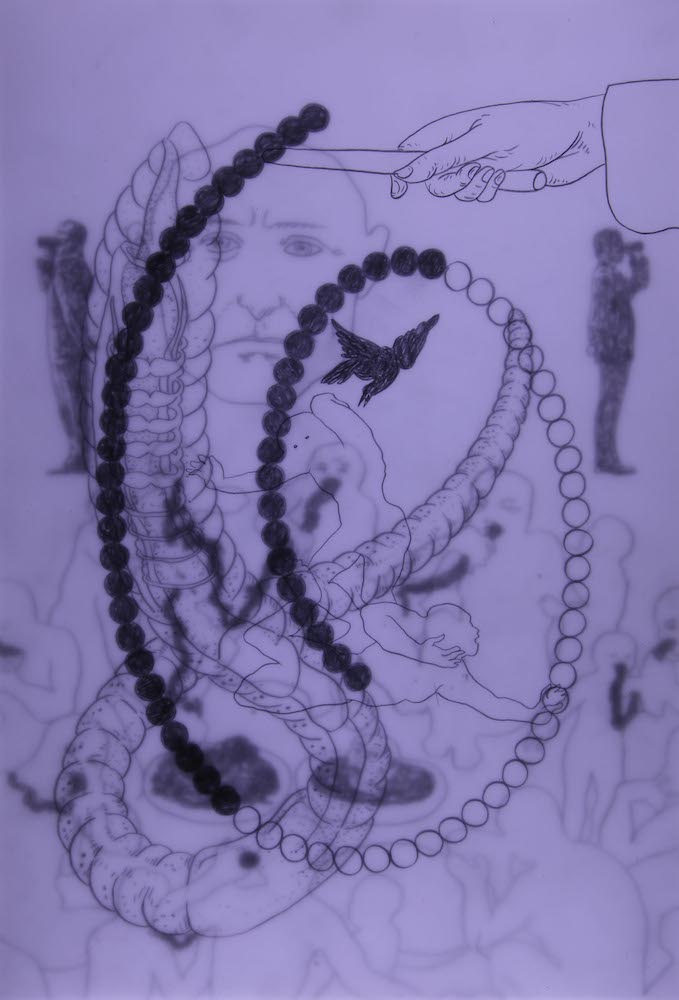

A gathering of Lullabies that swirl in various transitional spaces and threshold crossings, carried by the voices of writers and translators

March 8, 2021

This week marks the one year anniversary of AAWW closing down its New York City office and beginning a period of work-from-home. One year ago, billions of people entered a period of isolation, a period of suspended and manifold grief, a period from which the world has yet to emerge. In this sense, the world lingers in a liminal state: not what it was before, not yet what it will be after.

The lullabies offered in this notebook of the Transpacific Literary Project are in no way a direct response to or reflection on the COVID-19 pandemic. Rather, the lullabies gathered here swirl in various transitional spaces and threshold crossings: a woman’s twilight walk home from work, a mother’s self melted into her baby’s, a baby’s first encounter with earth, a spirit’s waiting for reincarnation, a body’s waiting for its funeral, a body’s physical decomposition, a face’s nighttime disappearance, a dream’s sacred knowledge, a people’s exodus to the sea, and a music’s enduring resistance to silence.

In the tradition of rather dark music, some of the lullabies presented here carry pain and tears. And because sadnesses cannot be (just) written, each text in this notebook of Lullabies is accompanied by the human voice of its writer and translator. The utterances of song, chant, poem, and story allow for their words to occasionally vaporize into the wordless textures of mourning, and possibly radiate a consoling embrace.

***

This notebook is filled with lulling by the following writers:

Shwe Poe Eain, with translation by Maung Day, offers images from a “half-dark | မှောင်တစ်ဝက်” world, “when light is withdrawn from one’s seeing.” This deceptive light of night’s approach illuminates a maid’s walk between the home where she works and the home where she lives, and where her hungry children “frolic inside the palace of their mother’s empty stomach”.

Miaozi, with translation by Pop Bob, sings to her newborn from the place where mother and infant have only partially separate bodies. She sings from her hometown of Jieyang as Hong Kong’s anti-Extradition movement is winding down and as COVID-19 is ramping up. She sings without a husband but married to ten of her friends.

Zed Adam Idris, with a self-translation, embeds a lullaby in the Rawa ritual called jejak tanah, a ritual marking an infant’s first encounter with the land when clumps of earth are rubbed into tiny soles. The ceremony is performed on a strip of yellow cloth laid on the ground that reaches from within the house to the world outside.

Vũ Anh Vũ, with translation by Nguyễn Hoàng Quyên, offers a poem/ script/ libretto in which almost nothing happens except many kinds of breaths. Embodying the drama of meditation, an unconscious rises and offers instructions on how to cultivate “một linh hồn thức tỉnh | an awakened soul”, how to commune with the dead, and how to caress darkness in order to “để phát quang | become a luminescent thing” .

Emil Amir, with translation by Norman Erikson Pasaribu writes of a family who keep their deceased relative’s body in bombo, waiting for years in a casket at home while they struggle to earn enough money to pay his funeral costs. Set in Tana Toraja, Indonesia, amid its growing funeral-tourism industry, the story is wrapped in the pressures of tradition and capitalism.

Trent Walker translates and sings from ក្រាំង, the accordion-folded bark-paper leporello form used for បំពេចុងក្រោយ | end-of-life chants in Cambodia. The Dharma song intends to haunt the living, detailing, in beautifully drawn out melodies, both bodily and spiritual agonies of the passage between worlds.

Yi Won, with translation by EJ Koh and Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, explores the interplay between body horror and innocence, the dissolution of the self, the strangeness of recognition, and a mutilated toy horse.

Kulleh Grasi, with translation by Pauline Fan, writes from the voice of a woven fabric called the pua kumbu, a ceremonial textile of Iban indigenous communities of Sarawak. With the sacred knowledge of the pua kumbu imparted to women weavers in their sleep, dreams play a necessary role in the transmission of material culture.

Ysabelle Cheung speculates a world whose rigid surveillance system and inexplicable disappearances have made life on land so inhospitable that its people organize an exodus to a pocket of the ocean. A lulling song of the sea pulls the inhabitants through a tunneled passageway to reach their exit point, where they may travel (perhaps back) to their watery home.

Mayyu Ali records and translates two Rohingya lullabies sung by mothers as part of his ongoing research and documentation work in Cox’s Bazar refugee camp, seeking to maintain and revitalize Rohingya culture in the face of genocide by the Burmese government. While oral traditions appear to be fading away, these songs of sleep are as vital and inexhaustible as a mother’s love.

***

It’s possible that the lullabies of this notebook might shake up as much as soothe. But perhaps, like after a fit of tearful screams into a pillow, there can be a kind of surrender on the other side of this shaking. And I do hope, with a very long shhhh, that all this leads you somewhere just a bit closer to a deep, good sleep.

Zzzz—Kaitlin Rees