Community organizing can be lonely work when you’re battling ghosts from a violent past

December 12, 2014

Shahid Khan has two faces.

In Little Pakistan, he goes about his day-to-day life blending in with his south central Brooklyn neighbors, stopping to shake hands or nod an as-salaam-alaikum to those he passes by.

The area, officially called Midwood, got its nickname because of the ethnic makeup of its residents. Shahid says the neighborhood has become a coveted location for Pakistani immigrants and that he and many others choose to live there despite paying rents higher than elsewhere in the borough.

Halal eateries line the main roads. Newspaper boxes with Urdu publications dot every few blocks. Bodegas sell Pakistani spices. The many mosques are crowded on Friday afternoons. The grocer across the street from Shahid’s apartment often lets his family have bread, sugar, oil, and other staples on credit when he’s struggling.

“This is my community. I know their attitudes and behavior,” he says. “The culture is the same as at home. You know this is your place.”

But the elements that create this comfort are the same ones that make Shahid feel he needs to hide the part of himself that’s driven toward social change and still healing from the trauma he suffered due to political violence in Pakistan.

“Here, in the grocery store, restaurants, laundry shop, I’m only able to talk my daily life… So I always keep to myself that identity – that I was a human rights activist.”

For Shahid, Little Pakistan means kinship. And yet it also means isolation. He doesn’t openly share his ambitions or his adversities – other than the financial woes common in the community – with the sweet shop owner who gives him work behind the counter from time to time or the man at the daycare who lent him $200 to make ends meet while he is out of a job.

“Being a social worker and a community worker, I have a very different mindset,” he explains. “I think this is a problem: people who are coming from their homeland country, they have the same life as in Pakistan, and they have the same kind of extremism as in Pakistan. Now they are here. So maybe there is something dangerous for me. That’s why I never discuss with them.”

His solemn, earnest demeanor as he speaks of his challenges seems at odds with the everyday face he shows most people. He answers the phone with an animated “Hallooooo,” and adds smileys at the end of his texts. He tears up easily and then stops himself, reminding me that in Little Pakistan, the men are supposed to be men.

Shahid, 44, came to the US on asylum from Lahore, where he was born and raised. He worked since the mid-1980’s on issues such as human rights, social development, youth empowerment, and a democratic agenda. But as religious extremism and the War on Terror made his activism increasingly dangerous, he concluded that a life far away was better for him and his family.

“I have selected a very difficult life,” he explains. “But at least here I have some sort of, you know, freedom. In Pakistan the political situation is totally different. Here I have solidarity in terms of freedom, in terms of lawfulness. I have some sort of security. There are institutions. That’s why I am still working and surviving.”

This life-altering move was set off by events in 2009, when Muslim extremists stuck a metal rod in his thigh as he protested the Gojra riots, in which eight Christians were burned alive outside of Faisalabad. The incident left him incapacitated for two months. After Shahid migrated, his wife, Nazia, and daughter Maryam were abducted and attacked as well, fueling his fears that they are all continued targets of persecution. His first months in the US were shaped by recurring nightmares and visions of these experiences.

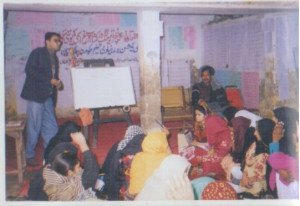

But these psychological scars are only part of Shahid’s ongoing internal battle. His desire to continue working for progressive change within his community also faces resistance from others. He has tried to establish trainings and workshops for new Pakistani immigrants to Midwood to challenge attitudes on gender, class hierarchies, religious differences, and more. His views make him an outcast of sorts, and at those moments neither his soft demeanor nor his genial exchanges along Coney Island Avenue ease the conflict.

“This is actually… this is my passion,” Shahid says. “I cannot live without this work. Because I am doing this work since my childhood, now this work becomes part of my life. It’s not something I can live without, these programs. I cannot live. And my community here, I see they really need my work; they need me. So I can’t do taxi driver. I can’t become construction worker. I can’t do gas station. That’s why I believe that I need to work in my own field, my passions.”

“I cannot live without this work. Because I am doing this work since my childhood, now this work becomes part of my life.”

