The poet on her ghosts and inspirations.

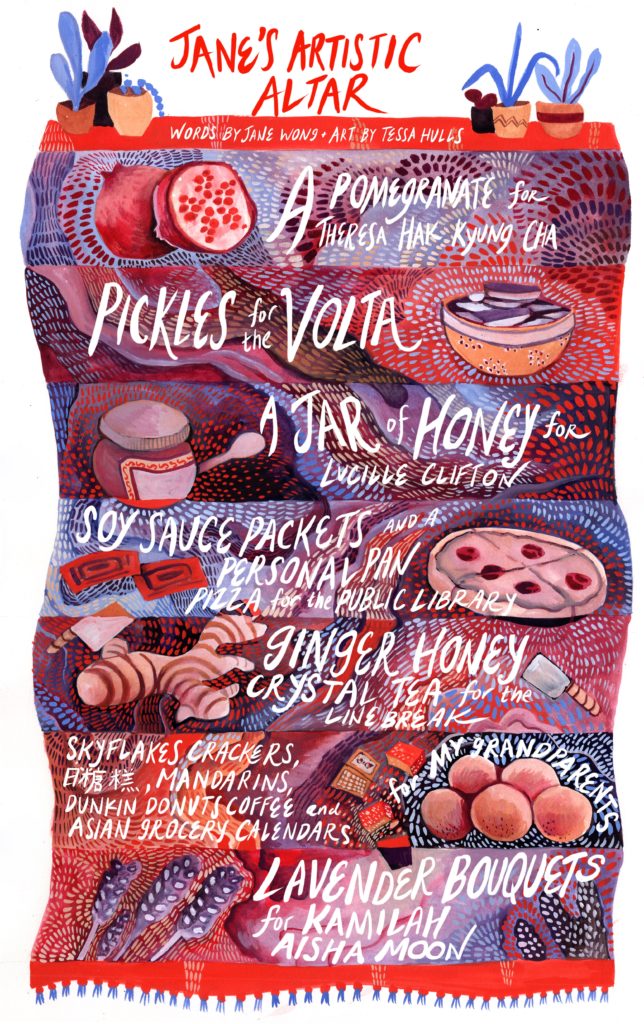

A pomegranate for Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. I was eating a pomegranate the other day. My mom called me and told me she was also eating a pomegranate. On FaceTime, we flipped our phones to show each other the fruit, cracked open and craggy. The seeds both bitter and sweet, little ruby fisheyes. In 2016, I visited the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Archive, where Cha’s collection resides. I came across her artist book from 1975, Pomegranate Offering. The book is tied together by soft cloth threads. From within, a line: “by RECALLING devotion.” I recall Dictee as the first book I read that made me feel haunted. And bewildered. This book shaped me over many years as a writer, encircling the past as the present and the future. When I visited the archive, I was the age Cha was when she died. May these healing seeds sing along her tongue.

Pickles for the volta. I love fermentation. The sour funk, the stinging sharpness of acid seeping through. How a cucumber can turn into a pickle—absolute magic. I love pickles swimming in sesame oil and vinegar, topped with chili flakes. I love eating them after something fatty like pork dumplings. The volta—broadly defined as a turn in a poem—is my favorite. I love how you never know when the poem will turn, how it will pivot somewhere you didn’t expect. I think of Gwendolyn Brooks and her poem “when you have forgotten Sunday: the love story”: “And chocolate chip cookies— / I say, when you have forgotten that, / When you have forgotten my little presentiment / That the war would be over before they got to you.” Oof! Every time! How that startling word “presentiment” leads us into that heartbreaking turn. I love the shudder of the volta—whether it be thematic, sonic, tonal, formal, etc. I always begin a poem not knowing where it will go. I roll down multiple hills, valleys, flood-fevered rivers. And there might be multiple voltas, pivoting me in directions only my ghosts, my grief, my love might know.

A jar of honey for Lucille Clifton. Clifton was one of the first poets I fell in love with. The warmth of her words, her music, her knowing sent me diving into the depths of this poetry-thing. From the beginning of her poem “new bones”: “we will leave / these rainy days, / break out through / another mouth / into sun and honey time.” Poetry feels like that honey time, that “worlds [that] buzz over us like bees.” A space where we can tell our stories, rewrite our histories, find safety in ancestral survival. It’s another world, another “mouth” that is always open, always cavernous and full of possibility. When I was born, I didn’t blink or cry. My mother told the nurse: “She knows too much.” I did and I didn’t. Clifton’s words open up my second book, How to Not Be Afraid of Everything: “i will keep the door unlocked / until something human comes.” I am so grateful for her words, her vision. I set jar after jar of wildflower honey for Clifton, glittering spoon at the ready.

