“Stay with the music, that’s all it’s about anyways.” A night with legendary Chinese jazz pianist Xia Jia.

November 28, 2012

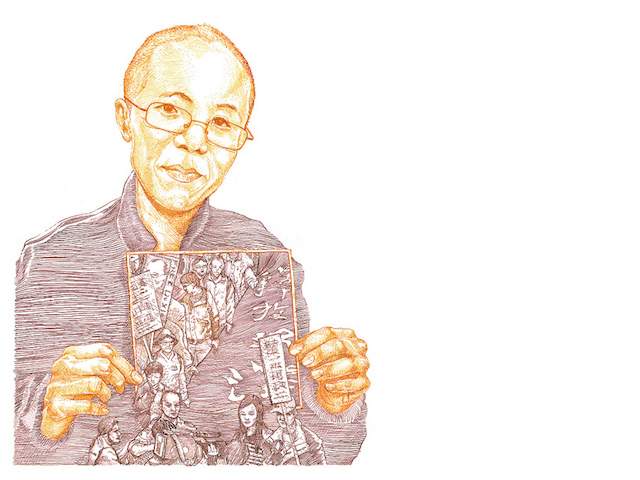

Shanghai’s JZ Jazz Festival is widely regarded as one of the centerpieces of jazz music in China. Held every October, the festival brings world-renowned jazz musicians like Ron Carter and Roy Hargrove to stages scattered throughout China’s top cities. It also provides an opportunity to highlight some of China’s native-grown talent. Xia Jia, a visionary pianist and composer (and a mentor of mine) was among the few Chinese featured alongside American and European heavyweights this year. Xia spends most weekend nights performing massive stadium shows with the legendary “Godfather of Chinese Rock,” Cui Jian (often fondly referred to as “Old Cui”). On this particular Friday night in Beijing, however, Xia Jia reigns as supreme ruler of a smaller, more intimate kingdom.

The East Shore Live Jazz Café sits at the mouth of Houhai, a filthy man-made lake. (I can attest to this: for weeks, a dead cat lay untouched on the ice.) Tucked away in the back of the café, Xia holds court, calmly gazing down at a Yamaha piano through a fog of hazy cigarette smoke that grows thicker by the minute. His hands hover over the keys as he ponders his next move; a cigarette dangles languidly from his mouth. His playing is a fluid mixture of long, pearlescent melodic strands and the toothy grit of the blues. The Xia Jia Trio, which features Japanese drummer Izumi Koga and Xi’an native Zhang Ke on the acoustic bass, performs with a controlled intensity that is worlds apart from the rampant explosiveness of any midtown jam session. In particular, there is something immeasurably precise about Xia’s playing, a calculated rationality that ducks and weaves through the chord changes of each tune.

The trio performs a weekly smorgasbord of jazz standards, as well as a host of original compositions. On a personal level, it was Xia’s own compositions that first piqued my desire to better understand what jazz music meant to a musician who, despite the vast chasm between Chinese and American cultural views, had successfully traversed both worlds.

In between sets at East Shore, I sat down with Xia to learn more about the unique philosophy behind his music. Speaking in various flavors of Eastern and Western philosophy, he reflected on his personal and—by extension—musical evolution. Xia, who grew up in the 1970s, expressed how much that decade affected his approach to music. “Jazz, to me, means freedom,” he declared. Growing up during the Cultural Revolution—a tumultuous period in Chinese history characterized by mass starvation and crackdowns on intellectual dissent—fostered his appreciation for the ability to control the dialogue happening within an artistic medium. “It creates a space for interpretation and personal growth,” he said, though he added a caveat: Most Chinese jazz musicians don’t fully understand the concept of freedom, because the majority of them have grown up without enduring the hardships of the Cultural Revolution. Furthermore, “a wider artistic space requires more structure—neither of which the Chinese inherently understand,” he bemoaned, referencing a concept that many Jazz musicians recognize as key to their musical development. For these musicians, the push for artistic independence by earlier monumental artists (e.g. Miles Davis and John Coltrane) represents “structure”. As musicians remove more constraints from the artistic medium, it is necessary to have a better prerequisite understanding of the historical structure. Xia’s comments highlight that there is limited access to many of these seminal recordings, severely hindering the development of many aspiring musicians in China. As long as this bottleneck exists, Xia believes that Chinese musicians will be stuck in the process of “imitating”, not innovating.

Because of this dynamic, many local musicians still struggle to compete with the monumental American and European figures who tend to take center stage. Xia, who has an established reputation as a musician, believes the only way for Chinese musicians to move forward is to develop a better appreciation for the American jazz tradition and to create a jazz style with unique Chinese characteristics. Some of his compositions fuse Chinese folk melodies with the structural, rhythmic and harmonic framework of modern jazz music. Others are completely original works. Xia’s compositions tend to convey a sense of modernity—the combination of advanced Byzantine harmonies with carefully-crafted rhythmic syncopation creates an effect similar to the rush of balancing on the edge of a cliff: Just when you think you know where the microscopic nuances of the tune are taking you, the piece takes a divergent turn and you find yourself teetering on the brink of chaos. But the macroscopic structure of the revolving jazz form is always there to reestablish musical order.

The core focus in his own music, however, is simplicity, a tenet his mentor and teacher at the Eastman School of Music, pianist Harold Danko, passed down to him. Danko, who spent his younger years touring with the likes of Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan, Thad Jones and Mel Lewis, is considered by many to be an eminent creative voice in jazz music. Danko would push Xia to expand his musical vision beyond the specific context of bebop, blues, and other historical periods: Xia believes that composition is, in part, a post-modern attempt to trim musical ideas down to their basic elements and re-contextualize them to suit his own ear. This is one of his greatest contributions towards building a “Chinese jazz aesthetic,” a unique confluence of harmonic and rhythmic ideas that forge a fresh, alternative path from the “standard” jazz tradition. While it is distinctly Chinese, it also stands in opposition to the stigma surrounding “nationalist” music. Xia’s music is not a mandated Cesarean birth but a nurtured development, established through an acknowledgement of the American jazz tradition, paired with the recognition that his own background, upbringing, and heritage are different.

Back at East Shore, Xia puts out his cigarette and walks back to the piano. He sits down, pauses for a moment, and turns to me, a wide, childish grin on his face. “Stay with the music, that’s all it’s about anyways,” he says, chuckling. Then, without another word, he whips back around and strikes the first chord.