In Queens to “clash,” Japanese dancehall kings Mighty Crown talk old-school Brooklyn and dub plates

December 13, 2013

[Editor’s Note: This is Open City’s first installment of “Lyrics To Go,” a collaboration between writer Rishi Nath and multimedia journalist Nabil Rahman. The series features conversations with contemporary musicians whose life and work intersects both Asian-American communities and New York City neighborhoods. For this article, we’ve provided a handy field guide for those new to sound clash culture. Check it out below this article.]

A competition was underway. It was 10pm in Queens, and in a grey building with no signage, just down from Sutphin Boulevard, a crowd of two thousand people waited quietly as the former reggae champions, Mighty Crown, prepared to take the stage.

Over a decade ago, in 1999, this musical group from Japan shocked dancehall fans by winning Brooklyn’s World Clash—the most popular deejay competition in the reggae world. Since then, every sound system from Jamaica to London had been gunning for them. And so, on this night, at Club Amazura, in Jamaica, Queens, thousands paid $60 to enter. And, hundreds who came after midnight shelled out more.

Near the stage, men in tilted hats and graphic tees gathered around buckets of beer, while women sporting crisp hairstyles slipped through the crowd, looking for a good spot to watch. The scent of marijuana wafted throughout the space.

Mighty Crown didn’t disappoint.

Sami T pressed a button on his laptop, conjuring royalty. The familiar, sandy voice of Jr. Gong, son of the reggae prophet Bob Marley, boomed out from the crescent of 30-foot speakers.

“Them never stand a chance/ They diss Mighty Crown and dem will dead inna the dance!”

Entering the fourth round in a traditional Samurai outfit, Masta Simon, the preeminent voice of Mighty Crown, was comedic:

“In Jamaican term, you might say: Mi swag tun up!” The crowd signaled its approval with raised arms and a chorus of nasal air horns. Someone in the back raised a Japanese flag.

Japan caught the reggae bug around the same time as the rest of the world. “Bob Marley, reggae’s main international ambassador, performed in Japan in 1979, and it is Marley to whom more Japanese reggae fans trace their first exposure to the music,” writes anthropologist Marvin Sterling in his 2010 book, Babylon East: Performing Dancehall, Roots Reggae and Rastafari in Japan.

However the popularity of Jamaican music in Japan over the last decade came from the more electronic “dancehall” style. And, the link between Japan and the larger dancehall community was, unexpectedly, a nucleus of deejays in Brooklyn.

In the early nineties, Masta Simon, and Sami-T, brothers from Yokohama, moved to New York. They connected with another Japanese expatriate, Coji, and called themselves Mighty Crown. Together they apprenticed with other music collectives, or sound systems, and developed a fluency with both the reggae canon and Jamaican patois.

They also toiled, working construction and other jobs to earn money for personalized versions of reggae songs, called dub plates. They wanted to clash—that is, to compete with other sound systems for crowd approval, a tradition in Jamaica that stretches back decades. The two brothers were dedicated to mastering the form and proving themselves in competition.

In 1999, Chin, a Queens music promoter, half of the duo Irish & Chin, was searching for an act, perhaps new contenders to spice up an upcoming clash. “I went to Brooklyn looking for another Japanese sound system,” he said. “They were no longer available for touring. However, my friend said there was a sound that was pretty good, named Mighty Crown. So I booked them.”

Chin didn’t anticipate what happened next; no one at the Warehouse in East Flatbush Brooklyn did. Mighty Crown took top honors, even with deadly sound systems like Killamanjaro and Tony Matterhorn on the bill.

Instantly, they became global dancehall celebrities, winning clashes in Boston, London and Jamaica. Together with dancer Junko Kudo, the first non-Jamaican to win the Dancehall Queen competition in Jamaica in 2002, they helped spread dancehall culture throughout Japan. “When I asked fans and people in the industry about dancehall’s popularity, the very consistent reply was that it had to do with Mighty Crown’s victory in 1999 as well as Kudo’s,” writes Sterling.

…the link between Japan and the larger dancehall community was to be, unexpectedly, a nucleus of deejays in Brooklyn.

