also present short reflections on Hong Gildong by novelists Min Jin Lee and Marie Myung-Ok Lee.

As NPR writes, “Hong Gildong is an iconic figure in the Korean literary canon… He’s the mythic center of a sometimes-delightful, sometimes-unsettling tale, and it’s time the Western world gets to know him.”

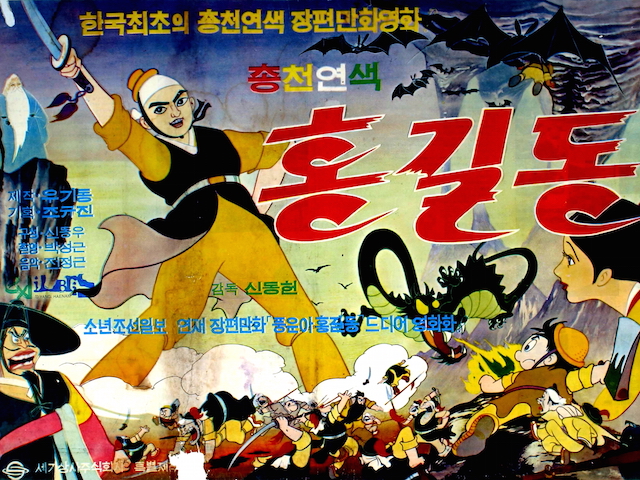

The Story of Hong Gildong is arguably the single most important work of classic (i.e., premodern) prose fiction from Korea, not only in terms of its literary achievement but also of its influence on the larger culture. In the modern era the iconic narrative has been retold, revised, and updated countless times in fiction, film, television shows, and comic books. Even Koreans who have never read the original work in full are familiar with the tale: the illegitimate son of a nobleman and his lowborn concubine, Hong Gildong, leaves home in frustration at the treatment he receives from his family. He becomes the leader of a band of outlaws who dedicate themselves to robbing the rich and the powerful, until finally he leaves the country to become the king of his own realm. Most Koreans can recite the hero’s lament at his condition as an illegitimate child: even though he is a sturdy man of great talent, he is not allowed to “address his father as Father and his older brother as Brother.”

A figure as quintessentially Korean as Robin Hood is English (one could mention other heroic outlaws such as Song Jiang of China, Nezumi Koz? of Japan, Juro Jánošik of Slovakia, Salvatore Giuliano of Sicily, Ned Kelly of Australia, and Jesse James of Missouri[i]), the presence of Hong Gildong in Korean culture is ubiquitous even today. One apparent indication of this is the widespread use of his name as the generic cognomen in the manner of “John Doe.” Instructions on how to fill out forms commonly use Hong Gildong to indicate where one’s name should be written, and the English-language Wikipedia article “Korean Names” features an illustration with “Hong Gildong” in both the hangeul phonetic script (홍길동) and Chinese ideograms (洪吉童).[ii]

Among all the works of fiction from the Joseon dynasty (1392-1897), one aspect that makes The Story of Hong Gildong unique is its protagonist’s status as a secondary son of a nobleman. The hero laments constantly that, although he possesses great abilities, he is prohibited from pursuing his ambitions in the traditional yangban way because of his birth. Later on, he explains to the King of Joseon that he wanted nothing more than to serve him as a loyal official or a general, and that his frustration at being barred from that path is what caused him to leave home and turn to the life of an outlaw. The only work that rivals The Story of Hong Gildong in its popularity and importance to Korean culture is The Story of Chunhyang, whose protagonist is a secondary daughter of a nobleman. The persistent popularity of the two works lies in their ability to make the reader identify with the frustrations and aspirations of the main characters. Readers who were alive when both these works were published would have felt this all the more powerfully, especially the secondary and commoner status people who lived in the deeply troubled time of the twilight of the Joseon dynasty when the established social and political hierarchy fell into severe crisis.

Regardless of the political interpretation that can be made of The Story of Hong Gildong, its central purpose has not been one of ideological advocacy. The moving portrayal of the hero’s frustration as a secondary son, his role as the leader of outlaws, and his challenges against authority figures can all be read as critiques of the status quo. But one must also consider the fact that Hong Gildong’s ambitions are always couched in the traditional terms of desiring to work as a government official. As an intrepid and invincible leader of loyal bandits, he never seriously tries to change the society he lives in, and he ultimately submits to his monarch once he is granted an official position. The Story of Hong Gildong is first and foremost a narrative of entertainment.

The Story of Hong Gildong should be appreciated not only as one of the best prose narratives produced during the Joseon dynasty, but also as the finest example of popular fiction that appeared in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As a product of the final period of the dynasty, the work differs significantly from the moralistic fiction by yangban writers—it is a plot-driven narrative featuring fast-paced episodes that alternate between scenes of high emotion and exciting action. All available evidence points to the fact that it was originally composed in the phonetic hangeul script to accommodate the increasing number of literate common people.

The work’s persistent popularity in the modern era can be explained by its elevation of a neglected secondary son as a great hero. In the history of modern Korea, the people of the peninsula have experienced a series of humiliations from colonization, forced division, and domestic oppression. As a result, a central agenda in the political rhetoric of both North and South Korea has been the recovery of national dignity and respect, oftentimes through massive displays of newly acquired power in the realms of the military, economy, and culture. Starting from the attempt by imperial Japan to convince Koreans that they were inferior relatives who had to be civilized through colonial tutelage, the liberated but soon divided nations felt like they were the bastard children of foreign powers that set their destinies in motion without consulting them about their own desires for the future. As a result, the theme of being disrespected, unappreciated, and underrated by callous and unwise authority figures blind to the emotional needs and the substantial talents of the protagonist has a profound resonance in the Korean psyche. In other words, the Joseon dynasty story of a secondary son seeking to overcome the disadvantages of his background and the oppression of his society in order to prove his true worth as a man, a leader, and a ruler has become the story of modern Korea itself.

From the Introduction to The Story of Hong Gildong, translated by Minsoo Kang, published by Penguin Classics, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Introduction copyright © 2016 by Minsoo Kang.

[i] On the universal figure of the heroic outlaw see Eric Hobsbawm, Bandits (New York: The New Press, 2000), Paul Kooistra, Criminals as Heroes: Structure, Power and Identity (Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1989), and Graham Seal, The Outlaw Legend: A Cultural Tradition in Britain, America, and Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

[ii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean_names.