To fix myself, it seems, is to become a ghost of myself.

December 19, 2019

The summer before I enter high school I am going away to camp. It is 2011, and my first time—camp is a small and perfunctory childhood milestone that I have somehow missed on past cycles of the season. To go now, at fourteen, feels like growing small again.

Here is what I know about the camp going in: it is in St. Paul, Minnesota; it is for South Korean adoptees also from Minnesota, although midwesterners from out-of-state are also welcome given they meet all other criteria. That’s rather specific for a summer camp, says my grandmother over the phone, don’t you think?

Given historical context, the requirements make sense. After the Korean War, the United States made a major push to encourage transracial adoption as a way of providing homes to children who were, in one way or another, displaced by the war. Children were born only to be orphaned or shunned due to their mixed-race heritage, considered unwanted reminders of wartime. South Korea stabilized, slowly, but this did not stop the trend of international adoption. Adoptees are no longer plucked from war, but instead are drawn from the pool of those born to single women, or to families who are too poor to care for them.

An enclave of adoptees began to grow in Minnesota. The state by happenstance had been home to a perfect and improbable storm of adoption-friendly policies and a homogenous Scandinavian population, who were blissfully unjaded by the interracial conflicts that plague the rest of the country. Minnesota welcomed this new minority with open arms until it became home to the largest concentration of adopted Koreans in the United States. Understanding this history makes the appearance of a camp seem like an almost natural occurrence, like a canyon formed by a river, alleviating the loneliness of a single rock by carving it in two.

I am recommended this camp by my best friend Anna’s family, who insist, quite assuredly, that Anna had returned home the previous year with apotheosized feelings of community and heritage that of course could not be provided by their White Catholic Family, and implicitly, our White Agnostic one. Anna and I were born three months apart on the dot in South Korea in 1996, and were adopted, independently, to families in a farming town in Illinois that boasts a population of just over 8,000. Our parents, also the same age, met in the agency waiting room. I imagine my mother has a prescient sense that to not send me to Minnesota would be diverging our lives in a risky and experimental sort of way, a clinical trial for a congenital cultural defect for which Anna would be treated and I shuttered away, as if in a control group. This guilt remains unknown to me, but it must be powerful, seeing as my mother soon packs the three of us (Anna, Myself, and our adoptee friend Lonnie) into a car to be taken 400 miles north. At the outer limits of St. Paul, every building looks as though it is possessed by a young couple trying to grow themselves, the house, the inevitable business, into one. The windows light up, beacons of structure and settlement, until the trees swallow them whole.

I find the camp neither revelatory nor especially disappointing. It is exactly how I imagine every other sleepaway camp for children, except that we are heavily encouraged to cry. There is an expectation of trauma and internal displacement on the campers that I do not believe I share. At dinner, the counselors take turns getting up in front of us and relaying their Adoption Story. We are taught that all of us, too, have Adoption Stories of our own (save the handful that only meet the Minnesotan and Korean eligibility requirements) and that regardless of how we feel toward the circumstances of our birth in general, we are welcomed and valid. During these times, I squinch my face, wondering if the absence of feeling is also “valid” or if it means that I am, like one percent of all children, a little sociopath.

The dining hall is beautiful, air conditioned. It smells strongly of Lemon Pledge. The smell of Lemon Pledge floats through the rafters above like the ghost of whatever wedding reception or corporate gala was here before us. It’s easy to tell we are in the type of camp that considers the outdoors an afterthought. The indoor space is cool and clean and spacious, in stark relief to what the kids are supposedly sent far away to enjoy. This is also how you know that a camp is for outcasts of some kind—for them, the beauty of the woods lies not in the landscape but rather in its lack of those who make you feel, in their company, somehow more alone. I have asthma, and the citrus fumes labor my breathing. I try to feel the way I see Anna is feeling, like I am experiencing comfort for perhaps the first time.

Several of the camp’s counselors are fully Korean by citizenship. They are not adoptees, and the camp’s decision to employ them is subject to interpretation—my theory is that we are more likely to accept their lived experiences as authentic, rather than our own watered down versions of Korean identity. Although we are all South Korean by blood, we do not look the same race. The majority of us are tan with stockier builds, drowning in oversized neon t-shirts that commemorate middle school soccer teams and church-sponsored 5ks. The four Korean counselors, particularly the three women, look like how we imagine K-pop stars. Never before have I seen a person so fully embody the words lithe or wraithlike or impeccable. Their very presence stirs something within us, some deep-seeded suspicion that the tall, blonde, tennis-like women we were taught to mould ourselves into with sheer will of envy were merely all-American diversions, designed to make us hate ourselves in our futility to emulate them. It is our first time seeing people who embody an entirely different standard of beauty in the flesh, one that we secretly hoped was, if not more achievable, at least less laughable to covet.