Just days before World Clash 2013, Lyrics To Go caught up with Sami-T, Masta Simon, and Ninja Crown (Mighty Crown’s American representative). In the spare offices of Irish & Chin, just above a record store in Hollis, Queens, the three musicians reflected on their journey, returning to the clash stage at Amazura, and the early years in Brooklyn.

************************************************************************************

Take us back to the early days of Mighty Crown in Japan.

Sami-T: I was 16, 17 at the time. We were teenagers just getting into music. I started listening to hip-hop like Public Enemy, stuff like that. They had a party going on—which was a reggae party. We were teenagers we couldn’t even get into clubs. This person named Junior Dee who was a veteran reggae deejay used to be at the gate. When we seen him he used to be like “Alright, you guys can get in.”

Masta Simon: There weren’t much clubs. We come from a city called Yokohama. That’s where we used to hang out. That’s where Banana Size were playing. They had man like Junior Dee and Papa U-Gee. I got a lot of influence from them.

You guys went to English-language school, and then the States. Did your proficiency in both standard English and Jamaican patois help your success?

Sami-T: Simon went to California; I was the one who came to New York, it was 92. I really started hanging in the corners of Brooklyn and I was hanging in places like Flatbush, Church Avenue, just trying to learn the language because patois was a little bit different—a whole lot different—from English, y’know. I didn’t even know the word bumboclaat, I thought that was a good word. [Laughs.]

Masta Simon: Well English is one of the major factors why we are ahead of a lot of the other rest of the sounds. Without English and patois, language is like a barrier. You got to know how to speak, you got to know how to listen.

On the other hand, Ninja Crown, you’ve been to Japan many times now. Have you felt the need to pick up Japanese?

Ninja Crown: Well honestly, when it comes to Japanese language, I may know one or two words. But when you deal with music, I don’t have to know the language. They go off your energy and vibe. Reggae music is universal. If anything, I use Sami or Simon to translate.

The first experience in Japan was crazy. I didn’t know what to say, what to do. But Japanese people love the music—authentic foundation dancehall music. They love that.

Now I’ve been to Japan countless times. It’s like my second home. I think I’m more popular than Sami and Simon still. [Laughs.]

So what happened during those first few years that you moved to Brooklyn? Where did you live?

Sami-T: I started living in downtown Brooklyn, I believe. I think it was 541 State Street. And then that’s where I kinda met Coji. The experience at that time was—I could say… incredible. Now. At the time it was a disaster, in a way. Because it was straight black people neighborhood, right? Caribbean neighborhood and then you don’t even see one Japanese on the road. And I was like one of the few set of Japanese on the road. And they would be like “Yo Chin, Yo Jap. Come outta street! You don’t belong here!” kinda vibe.

And all these youth on the street bad me up. It was rough, really rough out there. But I was trying to get in the language. Well, Jah guide me through.

I’m still here. I coulda dead ‘pon the street. Cause ‘nuff shot a rinse dem time deh. Like a lot of gunshots busting up when I’m in the street. Bap!Bap!Bap! “Where shot a fire from?” It was real street shit.

Do you remember the first dancehall party you went to in Brooklyn?

Sami-T: It was the Biltmore with Stone Love and Addies. It was Supercat. It was incredible. I had two Heineken beer… right? I couldn’t go to my second beer! That was the kinda experience that me did have. It was my first experience with the sound system. Big speakers.

Addies used to have two eighteen-inch speakers with like a double scoop. I was just chilling and in front of the speakers… drinking one Heineken was coming like five just because of the speakers. I wasn’t even used to the sound system… just standing in front of the sound system your tee shirt start move. Boomp-boomp, boomp-boomp, with the bass. I was like bloodclaat… wah dis?

And I even remember myself fainting in the dance. Like “I feel sick now”… me go inna in the bathroom and lay down, ‘pon the corner, sweating and everything.“Jesus, why am I here, why did I come here?”

Then this youth, tell me like “You alright? You alright youth, Mr. Chin, you okay?” And it was a man from EarthRuler. Everything kinda connect now, Jah know? That was the time I first met EarthRuler.

So after I come out from my lickle [little] faint. And I was like giving thanks, like“thanks for trying to help me out.” They were like“What do you do? You play ‘pon a sound system?” And I was like “yeah, I’m trying to build my sound. My sound named Mighty Crown.”

