An illustrated dispatch.

November 27, 2012

For many, the steps to recovery post-Sandy will be long and complicated. Is rent due when no heat, power, or hot water is available? Does flood insurance cover hurricane damage? How do I recover lost wages? For those who have lost loved ones, the loss is even more staggering.

The immediate language of disaster relief is a little more elemental, and many are still engaged in it. Food? Medicine? Shelter? Diapers? Flashlights? Are you okay?

Volunteering in Chinatown before the power came back on, and unable to speak Chinese except for “I don’t speak Chinese,” “I am Korean,” and “I love you,” this basic language of needs made up my script.

On the first Friday after Sandy struck, I biked over the Williamsburg Bridge with friends, our bags laden with sandwich ingredients. We stopped at the office of CAAAV: Organizing Asian Communities, located at 46 Hester in Chinatown. CAAAV’s darkened space was filled with the smell of peanut butter. By the light of a single bulb powered by a rumbling generator, an assembly line of sandwich-making volunteers worked quickly.

The organization was part of a patchwork of aid spearheaded by community organizations across Chinatown and the Lower East Side, operating in the absence of FEMA, the Red Cross, or other traditional first responders. Even the local police precinct had a sign on their door pointing people to 46 Hester. How could it be that organizations with miniscule operating budgets like CAAAV were the main hubs of emergency relief? But it also made sense—they could hardly shutter their doors and flee to a friend’s house uptown. They knew what the community needed.

By day 3 of CAAAV’s relief efforts, volunteers were fulfilling specific requests that came from nearby residents and canvassing broad areas of the neighborhood to talk to people who had been unable to leave their homes.

We got our assignments. My team of four was sent to canvass East Broadway going left on Rutgers. A resident let us into our first building after giving us a scrutinizing look. Our only identification, after all, was pieces of blue tape stuck to our clothing with the word “Volunteer” scrawled in capital letters.

We entered the first building and devised an impromptu strategy: Start on the top floors, where people might have the most difficulty getting down to retrieve necessities, and make our way down from there. What follows are fleeting encounters that have stayed with me as the weeks have passed.

I had heard about the darkness from those who had fled Chinatown, but I didn’t fully understand until we entered the first building. Pushing forward into lightless corridors felt like we were moving within a bad dream, as if light was the same as air, and lacking that, the dark was an airless abyss. Our flashlights helped a little, but they also made the walls bounce, the stairs shimmer. They didn’t take away the initial feeling that each turn, each unlit hallway filled with looming objects, was uncertain and precarious.

So we climbed the stairs clumsily. We would catch our breath, and then we would begin knocking.

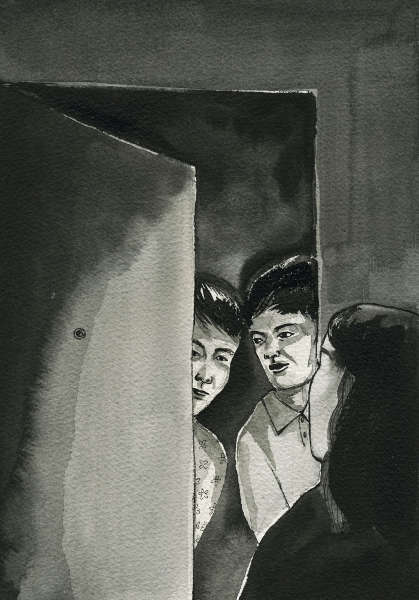

We stood before the first closed door. Our knocking sounded thunderous. It reminded me of our volunteer briefing: we were to knock one door at a time, with only one person speaking at a time. The buildings were old and the hallways narrow, and everything echoed. People were scared to open their doors. No one knew us. Be considerate.

We listened for sounds behind doors, like rookie detectives. Was anyone coming? Was it hard for the resident to walk to the door? “Hello?” we would ask, for the third or fourth time. Our Cantonese-speaking friend would also try one more time. Sometimes, I felt foolish.

Yet we kept knocking. In the narrow tenements, there were four to six apartments to a floor. Sometimes we just got one eye staring at us, a small voice asking, “What do you want?” Many told us, “No one has come by,” and took some donated food and a flier. In one building, most people had fled. Some hallways smelled like food rotting. Other times, a quiet door would inexplicably fill me with dread.

At one door, it took a long time before anyone came, but we could hear them moving. Young women in pajamas peered out carefully. They seemed sleepy. Even though it was daytime, their apartment was dark. They declined the food, but they wanted fliers.

We quickly realized that numerous buildings had been rendered inaccessible by the lack of power, silencing the buzzers. So we also approached passerby in the streets. People looked curiously, eagerly, at the informational fliers we passed out in Chinese or Spanish. “When will the power come back on?” was the refrain.

