A community’s struggle to define and uplift the legacy of Malcolm X.

September 25, 2018

“We come as descendants of our ancestors. We come occupying a place in time and space in order to honor that which is best within ourselves. We come as elders. We come as children. We come as youth.”

— Imam Talib Abdul-Rauf

Imam Talib Abdur-Rashid addresses the crowd, his words intermingling with the thunderous impact of rain on umbrellas.

“We thank God for giving us the strength and health to be present today, and we must be present today, because we are not fair-weather revolutionaries. The struggle for revolution does not just occur when the sun is shining.”

Before him stand eight men in a rectangle formation facing one another, their all-white thobes and turbans now translucent, their rain-soaked faces solemn. A red, black and green flag lies on the grass between them, along with two chairs, one cloaked in white, another in the RBG. Thrones for a King and Queen.

An embossed bronze plaque on the ground nearby reads “Hajj Malik El Shabazz,” and in smaller letters – “Malcolm X” and “Betty S.”

***

It was the kind of day that defied expectations, dedicated to a man who did the same. The early beginnings of summer in New York City, those rare, fleeting, magical moments of sunshine and joy before the humidity sets in, suffocating everything and everyone in its path. It should have been one of those days.

Instead, I found myself standing on the corner of 116th and Lenox at 9 a.m. in a long-sleeved jumpsuit, boots, and down winter coat, fur-lined hood pulled up as the first (of many) drops began to fall from a somber, colorless sky. I waited. Nothing came. Where was everyone? It was now 9:30. I grew anxious.

Finally, a young couple stepped out of a taxi, umbrella overhead. I could tell that we were most likely going to the same place. I could also tell that they were converts to Islam. The young man stood tall, wearing a fitted kufi, pants that just barely skimmed the ankles, and mustache-less beard; his wife in long black skirt, black hijab and over-sized coat. I approached them with Assalam Aleikum, asked if they knew where the bus was, and we quickly became friends, sharing in our mutual confusion.

As the rain intensified, we stood under the awning in front of Masjid Malcolm Shabazz, formerly Muhammad Mosque No. 7, the historic Harlem mosque that once housed a young minister named Malcolm. We made phone calls and asked inside – nobody seemed to have a definitive answer as to when or where this bus was arriving. Eventually I ran back to the source — the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood (MIB) on 113th and St. Nicholas.

I arrived in time to see two men leaving the mosque — a tall, imposing Caucasian man with a full, snow-white beard and matching hair (I later heard some of the others call him “Snowman”), and a much younger man, possibly his son, both cloaked mostly in white. Relieved, I joined them as they headed towards the meeting spot on 116th, learning they were part of a group of regulars, who came every year from out of town specifically for this occasion. These particular men were from the Pittsburgh contingent (home of my alma mater), but there were also a handful of people from the Bay Area, in addition to the MIB regulars.

“A lot of people think about Malcolm X as this isolated, larger-than-life, almost mythical figure, as if the ground opened up and Malcolm X emerged. But he was actually influenced greatly by the people around him.”

On the bus ride up to Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, NY, the final resting place of El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, or Malcolm X, and his wife Betty, Snowman spoke to me about what to expect of the day. I was one of only three women on the bus, the only single woman and one of the few newbies; Snowman recognized this and took it upon himself to make small talk.

“A lot of different groups come to pay their respects to El-Hajj Malik and Betty Shabazz, not just the Muslims,” he told me. “You’re going to see lots of different rituals and practices — it can be surprising if you’re not used to it.”

Snowman was referring to the annual visitation — a pilgrimage of sorts — to the grave of Malcolm and Betty Shabazz, a ritual that has taken place on May 19, Malcolm’s birthday, every year since his death 53 years ago. The pilgrimage is organized and led by the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), a Pan-Africanist organization founded by Malcolm X in 1964, only eight months before his death. On their Facebook page, they write:

“The O.A.A.U. initiated the pilgrimage in 1965, after the burial of Malcolm X, to honor and show respect for our people’s fallen leader as well as to educate future generations about the legacy of Malcolm X and his effort to liberate African People’s minds and bodies. The ceremony was designed by Sister Ella Collins, the sister of Malcolm X, then President of the O.A.A.U., and was directed by her until Brother James Small, Brother Willie Stark and her son, Rodnell Collins, were appointed to continue the pilgrimage.”