I do not feel coddled when we speak with them. It feels as though we are being let in on the world’s secrets, which exist behind an imaginary paywall that can only be bypassed with two or more decades of life experience. My favorite of the three is Yi-Soo, who has a tiny forehead and wears her hair in a bun. Yi-Soo squats in front of me on an ottoman and does my makeup. The cleaner in the air mixed with the makeup powder irritates my sinuses and makes my face feel like a warm water balloon left on the hose valve, slowly swelling from within. When the girls are alone, we have questions that the other counselors could never answer for us, such as, Am I pretty to Korean people?

All girls are either Cute or Beautiful, Yi-Soo tells me as though presenting findings from years of well-kept research. Esther is Beautiful, Anna is Beautiful, she continues. She pulls back from me, makeup brush in hand, examining her work from a distance. Her eyebrows, straight as limousines, near a head-on collision. You are…Cute.

Yi-Soo goes in a circle around the room categorizing us into either one category or the other. She speaks perfunctorily and without pause. Her metrics are not stated, although I can guess. Long straight hair, slim features, good skin. The word Cute alone is not derogatory, although when it is used as a euphemism, it carries an underlying weight. Like the words Mixed and Half, and how if another camper were to say you looked Mixed, what they really meant was that they thought you were attractive. The boys, sidling up next to Anna in the dining hall in their best athletic shorts, would always slyly ask her if she was Half, because they were just wondering, you know she could be, yes, it was something about the structure of her face, and then their eyes would slide down, away from the features that had sparked the conversation in the first place. Cute can not mean cute when it is positioned as the opposite of beautiful. I know this because Yi-Soo says that I should grow my hair long and consider using a skin lightener to help attract boys. When she leaves me alone with the hand-mirror, I can see that Yi-Soo’s makeup is far too light for either her or my face. To fix myself, it seems, is to become a ghost of myself. My eyes begin to water. The bright light is coming in through the windows, and my sinuses are irritated again.

In the car going home, Anna, Lonnie, and I huddle in the backseat and cling to one another like wet linen in a pile. Perhaps I did not love camp, but it has spoiled me. I am no longer used to standing out in a crowd. Lonnie stares back out the window in silent rage. He, like Anna, had found home there, and as we drive away, and his rented community pulls back and so too is swallowed by the forest, the thread tethering him pulls and unravels, until he is alone again. I move my face out of the path of the light that has followed me from the cabin and is now barreling in flippantly through the window’s half-inch of glass, taunting me, making me shine back with sweat. I recede further back until the vertebrae of my spine are plugged perfectly into the seams of the car’s upholstery. I do not willingly go out in the sun bare for the next five years.

Two years later I am much paler. I stay inside whenever possible and when I look in the mirror I see only scorched earth. Hormones have ravaged my skin, and my latent desire to stimulate my hands has blossomed into a full-blown skin picking disorder. I try and fail to rub myself away. Parts of my face are permanently dark, as though I have shaved them, and I know that I will live the rest of my life with a face like the moon. I beg my mother for Accutane, which she adamantly refuses. She has heard the horror stories, and believes that the drug will make me want to kill myself. I remember Yi-Soo’s advice of skin lightening. I figure that she must have done something herself, to look as she did, like white paint in water. I spend hours combing the internet looking for ways to lighten skin quickly, and I do not accept no for an answer. I hold Yahoo Answers to the same degree of plausibility as I do the Mayo Clinic. I pay no attention to sources that tell me what I want is impossible and the result of pure, unalterable luck. I assume they are lying to me, to prevent me from doing something drastic.

