For outer borough residents and the linguistically isolated, the future is less clear.

November 1, 2012

Manhattan’s Koreatown is open for business, but things are not quite the same. “Let me see…” said the woman who answered the phone at Cho Dang Gol restaurant, speaking in Korean. “It took me three-and-a-half hours to get to work today from Flushing.” When I asked about the rest of her co-workers, she explained, “We are taking taxis and some of us are getting rides, but it is so hard.” Many of the restaurant’s workers lived in Flushing, and even though the restaurant subsidized the taxi cost, she was not looking forward to the ride home. Likewise, a commuter from Bayside, Mr. Lee Yong Nam, told The Korea Times that his Bayside-Midtown Manhattan minivan commute, which normally took 40 minutes, now took four hours.

Another restaurant worker who answered the phone at Kang Suh Restaurant, explained in Korean, “We’ve had power on this block of 32nd Street [in Manhattan’s Koreatown], but the area here is really block by block; some have electricity, some don’t. So it’s been quieter than normal.” However, our phone call kept getting cut mid-sentence, and she explained that phone service had been spotty. After three tries, we ended the conversation.

The manager at Manhattan’s H-Mart, the large Korean grocery in the middle of 32nd Street, snapped at me, “I’m too busy! I can’t answer questions!” and hung up, while at the H-Mart on Northern Boulevard in Flushing, the woman who answered the phone took the time to explain, “We’re ok. But the Long Island and Great Neck H-Mart’s have been affected badly by the storm. You should call them.” The Korean media reported that many Korean businesses in Long Island and parts of Jersey were still closed after the storm due to blocked roads and sidewalks.

Haejung, a recent graduate of Fashion Institute of Technology and a resident of Flushing, was just beginning to venture out into the neighborhood yesterday. She told me that while the big apartment buildings, such as the one she lived in, seemed fine, many single-family homes had experienced blackouts or damage from falling debris. Jeeyeon, a student and dental office assistant who lived in Elmhurst, was unable to get to work in Flushing due to the subway stoppage, and her school was still closed. However, her mother had to go into work on Wednesday at KumKangSan restaurant on Northern Boulevard, and her father reported to work at a construction site, which they managed to do by car.

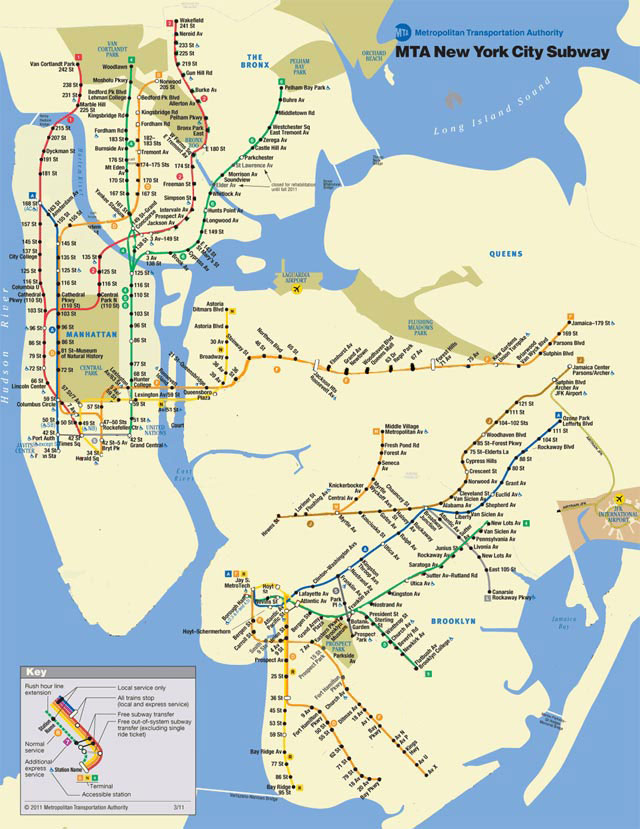

For Flushing residents who commute to Manhattan, the future is less clear. Long lines for the bus, the shortage of gasoline at gas stations, and the unwillingness of some cabs to drive into a city without working traffic signals make for uncertain and stressful commuting. Meanwhile, the MTA’s reduced service map, released yesterday, seems to erase the 7 line entirely.