On the bus, Imam Talib Abdur-Rashid, standing Imam of the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood, tells us about some of this early history – of the mosque, of the pilgrimage, of how the Muslims started participating in this annual event. Strong, steadfast, focused and authoritative, Imam Talib is not one to mince words and enjoys setting the historical record straight.

He tells me that for a long time, the Muslims were not a part of the annual visitation, called “ziyarah” in the Islamic tradition, due to ideological disagreements over the idea of a “pilgrimage” in reverence to an individual, rather than God. The more hardline, conservative positions on the matter came when men from the community began traveling overseas (mostly to Saudi Arabia and Egypt) to study Islam. As Imam Muhammad Adeyinka Mendes, now one of the leaders of the Muslim delegation, writes in his account of his first time participating in the ziyarah:

“Why would so many cultural nationalists, Afrocentrics, socialists, Christians, and others who did not share Malcolm and Mother Betty’s spiritual tradition be in attendance while those who did were hardly there? This mystery was solved by an elderly Muslim gentleman whom I met at a Spring Valley halal restaurant offering Mediterranean fare. After giving the greetings and some small talk, I divulged the purpose of my visit to New York, and he told me, “Yeah, there used to be a time when thousands of Muslims would visit Ferncliff on May 19. People would come from everywhere. There were so many cars that if you didn’t get there early enough you couldn’t park anywhere in the cemetery.”

“What changed?” I asked.

“Well, it hasn’t been that way since the 80s. You know, brothers started going overseas to study the Deen [religion], came back, forgot who they was, and told people it was bid’a [a religious deviation]. So Muslims stopped coming and our numbers just kept getting smaller and smaller.”

So for many years, the OAAU, the Sons of Africa, and a number of African religious groups made up the majority of attendees. Until the early 2000s, when a young Muslim leader named Shaykh Abdul-Quddus, a former member of the Sons of Africa, one of the main pan-Africanist organizing groups, decided to begin attending the annual event as the Muslim representative. An educator and martial artist, Abdul Quddus was a role model in the community and carried the responsibility of representing MIB with dignity and grace. It wasn’t until he was murdered while trying to break up a fight at a bodega in Harlem several years ago that Imam Talib and the delegation from MIB began to make the annual trip.

“Militant Malcolm, Muslim Malcolm, Internationalist Malcolm. I think about the power that lies in a life-changing legacy that creates space for so many, but also the contention. What does it truly mean to carry on Malcolm’s legacy?“

The young man who shot Abdul-Quddus got life in prison. “Two lives taken,” Imam Talib says. “For nothing but stupidity.”

Within half an hour we arrive at the cemetery, the bus parks, and we wait. Outside, the rain intensifies, hammering down on the groups of men and women singing, chanting, drumming. A tall, authoritative man boards the bus to let us know it would be about an hour before the program begins.

Imam Talib tells us that this is Professor James Small, the respected elder, or “Baba” (a Swahili term of respect meaning “father” that became popular among the Black Panther Party and Pan-Africanist community) who helped establish the pilgrimage 53 years ago alongside Malcolm’s sister, Ella Collins, for whom he served as a personal bodyguard.

After Malcolm’s death, Baba Small took over as the Imam of the Muslim Mosque Inc., the Sunni Muslim organization Malcolm founded the same year as the OAAU, after his departure from the Nation of Islam (NOI) and conversion to Sunni Islam. It is the members of this organization who formed the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood that stands today, a space considered the “lineal descendant” of Muslim Mosque Inc. – and whose members see themselves as the direct descendants of Malcolm X.

Outside, the air smells of water and earth and prayer. I get off the bus and wander. Elaborate painted faces, ankh necklaces, black power fists, dashikis and head wraps, turbans and hijabs, prayers and invocations and drum circles. The wind renders umbrellas useless and the sky commands respect.

I can’t help but feel that there is something otherworldly about this day. In Islam, as in many other faith traditions, rain is seen as a blessing and life-giving force from God. The skies are open and, it is believed, particularly receptive to prayers during times of rainfall. This inexplicably torrential day, in the middle of May, also happened to fall this year during the month of Ramadan, the holiest month of the Islamic calendar, a time of reflection, gratitude, discipline, and fasting.