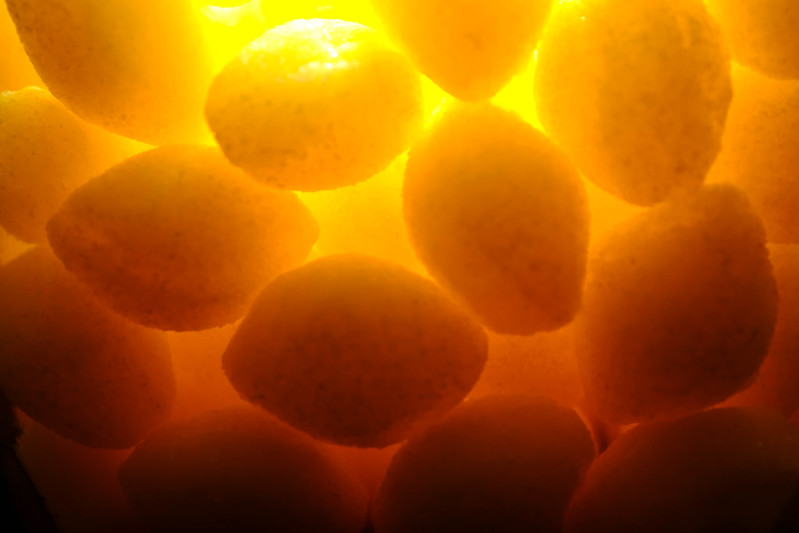

I find a series of articles online touting the effects of lemon juice as a panacea of sorts, capable of bleaching the skin naturally while also eliminating acne and scar tissue. I believe the claim wholeheartedly. Of course acid is the only substance strong enough for what I want. I picture it melting me down to base matter and building me up again like I am a simple and moldable thing, perhaps a product of clay, or snow. The author’s photo in this article is of a blonde woman, smiling at something I cannot see. I can tell that she is on a beach somewhere.

I ask my mother to buy a bulk bag of lemons at the supermarket, telling her that I plan to suck on them for a snack. The request does not phase her, as I often ask for foods that burn my mouth numb. I take the bag up to my room with a chef’s knife, feeling a rush normally reserved in children for the arrival of a new plaything. I lay the lemons out in front of me and begin to cut one in half on the floor. I stop when I hear the dull thunk of blade on hardwood. I am afraid I will scratch the floor and somehow reveal myself. I squeeze the half-lemon onto a Kleenex and the sensation is evocative of popping a large zit with both hands, deeply satisfying and primal. The juice seeps into the raw skin beneath my nails and I can feel a little reminder of my heart’s pulse in my fingertips. I suck my fingers. My mouth waters.

I dab the damp tissue on the problem areas of my face, this is to say, all over. I think of my acne as an expression of my body’s anger. I have pushed and compressed all of my bile deeply inside and now in response it is pushing its way through my pores in protest, the same way a Play Doh doll grows its colorful wax hair. My skin feels angry and I cannot tell if this means it is purging or dying. I will begin to do this a bit each day, feeling triumphant until the day I finally begin to crack open and bleed. Sitting on the floor of my room I look down at the arrangement I have made and wonder, cynically, if it were not more fitting to call myself a lemon than a banana, yellow on the outside and bitter on the inside. I, too, am dripping with spit. I wonder if the fruit would care why I am doing this, if I could explain myself. Here is what I would want to say:

Hello I am sixteen years old and my face is made of baby fat and covered in boils like what God did to Job. My body is getting lighter by the minute because I blew out my birthday candles and wished for vitiligo and it drives me crazy that most of my blood has never seen the light of day. Like you, my brain is also a lemon, one that was sold to me on the day I was born and made it fourteen years off the lot before breaking down, smoking on the side of the road. I smell like the indoors.

In the dead of night, almost one year later, bursting at the seams with what I will someday recognize as intense mania, I pour a half inch of straight bleach and apply it with a washcloth to my skin. I am careful to leave an inch radius around my eyes and hold my breath as much as possible to avoid inhaling the toxic fumes. I hold the cloth to my face seven minutes at a time to the second, listening to the hum of the radiator in my basement, feeling horribly ill and yet completely in control. This, like all of my modes of self-destruction, will only dissolve years later with help, with time, and the undoing of threads that have been winding for years. In the moment—my breathing labored with the smell of bleach, like Lemon Pledge—I feel overwhelmingly clean.

I will demolish the way I think as I grow older, and rebuild, slowly. It is years before I admit that there is something wrong, and even longer before I recognize that there is nothing wrong with me. I allow the sun to touch my face without guilt, knowing it will likely be a long time before I have ownership of myself again.

Years later, the bleach has left minimal damage to my skin, which I think of as nothing short of miraculous. I have finally earned back visitation rights with my own body. I am beginning to enjoy the taste of lemon again.