“I logged onto the Internet and searched for others like me. I never found them, but I invited them over to my hotel room anyway.”

February 7, 2013

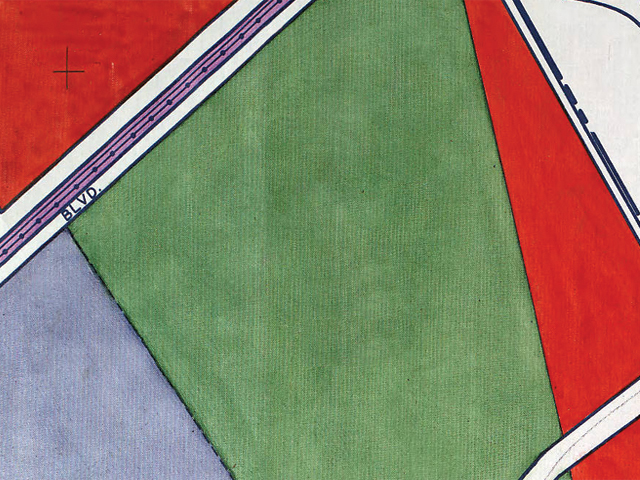

They built the city and named it Centum.

For weeks there were no stoplights. Instead, there were only blinking yellow lights, and I played chicken with the oncoming traffic at every crosswalk on my way to work at a hagwon on the 39th floor of an office building. It should have been simple to get from one building to another—turn right, walk straight. And yet, I would get spun around on the big, wide sidewalks. I would take the wrong turn, cross the wrong street. Everything was so angular, so tall, and so metal, that I could imagine—beam for beam, pane for pane—this city’s birth inside of a plexiglass dome.

Let me be clear: Centum City is not a real city. It is a part of Busan, a port city on the southeastern tip of the peninsula, where the South Korean and U.S. armies fled during the war. Half of the peninsula pushed into the city, building makeshift houses out of plywood and cardboard to block out the wind and rain. The older architecture of the city still reflects the need for function over form. Houses stack on top of one another, steadily ascending mountain slopes in scattered assemblages to accommodate the stream of refugees that did not seem to stop.

Centum exists in the future perfect: it will all have been worth it. The developers promise jobs and money in figures so large they lose their meaning. Eight trillion won. Two hundred thousand jobs. They razed an old airport to create a new city, a highly controlled, urban planning project meant to entice tourists and venture capitalists alike. There is, now, to the north, a Shinsaegae, which has the distinction of being the world’s largest department store, with a Spaland, an ice skating rink, and a multiplex. To the east there is BEXCO, a cavernous convention center that plays host to car shows, ophthalmology conferences, and art exhibitions. The developers of this place named themselves and their project Centum, Latin for “hundred”—the city of 100 percent.

I stood at the first intersection where there are four coffee shops at each corner, locked in an eternal stand-off: a Starbucks, a Caffe Bene, an Angel-in-us, and a Tom ‘n Toms. It is a triumph of capitalism to suggest that there is a choice in the matter. Of course, I adjusted, and I chose. I chose the Caffe Bene because it had a balcony. I would sip green tea in clear glass mugs alongside women with thin calves and pale skin. I joined a gym and exercised at 4 p.m., before the after-work rush began. I wandered under the fluorescent lights at the Fresh Market in the basement of the Shinsaegae, filling my basket with overpriced nectarines and pale chicken breast wrapped in cellophane. I eventually learned I could do all of these things without getting lost or forgetting what to do.

I lived in a hotel room on the ninth floor. It had a washer, a small kitchen, a television, and an Ethernet cable. The furniture was cheap and smelled of antiseptic, and the carpet was a lurid beige. There was never enough sunlight, no matter how wide I spread the jacquard blackout curtains. I cooked my meals on the electric flattop and watched variety shows on the flat screen. I streamed porn on my laptop and jerked off. Sometimes I would wander naked to the window, where I could see the shiny black carapace of the unfinished building across the street, the hotel’s neon lights dancing across its surface.

I was reading Open City, and I found myself, like Teju Cole’s flaneur, a man adrift in his own thoughts. I tried to leave Centum. I took the subway and walked around neighborhoods where the ground was littered with the familiar detritus of flyers for kiss rooms and whiskey sets. I ate porky stews with noodles from restaurants that boasted fifty-year old recipes. I sat on the sand, staring at the bridge on Gwangalli Beach. I tried to write, but couldn’t follow a thought for long enough to see where it would lead. I had a home, many homes—in Seoul, in New York, in Florida—and I had left them and could not remember why.

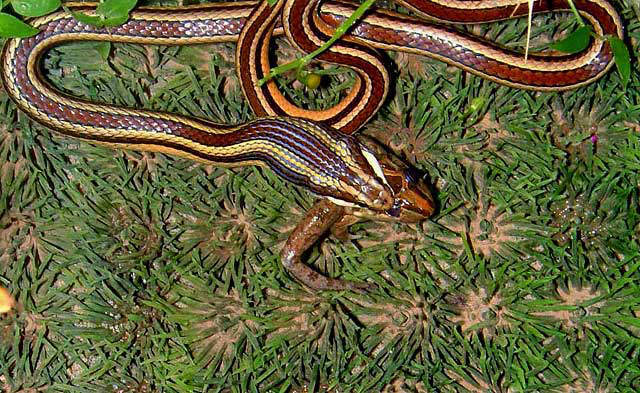

I logged onto the Internet and searched for others like me. I never found them, but I invited them over to my hotel room anyway. I texted one of them to come over around midnight as I was leaving a birthday party for someone I didn’t know. It was pouring rain that night, and I remember his shoes squished as he took them off at the edge of the carpet. Do you want a beer? I’m sorry you came all this way in the rain. He shuddered. (Was that a no?) He asked if he could shower and I said he could. He was thin and slight and when he took his clothes off, I could see the bones in his back as clearly as the fine teeth of a fish’s spine. As I fucked him I looked down at his face to see his eyes searching for the corner of the ceiling. There we were, fucking away our loneliness.

Centum would wind down around seven p.m., once the office workers had gone to the beach for round two. I would venture out to the garishly lit convenience store on the next block, but take the long way, tracing the criss-crossing grid like a gerbil that has mastered its maze. The sidewalks were unnaturally clean, and even though it was summer, the wind would hiss through the streets. I would stand with plastic bags filled with bottles of tea and chocolates shaped like mushrooms, staring at the empty facades advertising plastic surgeons and dentists. This is what struck some deep anxiety inside of me: the knowledge that it is entirely possible to lose yourself when you are alone.

One of my last weekends in Busan, I was wandering the streets of Seomyeon, flanked by bars and restaurants full of things that I wanted to drink and eat, and I felt a vague foolishness realizing that I would leave without having gotten to know the city at all. I wanted to keep walking, go down to the gay neighborhood, get a drink, maybe two, maybe meet someone, maybe have sex. Instead I took the subway back to Centum City and stared at the feet of a woman wearing a pair of green sandals with two red beads dangling like cherries.