Shahid attributes his devotion to change society in part to the death of his father due to stomach cancer when Shahid was in eighth grade. As we drink green tea and talk at Bahar Masala, a halal Chinese restaurant, he traces a diagram of sorts with his hands on the table. He outlines the housing complex he lived in growing up among an extended family and describes how his mother was forced to fight for the assets she was left in her husband’s passing. Shahid’s father’s brothers made her compensate them for the value of the home and required that, moving forward, only she and her kids live there – other family members would have to leave. Because women did not have the same rights to property as men, she had to comply.

What his mother was able to resist, however, were offers from the larger family to support her children financially; she knew that nothing came for free, and that some day Shahid and his siblings would pay in other ways if she accepted their help. This is how Shahid ended up working as a book binder and in auto repair shops at 14 years old, which exposed him to the harsh treatment of the labor class in Pakistan, on top of the injustice he had already witnessed his mother face as a widow.

“There was a lot of life I saw as a child,” he says. “When you have poor leadership and no political empowerment, these all things give me an inspiration. And that gives me a strength.”

He considers these early experiences an integral part of his social justice training. By 16, he was involved in youth organizing, and since then he has mobilized communities, planned and participated in rallies and other agitations, and worked as an educator in human and civil rights.

“If I couldn’t divert into those things, maybe I become an addict in those days,” he says. “Maybe I become a gangster. These kind of things. But I think I am lucky that society gave me a chance, people gave me a chance, to become a youth activist.”

Shahid put himself through school, including an MBA, and his work in Lahore took him to India, Thailand, and Australia for workshops and conferences. It wasn’t until his move to Brooklyn that he has had to compromise his path, taking on low-wage work for intermittent bouts to get by.

“I came to the US in 2010. I went to Louisiana and spent about two weeks there, but there I was very…”

He stops.

“…because there is no Pakistani community and there is nothing for me, I’m mentally very upset. I don’t know anybody.”

Shahid mimes typing as he tells me he searched Google and found Little Pakistan in Brooklyn and came upon the Pakistan US Freedom Forum. He reached out, and a man named Comrade Shahid (no relation) explained that the area is full of immigrants and the community would be welcoming, but that good housing would be hard to find. When a local Louisiana church organization gathered $165 for Shahid’s Greyhound ticket from Lake Charles to Manhattan, he took it.

When he recounts these days before he arrived in New York, he becomes pensive, hesitant. “So this is how I…” he pauses. “The first night I spend… here on the road, near bus stop, on the footpath…”

He trails off and is silent. By way of explanation, he returns to talking about having to take care of himself as a boy after his father’s death. “Because sometimes when you have these struggles and efforts in your life, you prefer to keep yourself hungry instead of ask anybody.”

Still, Shahid found he had no choice but to accept assistance from the Pakistani immigrant community. He spent his first few months in Brooklyn living out of the office of the Coney Island Avenue Project, a small non-profit run by a man named Bobby Khan (also no relation). But he felt pressure to retain his pride, often pretending to have eaten when Bobby asked if he needed food; there were days he didn’t eat at all.

“I just offered him my space knowing that he didn’t have a place to live,” Bobby Khan said. “He didn’t have any resources. We’re not running a shelter, but you know, as leaders in the community when we see someone in need, if we can do something, we go ahead and do it. More than any type of programming or any official operations, this is something real I can do for somebody like Shahid.”

“ When I go to my room, my apartment, I start crying, shouting, talking with myself, these kinds of things.”

While Shahid prepared an asylum application, he got on his feet by working in construction and restaurants. As he met more people and settled into Midwood, his social orientation reawakened. He saw the need for the type of work he had done his whole life. He talks about how his nook of Brooklyn is shaped by Muslim supremacy, illiteracy, feudalism, rigid ideals about women and girls, and what he calls “brotherism.”

“You have a different class and this is Chaudhary and this is Rajput and a caste system just like home,” he explains. “Little Pakistan is just like big Pakistan. Only difference is this is in America and that is in Pakistan… There is no shortcut, where at USCIS [the federal immigration agency] they have an injection and then they put it in you and it’s, ‘Okay, now you are a good citizen’.”

He simulates giving someone a shot, and chuckles.

“Ting! It is a process, time.”

