“Our identities are made up of many, often conflicting parts, but are of us, nonetheless.”

January 5, 2022

We live in the dregs of Queens, New York, where airplanes fly so low that we are certain they will crush us,” begins Brown Girls, Daphne Palasi Andreades’ debut novel about second-generation women of color from immigrant families coming of age in Queens. Having immigrated from the Philippines to New York City as a teenager, I was struck by the profound sense of place in Andreades’ book from that first line. The novel is told from the collective “we” perspective of the “brown girls,” voicing experiences that also resonated with me—a love of literature unrequited by representation on the page; a perpetual sense of being in between cultures and never enough as an American or, in my case, a Filipina; walking the tightrope between our parents’ dreams for us and our own visions for ourselves.

Andreades considers Brown Girls an ode to women with a background like hers. Her parents had immigrated from the Philippines in the 1990s and planted roots in Queens, a majority middle- and working-class borough and the most ethnically diverse urban area in the world. Brown Girls began as a short story, which went on to win the 2019 Kenyon Review Short Fiction Contest, judged by Filipina American author Mia Alvar, and most recently an O. Henry Prize, selected by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Andreades found, however, that she couldn’t stop thinking about that world and those characters; so, she kept writing, and the story kept growing into what she reluctantly decided to call a novel. Over email last fall, we spoke about Brown Girls as well as reading, writing, teaching, and navigating life in a pandemic.

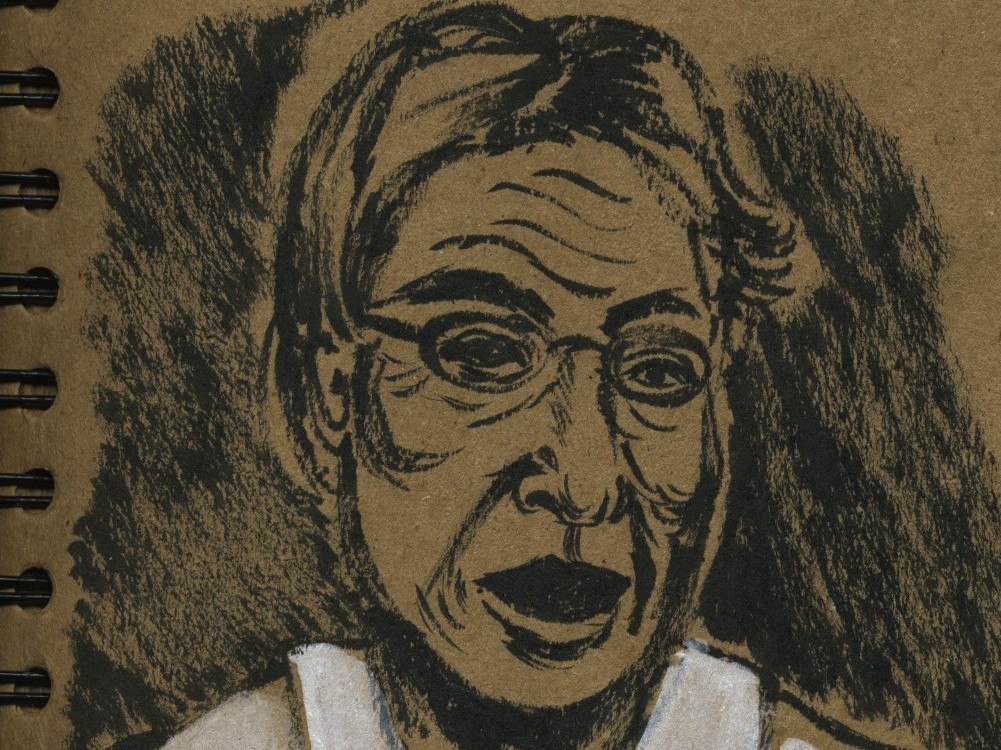

Vina Orden

You’ve cited the Toni Morrison quote, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it,” as motivational in writing your debut novel. Can you speak more about your experience as a reader? What was the first book you recall reading that gave you hope that there was a space for you as a reader and a writer?