Soy sauce packets and a personal pan pizza for the public library. I grew up in a Chinese American take-out restaurant on the Jersey Shore. I spent all my time there, cleaning poop veins out of shrimp and cutting strips of wonton wrappers to fry. The public library was close to our strip mall, pretty much across the street. Sometimes my mom would leave me there for hours upon hours by myself, where I’d read in a corner. The librarians were my best friends. I ended up working at that same public library for all four years of high school. I worked as a page, reshelving books in the children’s section. A baby of the eighties and nineties, I racked up so many personal pan pizzas from Pizza Hut’s BOOK IT! I could cover the entire Jersey Shore in crusty cheese. I became a writer because of food, because I was voracious for all the senses.

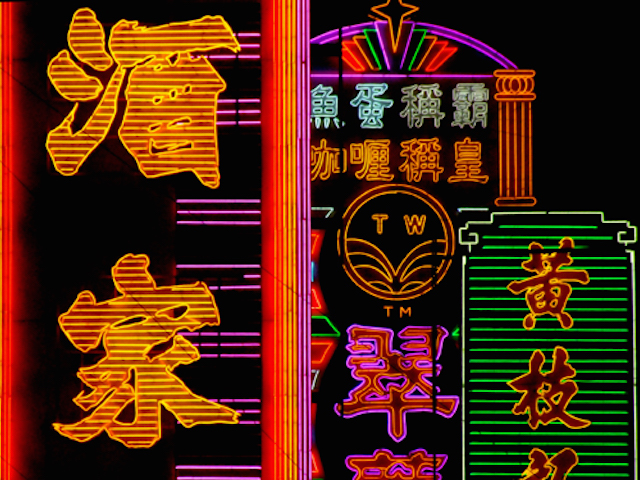

Ginger honey crystal tea for the line break. I began as a fiction writer and spent my Fulbright year in Hong Kong back in 2007 writing flash fiction and/or prose poems. They were little nuggets of something, blocks of tofu, dense blankets. I didn’t think much about shape then, and I definitely didn’t think about the line break. Around that time, I applied to MFA programs in fiction, and applied to both fiction and poetry at the University of Iowa on a whim—with prose poems. While I got into fiction programs, I was like oh, what the fuck. Let’s write poems. And so I came to Iowa without knowing anything about line breaks or craft (shout-out to my good friend Nicholas Gulig, who taught me so much then). Or anything really about poetry except that I was drawn to it, that maybe poetry articulated something I’d always known. When I’m feeling foggy, I drink ginger honey crystal tea. After pouring hot water, I stir it up so that it froths on top. I watch it settle and think of my mother chopping ginger with her cleaver. I think of line breaks when I think about her cleaver. Sometimes the thinnest slivers. Sometimes hacking at chicken bones and gristle. I think about the smoothness of her round cutting board, about space breaks too.

Skyflakes crackers, 白糖糕 Bak Tong Gou, mandarins, Dunkin’ Donuts coffee, Asian grocery calendars for my grandparents. How can I do anything without honoring my ghosts? I come from storytellers who hold entire tables in suspense, rice flying out of their mouths in laughter. I also come from humming silences imparted by terror to them. What to talk about, what not to talk about, the ways one communicates love. I set these daily gifts for my Gung Gung, Ng Ng, and Yeh Yeh. The free calendars from the Asian grocery store especially so they know what I’m up to these days. My poems are also gifts, though I should probably gild them in Ferrero Rocher wrappers just to be extra clear.

Lavender bouquets for Kamilah Aisha Moon. In the summer of 2017, I spent a month writing at Hedgebrook on Whidbey Island. I can’t believe how lucky I was to meet Aisha there—a stunning poet, hilarious storyteller, and generous soul. The day Aisha arrived, she, Jasmine An, and I spent the night cuddled up in the farmhouse’s library drinking whiskey, laughing our asses off. Loved talking to Aisha about poetry, desire, grief, music, dreams, tarot cards, healing, teaching. She sent us all a Frida Kahlo quote via email: “You deserve a lover who listens when you sing, who supports you when you feel shame and respects your freedom; who flies with you and isn’t afraid to fall. You deserve a lover who takes away the lies and brings you hope, coffee, and poetry.” I vowed to find love like that and I vowed to love myself this way too. At Hedgebrook, we wrote through everything that poured out of us. I wrote the beginnings of what would be my memoir and put the bones together for my second book. Aisha and I fed llamas and crushed blooming lavender in our palms. We kept in touch, sending sweet messages from time to time, and she wrote the tenderest words for How to Not Be Afraid of Everything. When she joined the ancestors, I couldn’t believe it. From her poem “To a Camellia Blossom”: “I kneeled / and cradled you, petals sighing / into grateful palms.” I am setting down lavender bouquets from Whidbey and camellia blooms and Prince songs for dear Aisha.