This does not bode well for the days ahead for many Queens workers who depend on the line. Can the livery car service and other paratransit services in Queens handle this increased need? None of the Korean car services I called in Queens had the time to talk, although one hurriedly explained, “Yes, yes, of course we’re busy! We’re too busy to talk to you! Call in the morning!”

Scanning the Korean-language papers, it seems that many Korean small businesses in Flushing re-opened on October 30. For a few operations in Flushing, business was actually better than expected. For places with food delivery, like Corner Chicken, sales were booming—the owner guessed that food delivery and pickup was popular with the students and office workers who had been homebound.

For Queens-based social service agencies that I called, including Korean Community Services of New York, which runs a senior center in Corona and Flushing, and Korean American Family Service Center, which provides services and programs to domestic violence survivors and their families, the hurricane had not significantly interrupted their work. For Minkwon Center for Community Action, also based in Flushing, Halloween was a day to continue their door-knocking and phone-banking work to remind residents to vote. Priya Pandey, a 16-year old youth program member at Minkwon, went door-knocking as a zombie. She told me, “More people opened the door than usual because they were expecting trick-or-treaters, although some people had signs like ‘No candy because of Sandy.’ It was fun, getting candy and door-knocking at the same time. Most people did want to hear from us—they couldn’t believe it was already November. ”

As for Election Day conditions in Flushing, “none of the polling sites in Flushing and the area seem to be affected,” said Sabrina Fong of Minkwon. “But it’s been very difficult to coordinate with our ally organizations in Chinatown. They don’t have power, and with the subways down, it’s difficult to coordinate volunteers. We only have a few days left.”

I called the staff of Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, which is located in lower Manhattan’s Tribeca neighborhood. Bethany Li, a staff attorney, said the storm had significantly impeded the progress of the organization’s national election and voting campaign, which monitors voter discrimination and language access at polling sites throughout the country. With the presidential election only a few days away, the situation was urgent. Chi-Ser Tran, AALDEF’s voting rights organizer in the Democracy Program, explained that the lack of power in their office, public transit stoppage, the post office closure in the area, and other Sandy-related impacts meant that their effort to get vital election site monitoring materials to 14 states and Washington was delayed. “We have to send supply boxes to 100 poll sites before the election. This is our priority right now. Our office is on the 12th and 14th floor, and we are lugging these supplies up and down the stairs in the dark. Tomorrow, regardless of whether the subways are running or the power is back on, we are going to get these materials out.” With just a few days left, 800 volunteers had to be assigned to 100 polling sites, ready to poll voters, and Chi-Ser explained, if power wasn’t up and their exit polling software couldn’t work, they may end up entering the data on 10,000 exit poll surveys by hand.

In lower Manhattan, according to The Korea Times, Korean store owners in Soho, Little Italy, and other neighborhoods below 14th Street were stunned by the extent of flooding and had yet to resume business. Korean business owners shared that during Hurricane Irene, they had been able to pump out the floodwater and re-open quickly. But this time, with everything in general, from power to transit, stopped in the area, there was little they could do. For one Korean owner of a Little Italy-based restaurant, his entire first floor shop was entirely submerged by floodwaters.