Daphne Palasi Andreades

As a reader, one huge influence on me was the Queens Public Library. I’d go there after school or on the weekends. I was in middle school when I gravitated toward authors I came across in the Classics section: Orwell, Austen, the Brontë sisters, Fitzgerald. I remember really liking their sentences because I sensed each word was chosen with care in order to build these characters and worlds. Still, those Anglophone writers and their characters felt removed from the world I knew. In high school, I had a fantastic English teacher, Mr. H, who was intense and set high expectations. For one semester, we studied Black literature—works by W.E.B DuBois, Fredrick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.. Reading these authors was incredibly formative. Although I recognized my experiences as a Filipino American girl living in the twenty-first century were vastly different from these writers’ experiences, I identified with the racism, marginalization, and the effects of white supremacy that they illustrated in their work. These works helped me understand the solidarity and interconnectedness that could exist between people of color, even across different races and diasporas, which is central to my debut.

It wasn’t until later in high school and college that I began to seek out books by and about first and second-generation immigrants. Edwidge Danticat’s novel, The Dew Breaker, Jhumpa Lahiri’s short story collection, Unaccustomed Earth, and Julie Otsuka’s novel, The Buddha in the Attic—which greatly influenced the “we” voice in my book—were some of the first works by women of color authors that reflected communities I knew intimately. These authors also helped me envision a path for myself as a writer.

VO

There’s an urgency and currency in what’s covered in Brown Girls—for example, you allude to gentrification, the crisis at the U.S.-Mexico border, the war in Afghanistan, and the COVID-19 pandemic. What was it like writing in a time of so much upheaval? What made Brown Girls the book you had to write then?

DPA

I finished writing Brown Girls during the first wave of the pandemic in the United States. Writing was a practice that kept me sane during this difficult time. It was a space that held the entirety of my emotions—the despair and grief I had for the world during this time, my fear for family members throughout New York City who are healthcare workers. During these months, I questioned the purpose of art and my desire to write; both seemed, to me, unhelpful to others in a tangible way, not to mention financially precarious. But out of a combination of compulsion, stubbornness, needing structure, and a way to maintain my mental and spiritual health, I wrote—not for anyone else, but for myself. Brown Girls is an artifact of how I felt during this time, as well as everything that was going on in the world. And now, I still can’t wrap my mind around my debut being out in the world for readers!

VO

In writing a novel rooted in a very specific place, what do you hope readers come away with understanding about Queens, regardless of their familiarity with the borough and its people?

DPA

I hope readers come away with the sense of Queens being this extraordinarily vibrant place that’s bursting with life and filled with people who are striving. I felt compelled to write this story set in Queens because, although it is the most ethnically and linguistically diverse place in the whole world, it’s one that is underrepresented in art and literature. I wanted to expand the narratives that exist and allow readers—if I may say so—the privilege of entering this place and these characters’ lives, in all their beauty and complexity. I view a place like Queens as emblematic of both the ideals and failures of America: Queens has this beautiful mix of people, cultures, languages, and beliefs, all co-existing; yet many of these people are invisible within American society or perceived as outsiders when, in fact, they belong just as much as anyone else. My debut confronts this pain, challenges it, and asks questions about how to make sense of these different parts of one’s identity as a person of color and immigrant living in the United States today.

VO

Did you always envision writing the novel from a collective “we” perspective? What was your intention in blending the girls’ experiences of intergenerational family conflicts, racism and classism, love and relationships, and their journeys of self-discovery?

DPA

After writing the first sentence, I knew the novel couldn’t be told from any other point-of-view except the “we.” The “we” is a chorus of women’s voices, in which characters within this chorus are free to come and go as they please—sometimes they have whole paragraphs dedicated to them, sometimes they show up in one scene and reappear in others, or sometimes an entire life is expressed in a single sentence, and you never hear from them again. There’s a fluidity to this choral point-of-view, an ability to expand and contract at will, that I found really fresh, a challenge I wanted to pursue. Julie Otsuka’s 2011 novel, The Buddha in the Attic, executes what I’m describing so deftly. The “we” was a method of capturing the solidarity and shared experiences of women of color of different diasporas from this particular neighborhood—of being immigrant daughters, of feeling a deep obligation to their families yet wanting to pursue their own paths, of grappling with cultural and gender expectations, of being hyper-visible and invisible in America, and trying to make sense of the seemingly conflicting aspects of their identities.

VO

Another way that Brown Girls sets itself apart from a conventional novel is its hybrid form—you can read it in part as a prose poem or even a lyric essay. What does poetry allow you to do that a conventional novel doesn’t?