So they invited me to their crib, and they were like “Can you spin?”And me start show them what me can do at that time… apprentice kinda vibe, right?. EarthRuler was one of the hottest sound in Brooklyn. They were like,“Tell you the truth, you nah mek it. You’re not on that level.”I was like“I want to play on the parties and stuff.”They were like, “I invited you to see just to see where you skills were at. But you nah mek it.”

But…look at where I am right now!! [Smiles]

When did you decide to become a sound system that clashes?

Masta Simon: I still remember one of the clashes in Brooklyn, at Biltmore. Addies and Bass Odyssey, for the first time. Squingy was there—actually Squingy was alone spinning. That kind of like changed my whole career, my way of thinking. I was like, “Yo I want to clash with these guys.” When I saw Squingy, I was like yo… I should deal with this the right way.

I said “Yo, this is really interesting.” Cause you never see this culture nowhere else. Not in Japan, nowhere. The whole sound system culture was so different. Especially the clash thing was so different. You had sound like Addies, ‘Jaro, Bass Odyssey. I was like “Yo, I gotta clash these guys, yo, we gotta beat them one day.” That was my goal back in the days, early nineties.

Once was your first experience with Amazura in Queens? Did it feel different coming from Brooklyn?

Ninja Crown: My first experience playing Amazura was with a sound called King Agony, when King Agony went to World Clash.

Masta Simon: Agony went to World Clash? [Laughs]

Ninja Crown: Yeah. One thing about New York fans, they will cheer for you one minute and in a split second they will forget about you. I was nervous behind the turntables. Back then we weren’t playing CDs and laptops, we were playing dub plates. So you had to make sure the needle was right on the dub plates, precise.

Has Amazura become the new Biltmore?

Ninja Crown: Biltmore? Yes.

Masta Simon: It’s a different vibe. It’s a different space.

Ninja Crown: But it is the prestige stage for clashing.

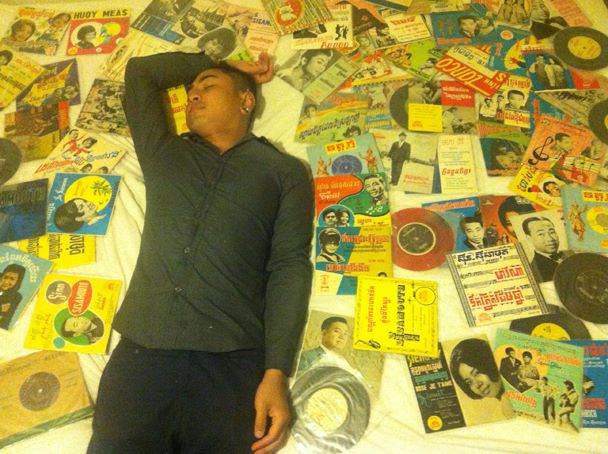

Once you decided to clash, you had to start getting dub plates. When and what was the first dub plate you cut?

Sami-T: The first dub that I ever go voice was in ‘92, and that was in Brooklyn. I got my information from one of the shops in Manhattan. There was a guy named Reverand Badoo, he’s one of the Brooklyn artists. They used to have a Brooklyn restaurant. I wanted a Nicodemus dub. And they took me to a studio in East New York. Old Veteran, Bonanza, Sound Killer. To name a few.

Is there a story about getting a dub plate that really sticks out in your memory?

Sami-T: Wyclef is another story I can give to you. The first time I met Wyclef was when I clashed with Rodigan in Connecticut. That was after we win World Clash.

Wyclef just step on the stage and hand him the dub; Rodigan had the link already. He just had a big song with Carlos Santana.“Ma-ria, Mar-ia…” It was a wrap.

Wyclef came to me after the clash. He probably felt bad. I was just sitting there and he said “I’m a big fan.” And I was like “Yo man, move your rasclot…you just tek side!”

Any other tune I play, it just didn’t work….Dennis Brown, all the classics. It didn’t work. I was like: “Damn!”

Wyclef came to me after the clash. He probably felt bad. I was just sitting there and he said “I’m a big fan.” And I was like “Yo man, move your rasclot… you just tek side!” But he invite me to his studio, which was Record Factory in Manhattan.

