If I can learn its grammar and alphabet / hold its vocabulary in my mouth / then perhaps I can know something of history—my history.

May 15, 2018

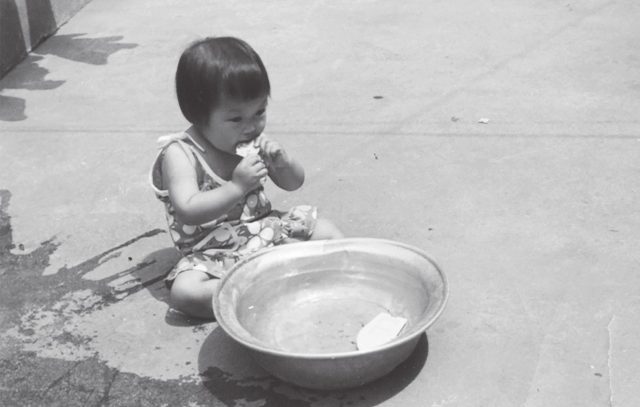

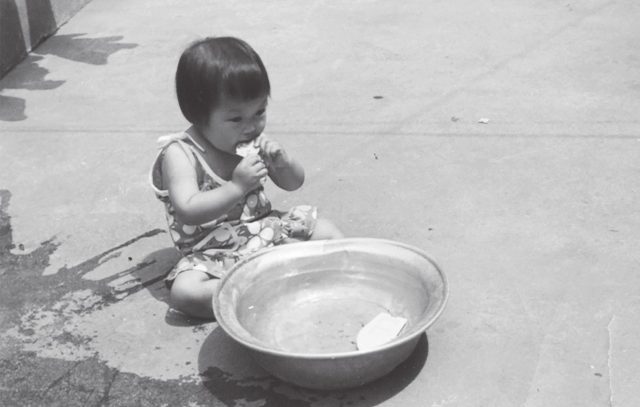

In Litany for the Long Moment, her new collection of linked lyric essays, artist and poet Mary-Kim Arnold pulls together the work of writers like Susan Sontag and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, with her adoption papers, official questionnaires, childhood photographs, and Korean language learning exercises. Writing into the rupture of family, identity, and diaspora, Arnold’s assemblages compose a new, lyric self out of everything that has been lost.

Day 5: Korean language IV

Our instructor tells us that Korean sentences are ordered as either:

subject + verb, or

subject + object + verb.

There is no verb inflection for tense or number. There are no articles.

Relative pronouns are not used and there is no gender agreement with

pronouns. Passives are not commonly used. Many verbs are not subject

to being passivized.

He makes up, on the spot, a silly anecdote to illustrate the difference

between Korean and English syntax.

Your friend calls you on the phone, he says, and the connection is not

good. You want to tell your friend to bring you an apple. In English, you

would say:

“I want an apple.”

But the phone cuts out before you finish the sentence. So all your friend

hears is “I want,” and she would never know what it was you wanted.

In Korean, you would say:

“I apple want.”

Your friend would hear the important words—you and apple. Your friend

would know something about you and about the apple. Or, in Korean,

you could just say “apple,” and assume that your friend knows it’s about

you and could probably conclude that you want an apple. And then she

would bring it to you.

We all laugh. But I want more.

I want to know: Is the fact that a relationship exists between the subject and

the object of the sentence more important than the nature of that relation-

ship? Or more important than the action that transpires between them?

Q12: What motivated you to do a family search and when did you start?

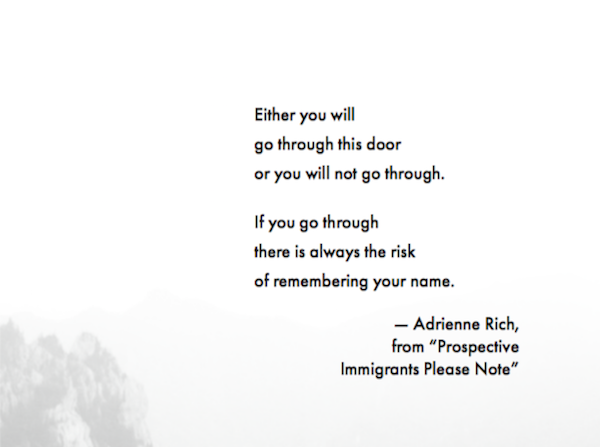

I want to believe I carry Korea in me, in my blood and bones.

That my body remembers something of my mother, my father, my first home.

That Korean-ness lies dormant, waiting.

That maybe language is one way back.

If I can learn its grammar and alphabet

hold its vocabulary in my mouth

then perhaps I can know something of history—my history.

If I can speak it, then maybe I can know its topography—

the rugged mountains that run down the peninsula like a broken spine,

wild river that bisects its cities.

If I can name its flora and fauna, its national flower,

if I can sing its national anthem,

if I can learn the right words for mother, for longing, for love,

then maybe I can recover some lost thing.

I fear this is asking too much of syntax.

Q7: What is your opinion of Korea?

There is a belief among Koreans who embrace Won Buddhism that our

destinies are determined by forces we cannot understand. That decisions

have been made about our lives long before we are born. Pre-written.

Before I was born, it was written.

Before I was born, there was the war.

Before I was born, there was one mother and one father.

And I was born, as it was written.

And the rupture, too, was written.

I am writing into the rupture, the absence left there.

Day 12: Visit to Mt. Sorak (One of Korea’s Most Beautiful Mountains)

In the last days of the trip, they take us to Mount Sorak. We stay in a

resort hotel, play casino games.

It is as if we are the only people there. We wander the carpeted hallways

with our paper cups filled with tokens. We drink cheap soju and laugh

loudly. Spread ourselves across the pink couches in the lounge.

There is a late-night disco in the hotel and so we dance.

There is a private room for karaoke, and we sing American songs until we

can no longer stand.

In those small hours, we talk about what we remember. What we think

we can. Fleeting images.

A bowl of persimmons.

Dogs barking in a fenced yard.

A man in a dark suit, standing at a gate.

Or maybe we have dreamed them.

The way a dream can be a memory.

The way a memory can be a wish.

This excerpt is reprinted from Litany for the Long Moment by Mary-Kim Arnold. Copyright © 2018 by Mary-Kim Arnold. Used with permission of the publisher, Essay Press. All rights reserved.