Visitors to the address would have found an entirely different scene ten or fifteen years ago. Before it was a fashion headquarters, the building was a garment factory…

January 7, 2014

On a recent evening in Manhattan’s Chinatown, Canal Street hummed with the usual crowd of tourists and hawkers. Just one block north, on the eighth floor of 148 Lafayette Street, space and quiet abounded. A few solicitous sales people dressed in black moved among racks of bright, modern clothing, attending to a handful of post-holiday shoppers. The 4,000-square-foot concept store for fashion brand Lafayette 148 just opened here last September.

“We want it to feel exclusive,” said Kendall O’Connor, a salesperson at the new store, which is inaccessible from the street.

Visitors to the address would have found an entirely different scene ten or fifteen years ago. Before it was a fashion headquarters, the building was a garment factory, as were most of the neighboring buildings.

“When you walked along the street, you could look up and see clothing hung in the windows,” recalled Margaret Chin, a sociology professor at Hunter College and author of Sewing Women, a book about Chinatown garment workers. “Old manufacturing buildings had huge windows, because that’s where you let in light and air. No one worked at night, to save on electricity.”

(left) A woman in a garment factory on Canal Street, 1979-1982. Courtesy of Paul Calhoun, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

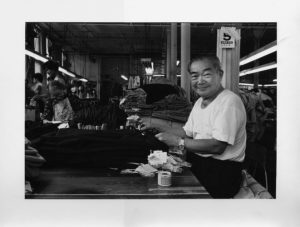

(right) A man working in a garment factory on Canal Street, 1979-1982. Courtesy of Paul Calhoun, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) Collection.

In those days, Chinatown’s garment factories employed tens of thousands of workers, most of them Chinese immigrant women. Since the 1980s and 1990s, the combined forces of global outsourcing, the post-9/11 economic downturn, and gentrification have largely wiped out the garment factories that once dominated the neighborhood. In their stead, Chinatown is now home to trendy boutiques and high-end fashion brands like Alexander Wang and Derek Lam. Many of the former factory buildings are now luxury condos. Their presence is both a tribute to the community’s manufacturing past and a sign of the gentrification and other factors that helped kill it. These contradictions are especially embodied in Lafayette 148, an unusual company with a history that tells the larger story of manufacturing in Chinatown.

The garment trade helped build New York City. It began in the 1850s in the tenements of lower Manhattan, with mainly Jewish and Italian immigrants working from home. The growing industry spread north and west through the early 19th century with the establishment of proper commercial and retail spaces, and solidified into the midtown Garment District during the 1920s. It began moving back downtown again, to lower-cost areas, after World War II, and reached its height in Chinatown during the 1980s, according to Margaret Chin, whose own mother and aunts were Chinatown garment workers. She estimates that there were 500 garment factories employing 20,000 workers, most of them Chinese immigrant women.

One of those factories stood at 148 Lafayette Street, and was owned by Shun Yen Siu. He came to the US in the late 1960s while in his 20s, and over the decades worked his way up from a garment worker. By the 1970s, he owned several factories, some manufactured clothing for brands like Anne Klein and Burberry.

“There was a mouse problem and we kept cats on every floor,” recalled Hoi of the company’s early days. “One of them slept in an inbox and once presented a mouse to Deirdre.”

One day during the mid-1990s, he and several fellow contractors found themselves with an excess of fabric, according to Tom Hoi, a company spokesperson. Siu suggested that they make jackets and sell them at 3 for $100, and “despite minimal advertising and presentation,” as Hoi put it, they sold out. This gave Siu the “confidence” to start his own brand in 1996, alongside his wife Ida Siu and co-founder Deirdre Quinn. Their investors were all Chinatown contractors like Siu.

“There was a mouse problem and we kept cats on every floor,” recalled Hoi of the company’s early days. “One of them slept in an inbox and once presented a mouse to Deirdre.”

Since then, Lafayette 148 has grown from 15 to 1,600 employees, and is sold online as well as in 400 stores across North America, including Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdale’s. A jacket of theirs can cost around $600; a sweater, $300. Crain’s New York Business listed the company at number 10 in a 2012 list of the New York area’s largest minority-owned businesses, with revenue of $136.5 million. In September, the New York Times called them “one of fashion’s quietest success stories.”

However, the success of Siu and his fellow contractors is an exception, rather than the rule. Very few of the old Chinatown contractors have been able to stay in the neighborhood, or in business.

Some of the business’s decline can be attributed to changes in immigration patterns.

“The industry grew probably due to increasing immigration after 1965 [when new laws opened the US to Asian immigration]. People needed work, and family networks and word of mouth led to the garment industry in Chinatown,” said Chin. “By the 1980s and ’90s, the stream of immigrants was becoming more diversified and not mostly working class, so not everyone coming over was going to the garment industry. Plus, women who had been there since the ’60s and ’70s started retiring.”

And of course, the Internet and easier communications ushered in the era of overseas manufacturing, which also took its toll on Chinatown. But, what had been a slow decline was drastically accelerated by 9/11.

Order fulfillment became almost impossible. Roads and subway lines were closed throughout Lower Manhattan. (One major thoroughfare, Park Row, remains closed to this day.)