Eventually I told him: “Yo, I’m having a rematch with Rodigan coming up in Amazura. Now is my time. What’s up?

He hooked me up with a dub plate. Then it was my turn to give it back to Rodigan. It was a counteraction!

Masta Simon: We played it first before Rodigan. He was surprised we had it; that was his secret weapon.

Do the strong political messages in some reggae music about Babylon and the Western system resonate with Japanese fans?

Masta Simon: Hmm. That’s a delicate question. A lot of people just come to have fun. If you got a hundred people, you have a hundred minds. But you have a few Japanese artists who talk about the system: “Don’t be like the slavery of America!” cause of the World War II, and stuff like that.

We do a lot of charity work, like after the big earthquake. We talk about a lot of political things too, through music. Cause rebel music is part of reggae music.

We always put one or two song about the system. Cause the system is really fucked up, from our view too.… like Nanjaman and Ackee & Saltfish who say never forget Japanese culture, that’s the root.

Sami said he was often taken for Chinese amongst Jamaicans in Brooklyn. There is a Chinese community in Jamaica. How do they interact with the Japanese visitors who come for the reggae?

Masta Simon: Nothing tense going on. We got like Chinese background too. We’re mixed in a way; but we were raised in Japan. So we got different-different culture in our background too. That’s something that a lot of people don’t know.

Sami-T: Well, I think its like in Jamaica is that everyone is Chin. Period. They didn’t really know what Japanese or Korean or Chinese is. Like I might not know who is Jamaican or Trinidadian or who comes from Barbados.

I don’t really see Chinese people who live in Jamaica who go and party the way the Japanese do. They don’t fall in love with the music the way the Japanese do. Just like us—we just flew in there and see and go to the dances and lime with the Jamaica crowd. That’s a difference.

Masta Simon: But we don’t really mingle with the Chinese people who live in Jamaica. We might go to a Chinese restaurant, we talk, but we don’t flex with them…

Sami-T: ..and they don’t flex with us neither. We’ll be like“Wha gwan?”

And they’ll be like….“What do you want?”[Laughter]

But now a whole generation is coming up“mixed”. Half-Japanese, half-Jamaican; half-Chinese, half-Jamaican. It’s going to be interesting.

Masta Simon: It is.

**********************************************************************************************

Essential Field Guide to the Sound Clash

Addies: Refers to King Addies, a legendary Brooklyn sound system

Amazura: A nightclub in Jamaica, Queens which often hosts World Clash.

Banana Size: A foundation Japanese sound system.

Bass Odyssey: A historic Jamaican sound system.

Biltmore: A legendary Jamaican nightclub in Brooklyn, since closed.

bumboclaat: A curse word in Jamaican patois.

counteraction: A dub plate that responds to an existing dub plate.

dub plate: A customized version of a hit song including the name of the sound system.

Dennis Brown: A conscious reggae singer known as the “Prince of Reggae.” He died in 1999.

EarthRuler: A popular New York sound system from the nineties.

foundation: A artist, sound system, or record considered to be instrumental in the development of reggae music culture.

Killamanjaro: A legendary Jamaican sound system where Supercat and others got their start.

Nicodemus: A dancehall reggae artist from the early nineties associated with Supercat. He died in 1996.

patois: A dialect of English spoken in Jamaica.

rasclot: A curse word in Jamaican patois.

Rodigan: A British radio personality who became one of the greatest clash selectors of all time.

selector: A person responsible for choosing which song to play on a sound system.

sound system: 1. A collection of reggae selectors. 2. The actual apparatus used to broadcast sound including speaker boxes, wiring, and mixing equipment.

sound clash: A competition among sound systems using dub plates, counteractions and talk to incite the strongest crowd response.

Supercat: An iconic dancehall reggae artist from the early nineties known with infusing reggae into hip-hop.

Squingy: An selector on Jamaica’s popular Bass Odyssey sound system. He died in 2009.

Tony Matterhorn: A former King Addies selector who later became an artist and scored a hit with“Dutty Wine.”

World Clash: A popular sound clash promoted by Queens duo Irish & Chin.