DPA

My background in creative writing actually began with poetry. My poetry classes impressed upon me deeply and influenced how I approach my fiction, especially my debut. Poetry taught me about concision and precision, as well as paying attention to rhythm and musicality. Before fiction, I also spent several years painting and drawing, though I always kept a journal. Poetry and visual art taught me about the importance of having striking images and evoking an atmosphere, which I brought into my fiction.

In college, one of my poetry professors introduced me to Claudia Rankine and Maggie Nelson. These writers challenged and expanded the notion of what I thought writing—not limited to one genre—could do. Their work wove visual art, quotes from interviews they conducted, history, philosophy, and much more. Their approach, which I saw as representative of an artistic freedom and voraciousness, stayed with me.

Brown Girls uses vignettes to structure the story; it incorporates lists, song lyrics, snippets written in Spanish, Tagalog, Hindi, Arabic, and more. I interviewed friends as preliminary research to the book; I used their responses as a springboard into imagining scenes, conflicts, an atmosphere. Parts of the novel were drawn from my life and others were invented. I love that the word “novel,” as an adjective, means “new.” I think the novel as a literary form should embrace innovation, which is often born from an artist being unafraid to combine disparate elements. However, I would say that the book’s formal choices are merely a reflection, and an extension, of the characters’ hybrid identities.

VO

As a Filipina, I too identify as a brown girl, and something that resonated with me was this idea of contradictory expectations, which set us up for failure, and being in a constant state of “in-betweenness” rather than “belonging.” For instance, we’re chided for being too American but aren’t supported when we want to learn our own language, history, and culture. What were you trying to convey by choosing to present these vignettes in the book?

DPA

These contradictions are mind-boggling, aren’t they? Of being American but not American “enough”; of being, simultaneously, for instance, Filipino but not Filipino “enough.” But this myth—the damaging idea of “purity,” which is the polar opposite of hybridity—was one I wanted to expose and critique in my work. Our identities are made up of many, often conflicting parts, but are of us, nonetheless. In Brown Girls, the characters ask: Am I the colonized or the colonizer? Am I American, or can I claim ties to this other country my parents left behind? Do I stay in my hometown, or do I leave—and if I leave, does this signal a betrayal? Yet, phrasing these questions as binaries are limiting, incomplete, and in the end, false. Our identities are myriad. It’s a myth that we have to choose.

VO

A number of scenes take place in the classroom, showing the dynamics between students and teachers whose authority they can’t help but question or defy. In an early chapter, “Musical Chairs,” teachers routinely mistake one brown girl for another, calling them the wrong name. Then, there’s the chapter “Western Epistemology,” where the narrator reflects on characters in Shakespeare and Greek classics who look nothing like them. What were you hoping to illustrate through these classroom scenes?

DPA

Through these classroom scenes, I wanted to examine how educational and academic institutions act as modes of assimilation. Schools have the power to pass on the beliefs and values of a culture—often of those who have historically been in power. I wanted to convey the invisibility that the characters experience, whether by teachers who don’t know their names, the Eurocentric syllabi, or at universities where the characters’ peers and teachers are predominantly white and wealthy, which contribute to girls feeling alienated. Of the different manifestations of structural racism that Brown Girls examines, how it appears in our education system is one of them.

However, I am thankful that my personal experiences aren’t identical to that of my characters. I attended New York City public schools from kindergarten through undergrad, and while they have problems of their own—overcrowded classrooms, teachers who work their asses off but don’t get compensated enough—I had many amazing teachers who encouraged me to think critically, and whose syllabi were quite diverse and comprehensive.

VO

On the topic of education, as a graduate of Columbia University’s MFA Fiction program and as someone who has taught creative writing, what would you say to other women writers of color who are considering an MFA program but doubt whether they or their writing belong in such programs? Is there a piece of advice you wish you’d gotten sooner in your writing career?

DPA

My advice to other women writers of color is to write what interests you, and to remember that your experiences, whether or not you bring them into your art, are incredibly valuable. I’d recommend seeking out art by and about historically marginalized communities and finding community—mentors and other artists—who identify as BIPOC. Seek allies, as well. It was my community who helped me look beyond my fears and focus on my art. I’d tell my younger self to be unafraid of claiming space for herself, and to remember that it is necessary for her to do so. I’d tell my younger self that, though the arts can feel very white and wealthy, money and whiteness do not define an artist—inventiveness, curiosity, drive, and persistence do. I’d tell my younger self to trust her vision alone, and to let this guide her.