“Half the workers lived outside Chinatown and couldn’t commute to work. A lot of owners didn’t live there either,” said Chin. “Even people who lived there, they went to the factories and there was no electricity or phone service.”

On the morning of 9/11, 250 garment factories employing 14,000 workers existed in Chinatown. By 2004, said Chin, 100 factories had shut down, and with them went 6,000 jobs.

Meanwhile, the holiday rush was imminent. So, Lafayette 148 did what many fashion companies, from Prada to Donna Karan to Ann Taylor, did: it outsourced the work overseas. And, it never came back.

Advances in inventory management technology meant that companies could make do without the “quick time,” or fast turnaround work, for which they had relied on Chinatown, said Chin. Even if they wanted to come back, the workers were no longer there. Some retired, others found new jobs as restaurant workers or hotel maids, and some, seeing the writing on the wall, entered job training for jobs in home health care, Chin found.

“Factory owners desperate for workers have resorted to taking out full-page want ads in the city’s Chinese newspapers with minimal results,” reported Daisy Hernández for the New York Times in March 2003.

On the morning of 9/11, 250 garment factories employing 14,000 workers existed in Chinatown. By 2004, said Chin, 100 factories had shut down, and with them went 6,000 jobs. Gentrification and rising rents put still more pressure on those that remained, and in the intervening years, more closed down or moved to the outer boroughs. A few factories remain today – to get by, some of them rent out corners to small designers and other companies – but large-scale garment manufacturing is virtually nonexistent in Chinatown.

People tend to think of garment factories as grim sweatshops, but Chin maintains that the jobs were actually highly desirable for legal immigrants who did not speak English. The wages, while low, did allow them to eventually buy homes in Brooklyn or Queens. And the hours were flexible, she said, because the Chinese-owned factories worked on a piece-rate system rather than the hourly wage structure that predominated in the Garment District. This made the work attractive to mothers.

“Women could come to work, leave to pick up their kids from school, and come back in the evening,” said Chin. “One worker told me, ‘This job is for mommies.’”

In the two years after 9/11, the average household income of the roughly 70 workers Chin interviewed had nearly halved, to an average $16,000 per year. And because many of them lived in Sunset Park and Flushing, their loss of income affected businesses in outer borough Chinatowns too.

In the case of Lafayette 148, after 9/11, Siu turned to factory contacts in his hometown of Shantou, China. The next year, the company decided to establish its production headquarters there. Siu moved back to China, and the state-of-the-art factory, a centerpiece of the company’s philanthropic and marketing efforts, opened in 2008. Today, 1,300 of the company’s 1,600 employees are in China. And increasingly, China is a target market for the brand, as it is for many other fashion companies. Lafayette 148 opened a Shanghai store in 2012, a Beijing one in 2013, and has two more planned for other Chinese cities.

Surely, none of the former Chinatown workers that Margaret Chin studied could have imagined that when they left China for the US decades ago, their jobs would eventually cross in the opposite direction. Nonetheless, Chin does not see the tale of the garment industry in Chinatown as an unhappy one.

“Usually when countries start entering global trade, it’s through manufacturing. We’re now beyond that in the US, so the shift here is more towards knowledge-based work like design,” she said. “I think it is inevitable that we lose large-scale manufacturing.”

Surely, none of the former Chinatown workers that Margaret Chin studied could have imagined that when they left China for the US decades ago, their jobs would eventually cross in the opposite direction.

Speaking in Chinatown at a Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA) talk a few months ago, a representative from Lafayette 148 pointed to what she felt would be the future of fashion there.

“This neighborhood – the lines have blurred between Chinatown and SoHo – has seen so many fashion brands and showrooms moving down here, in addition to the rapidly growing fashion retail scene,” said Debra Clark, senior vice president of marketing. “The fashion industry will continue to thrive here, but in this different form.”

Many of those brands, like Alexander Wang and Derek Lam, which are based in the area, and Vivienne Tam, which has a store in Chinatown, are helmed by Asian-American designers. Fashion boutiques Opening Ceremony and Creatures of Comfort are there too, and also helmed by Asians. Their ascension in fashion is meaningful to their adoptive neighborhood. A recent MOCA exhibition on Asian-American designers was such a hit that the museum extended it for several months.

During an interview about that show, the museum’s curator Herb Tam told Open City, “For the local Chinese community, there’s the clear connection to garment work in the past.”

But as the neighborhood changes, rents continue to rise. Last October, Matt Chaban reported in The Daily News that the singer Rihanna was renting a penthouse at 129 Lafayette, another former garment factory just a block from 148. The huge windows that used to let light and air into the factories now make them highly desirable loft spaces, said Margaret Chin.

In 2007, the 148 Lafayette building was sold and the rent “went way up,” said Tom Hoi. The company considered moving. But it decided to stay, and Hoi says it remains invested in the neighborhood.

“We are very serious about being a part of Chinatown – its history, present and future. We are also a part of Chinatown’s evolution,” said Hoi. “Chinatown is involved in every facet of the fashion industry, no longer just making garments.”