But getting involved in community work happened in a series of fits and starts for Shahid. He attempted to work with a group that had initially come together in the summer of 2010 to collect and send aid to Pakistan after monsoon floods. Once that emergency effort was completed, however, those who established the organization abandoned any kind of larger mission.

“They said, ‘Fazool! This is a wastage of time to work in community development. This is not the good way to invest our money and time, it’s better to do our jobs and our construction business’,” Shahid recalls.

He too went in and out of construction work, living hand to mouth, losing hours if it rained, sharing a one-bedroom apartment with two others, making barely enough to support himself, let alone send money to his family in Lahore. To add to his hardship, he began feeling symptoms of what he would later recognize as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Sometimes… one or two days, I am unable to go outside from my apartment,” he says, reflecting. “When I sit alone, I feel. I think about everything, my whole situation, my family, my work, my thoughts, my identity. So that’s why when I go to my room, my apartment, I start crying, shouting, talking with myself, these kinds of things.”

He sought out therapists, which he says made him feel more separate from his New York life. The doctors he saw didn’t understand his politics, and Shahid felt they didn’t understand him, making it impossible for him to get the care he needed. When he fell down the stairs in a fog of deep depression in 2011 and broke his leg, and had to quit physical labor, he says he found healing and purpose working with the Allama Iqbal Community Center.

As a Program Director, Shahid raised funds; started a local Urdu language program to bridge the generation gap in families of Little Pakistan; and used his ease with networking to bring attention to Midwood from entities outside Little Pakistan. He connected with his local Community Board, with City Council members, Congresspeople, and more. His efforts garnered invitations to speak at Columbia, Rutgers, and Princeton.

“That was a big success,” he says. “Everybody proud.”

Shahid spent nearly two years at AICC. While much of his work centered on language programs, he continued to try to push a broader progressive agenda for Little Pakistan. Yet despite his accomplishments, some things remained the same.

“Some people, they avoid me on the street,” Shahid explains. “They have a problem with me, like, ‘Oh he’s working with minorities and he’s working with Christians and this and that.’ And I also identified Hindus – Pakistani Hindus – in this community. Nobody knows….. otherwise… otherwise… who gives them work? Untouchable and this and this. That’s why they ask me, ‘He’s a mad. Send him mental hospital’.”

This past Spring, just days after securing a $90,000 grant for the community center – and after getting a grant for almost $100,000 the previous year — Shahid received a termination letter, informing him that the organization lacked the resources to keep him on staff. He was devastated. When his wife and children arrived from Pakistan in August, the responsibility of taking care of his family in such a tough economic and psychological tangle weighed on him more than ever.

The four of them live together in the small apartment off Coney Island Avenue that Shahid previously shared with two roommates. There is little furniture, all donated, and Abdullah, 10, and Mariam, 14, spend many of their afternoons doing homework or watching Urdu programs on Shahid’s laptop in the only bedroom. Of course, as a father, he keeps his stress under wraps as much as possible, figuring out next steps to survive, the only way he knows how.

“I’m not working properly,” he says. “Because I also think that once I start construction work, once I start limousine things, once I start other things, I will be detracked.” He lays out the compromise between family time, and financial obligation, snapping his fingers to punctuate each statement.

“For some money, then I have addiction: okay, work 10 hours, make $100; $100 means $500 per week; spend two days with your family; okay, start a new week from Monday. So it means I wasted my whole life. That’s why I think I have hard days.”

His wife Nazia, he explains, expected something different from America: “Why are you asking me to come here?” he tells me she has demanded. “’I know we have a very bad position in Pakistan, but it is not worse than this… What will be happening? Somebody they kill us? That is better. Here, we are killing ourselves everyday’.”

But Shahid has hope. With a patient smile, he says that things are finally coming together.

Seated on the floor of his living room in front of a suitcase full of papers and files, he produces an IRS document dated September 3, 2014. It outlines approval for tax-exempt status for his own nonprofit, The National Youth Organization of Pakistan.

“There is no shortcut for me,” he says. “So I’m doing my best, but I will get results in the right time… My family, everything, my struggle since 2010, ’11, ’12, ’13, and now ’14 – I didn’t stop my struggle. I’m doing my work, everything. So now I need to wait.”