When we ran low on supplies and turned back to replenish at CAAAV, we noticed two women hurriedly unloading FEMA blankets in front of a senior housing complex on Henry Street. “Can you help us unload blankets?” the women asked us. We said we had a little food and water. Perhaps we could combine forces.

A Chinese-American woman paced outside. Her mother was inside. She had driven to the city from upstate New York. She couldn’t reach her mother. She had no electricity or heat either.

We all waited for the super together. When he came, we piled the blankets into the lobby. The super said he would deliver them. But the building was many stories and we wondered how he would manage by himself. So we began the trek, carrying five blankets each and our meager supplies. Twelve stories is a long way in the dark. Here, the stairs did not lean and creak, as in the tenement buildings. But they felt more unforgiving, harder on our feet.

On the eighth floor, an elderly woman slowly came to the door. She accepted a blanket and nodded as we held out the food, and we began to place cans in her arms and then on the floor near her. She stood there smiling tentatively, repeating, “Thank you! God bless you!” in English. As we turned to leave, she stayed in the doorway. She began speaking in Chinese to our Cantonese-speaking friend.

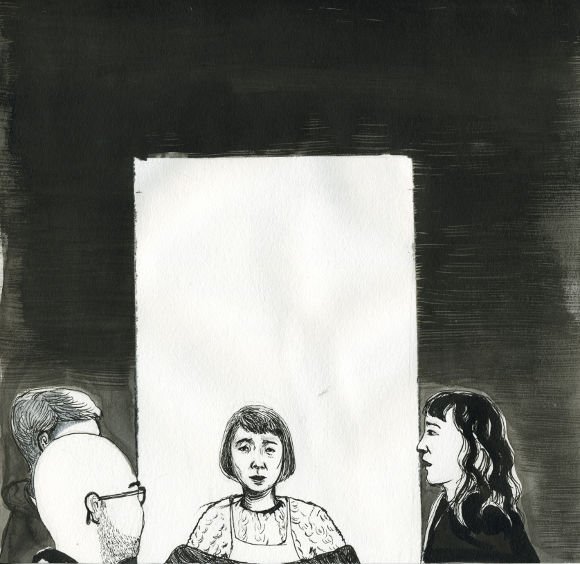

Our friend told us, “I can’t understand her fully.” The resident kept speaking. Before long, both were weeping, as the resident continued to speak, her eyes bright with tears.

Our friend, wiping her face, tried to translate. “She is asking, ‘Where is my son?’ “She has been so afraid.” “Her son is in Hong Kong.” “She hasn’t heard from anyone.”

We thought we should stay for a little while. We offered to bring in the food instead of leaving it in the doorway. We stood in her narrow kitchen, placing the goods down as she continued speaking. Our friend couldn’t understand everything, but continued to nod, listening. The woman counted off on her fingers, and said in English, “My daughters, my son.” It seemed she had many children, but no one had been able to come by or contact her.

She showed us her room. The living room was piled with luggage and wrapped packages. They each had her name and apartment number taped onto them. It wasn’t clear if she expected to be rescued from the building or had just moved in. Was someone supposed to come? Why had no one come? I held her brittle hand while we listened to her talk. We learned her name was Mrs. Wong. Holding her frail shoulder, I questioned the logic of senior housing—filling tall buildings with elderly residents seemed cruel in cases of disaster or power blackout. When we left, we noted to ourselves the woman’s name and apartment number to tell others to return.

In another apartment, we were knocked back by the smell of gas burners when the door opened. A smiling elderly woman greeted us at the door. Suspecting that they might be using their gas burners to heat the apartment, we asked to come in. In the living room, we met a chair-bound elderly man who was delighted by the hand-powered flashlight we gave him. They both smiled, unable to speak much English, nodding at the blankets we offered. We also discovered there was someone else in the house who hadn’t come to the door—a young man who had stayed seated and silent and didn’t greet us, unlike the other home attendants we had met. We asked him to turn off the gas. He nodded. We left, still feeling uneasy, again noting down the apartment number.

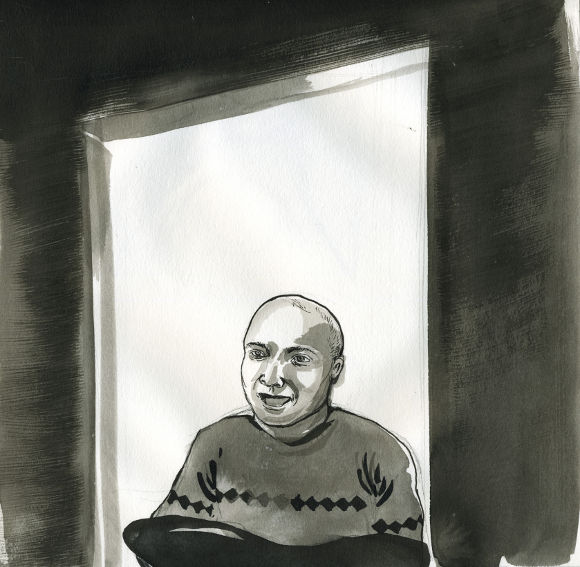

On another floor, a middle-aged man answered the door. As we began talking, he gestured to his eyes. I began to suspect that he couldn’t see us. Someone put a blanket into his hands. He frowned for a minute, but then recognition shone out from his face. “Blankets!” he said triumphantly.