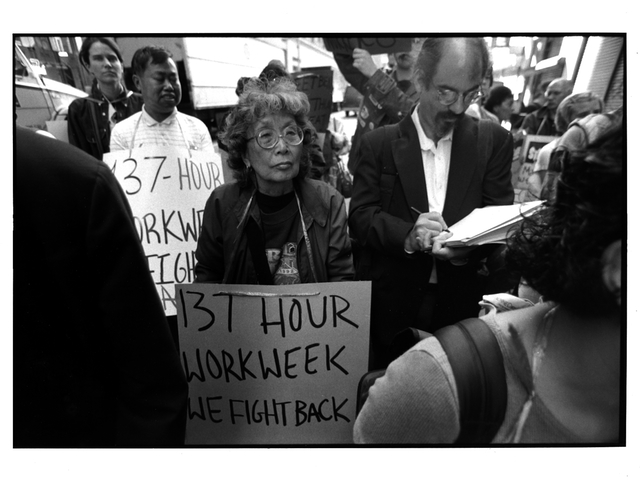

The stories of Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath in the mainstream and alternative press have so far included some acknowledgement of public sector workers, transit workers, and immigrant workers. “They keep the city running!” runs the triumphant script. This is true. In a sense, it is always true, but never more clear than when the rest of the city is still recuperating at home. Few talk, however, about how this may be linked to the lack of any other option—that the necessity to keep working is over-riding concerns about health or safety, for instance. Fewer still acknowledge that transit work, food delivery, and driving are some of the more dangerous and vulnerable occupations a person can hold, even without post-storm conditions.

Luna Ranjit, executive director at Adhikaar, a nonprofit organization for the Nepali-speaking community based in Woodside, Queens, told me, “Many of our members have live-in jobs as domestic workers and went in on Sunday, before the storm, and now, many are stuck in their workplaces without electricity.” In a sense, this was better than the situation of many other low-wage workers, who had not been able to work at all. But she updated me a few hours later with the news that one of the Adhikaar members, a domestic worker, had been called in to work from Queens by her employer because the apartment “needed cleaning.” She had waited hours for the bus, and cabs had refused to take her into Manhattan. For the city’s domestic workers, whose employee rights are laid out in a hard-won Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights, they are still among the city’s most precarious working sector, with sick leave, personal leave, and other paid leave policies left to the discretion of their employer. They join the thousands of other immigrant workers who are without such benefits, who may be wondering about how this storm will affect not only their paycheck for the week, but also their workplaces in the weeks ahead.

Lessons Learned

The gap between what the disaster mitigation field knows and the information that the general public receives is often astonishingly wide. Even though Hurricane Katrina seemed to surface the significance that race, gender, class, and other social factors play in disaster preparedness and response, there is still far too little attention paid to the more vulnerable sectors of the population and what the storm’s aftermath will mean for them.

A 2008 study of Asian and Latino communities in southern California by APALC and the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute found that many factors complicate how those with limited English proficiency, for example, receive information about how to prepare for disasters. Many city and regional agencies and national nonprofits, for example, do not provide disaster preparedness information in other languages, at least in real time. Immediate translation is necessary for transmitting life-saving information, as it is often intervention in the first 72 hours that can spell the difference in saving a life. Bilingual family and community members become critical in liaising with first responders and official relief personnel, but for some immigrant communities, past interactions with law enforcement make them reluctant or fearful to seek help. Those who are undocumented may fear seeking aid even more. For some immigrants, experiences of trauma, war, and catastrophe in their home countries may also trigger symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. More than ever, ethnic media often fulfills a critical role in translating official alerts and updates.

For New York immigrants, language assistance and translation services at public agencies remains a pressing, often unfulfilled need. A 2010 report, “Still Lost in Translation” found that many agencies still failed to provide language assistance to New Yorkers with limited English proficiency, with the Human Resources Administration failing to provide language assistance to 44 percent of those surveyed, and the NYPD failing to provide for 67 percent of those surveyed. Given that NYPD personnel are essential first-line responders in any community, this finding highlights how city agencies may be seriously unprepared to respond to immigrant communities in a disaster.

Moreover, in much disaster reporting, there is much evidence of a sensationalist impulse to feed the news cycle by framing exceptions to the rule as the general state of affairs. Disaster news coverage in the past has often gravitated towards instances of lawlessness and looting, for example, where minority populations are involved, even though the vast majority of disaster case studies show the opposite to be true—that people struck by catastrophe often band together, pooling resources and providing services where official channels have been interrupted or are inadequate. For immigrant communities, the gap is often filled by community-based organizations, religious institutions, ethnic media, and local volunteers.

In the weeks and months ahead, it will be essential to keep listening to the experiences of immigrant New Yorkers. Will communities be marginalized for not speaking and understanding English? Whose homes and businesses will be rebuilt, and when? Will strapped city agencies, with limited budgets, cut vital services or find ways to extend them? These questions and more should stay at the forefront of our understanding of how we can recover from a disaster like Hurricane Sandy.