“Yes, blankets!” we echoed eagerly.

“Thank you!” he said, beaming. “Thank you!”

He accepted some water bottles, and then turned to close the door. I wondered why he was alone, why some residents had their home health aides with them, and others were left to fend for themselves.

We made our way back to CAAAV, quieted by our memories of the elderly residents at the Henry Street housing complex.

We passed other smiling teams of volunteers, some who appeared to have no Chinese speakers in their group, and I wondered how they would manage. We could see a line of people moving steadily with boxes into the tall public housing buildings near the East River.

After re-stocking our bags at CAAAV, we received a second assignment: canvassing Norfolk Street. The street seemed to hold both new condos and old tenements. “Isn’t this whole area gentrified?” we wondered aloud. One curved starchitect-designed building especially gave us pause. But we encountered many elderly Chinese- and Spanish-speaking tenants in the street, and we realized that despite the swanky bars and restaurants at the street level, that this was not the case.

In one building on Norfolk, a young resident accepted some food and told us, “I think I know two folks who could use your help.” She guided us to the fourth floor. We stood before their doors. These doors stood out, with the layers of paint on the wood paneling transforming them into laquered ghosts of their former selves. Elderly Spanish-speaking tenants greeted us, and some took food and fliers.

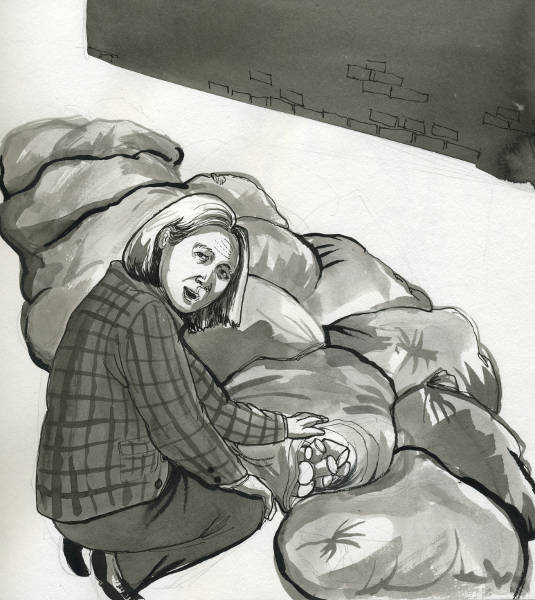

In front of the last building we canvassed on Norfolk, we met a Chinese-American woman looking in bags of discarded food. She was rescuing apples and bananas, and salvaging packaged food from a bag full of yogurt containers. She told us that she lived across the street, and that her husband was sick. We gave her what food we had. But it wasn’t enough. She continued to search the bags, and when we left the building, six stories of door-knocking later, she was still there.

And then on our way back to CAAAV, at 4:52 p.m., pausing at a restaurant serving only tater tots and fries on the corner of Rivington and Stanton, the power came back. A roar went up the block and all around us, the din of an entire neighborhood celebrating. Our friend, who lived in Chinatown and had volunteered with us, slumped with relief. Finally.

It struck me, retracing our route and noting all the homes I had entered, that the storm had temporarily shifted the norms around private space, property, and personal boundaries. In a landscape of uncertainty, small community organizations had activated a gift economy among strangers, and neighbors had come together. What would remain of this good will as difficult decisions around housing and resources were made? What impressions would stay with the hundreds of volunteers who had canvassed Chinatown? Had new commitments been made, or would the demands of daily life pull people back into their individualized routines?

Crossing the Williamsburg bridge back into Chinatown, we saw that the power restoration to the area had led to an unexpected downside: a fire was burning on the top floors of a still-dark public housing tower. The billowing smoke seemed to signal that the transition back to life before the storm would perhaps be more complicated than we knew.

In the days following power restoration to the Chinatown area, CAAAV has re-routed volunteers and donations to affected areas like the Rockaways and Coney Island, while working with Urban Justice Center and volunteers to provide free legal assistance in Chinese to local residents about FEMA, lost wage complaints, and other assistance programs on the weekends.