This is not lost on the day’s speakers, many of whom note the beauty and the blessing of this day. As Baba Smalls notes, “This is a time of the year when great cleansing takes place — spiritual and physical. Introspection, contemplation, all of that happens in the process of Ramadan.”

***

Following Imam Talib’s opening remarks, a young Imam named Abdul Rauf takes the mic to recite a poem about Malcolm’s life and legacy. Referencing influential figures in Black history, he situates Malcolm in the larger story of black nationalism and afrocentrism in this country, paying homage to those who laid the foundations for black liberation.

“El Hajj Malik, what is the secret of your legacy? By Allah you fulfilled a part of destiny. Resurrecting the mighty people of antiquity. Reconnecting us to the best of our ancestry. Reconnecting to long lost family. Rejecting mythology for spiritual purity. Fulfilment of your forefather’s goals. You went to Africa where Mosiah Garvey couldn’t go. You brought back Quran and traditions Noble Drew Ali didn’t know. Completing a bridge to our ancestral home,” says Imam Abdul Rauf.

“In his final years, Malcolm embraced Sunni Islam, but the ideology he would have aligned with is today the subject of intense debate, with observers projecting their own predilections onto his imagined trajectory.“

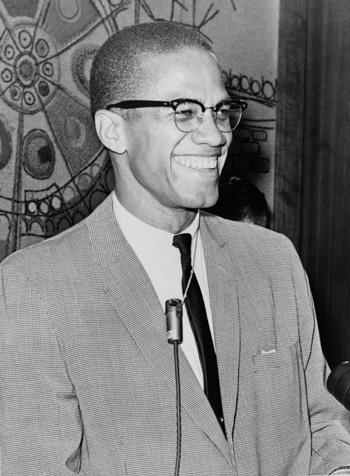

As Katie Merriman, a PhD student in Islamic Studies who runs the Muslim History Walking Tour of Harlem, observes, “A lot of people think about Malcolm X as this isolated, larger-than-life, almost mythical figure, as if the ground opened up and Malcolm X emerged. But he was actually influenced greatly by the people around him.”

Malcolm would not have been Malcolm had it not been for the influence of people like Marcus Garvey, the pan-Africanist leader who promoted a return of the African diaspora to their ancestral homelands (and who found a staunch supporter in Malcolm’s father), and Noble Drew Ali, founder of the Moorish Science Temple of America, the first Islamic organization in America and predecessor to the Nation of Islam.

As I look around at those in attendance and listen to speeches from priests, imams, Afrocentric and black nationalist activists, I think about the complexity and diversity of this legacy. I think about all the different people and traditions who lay claim to this legacy – those who see Malcolm as a Black nationalist above all else, or as a Muslim first and foremost, who amplify or downplay certain aspects of who he was. Militant Malcolm, Muslim Malcolm, Internationalist Malcolm. I think about the power that lies in a life-changing legacy that creates space for so many, but also the contention. What does it truly mean to carry on Malcolm’s legacy?

Later, when I tell (non-Black) Muslim friends or family about the event, they are surprised to hear that so many non-Muslims were present. “Isn’t Malcolm… ours?” An Arab-American friend remarks that, growing up, she never really thought of him as a civil rights leader, but as a Muslim figure who did a lot for Islam in America. “We think of what he did for us and our community, what he did for the image of Islam.”

In the Muslim spaces I often inhabit – dominated primarily by Muslims of Arab and South Asian descent, the names of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X are often noted as Muslim icons, examples to be emulated. But they are sometimes stripped of their context, their complexities, their contradictions, their histories, and sometimes, their blackness; sanitized and packaged as Muslim only, or Muslim primarily. To hear that he is also revered and claimed by polytheists, atheists, communists, Black nationalists, is striking to people who, perhaps subconsciously, have come to see him and his legacy as one-dimensional.

Hisham Aidi, professor at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, describes this tension in an article for The Nation entitled “The Political Uses of Malcolm X’s image.”

“In his final years, Malcolm embraced Sunni Islam, but the ideology he would have aligned with is today the subject of intense debate, with observers projecting their own predilections onto his imagined trajectory,” Aidi writes.

He notes that the image many Muslim community leaders hold of Malcolm is that of “a stunningly self-disciplined and self-abnegating individual, who stands as a testament to the power of Islam to inspire and rehabilitate,” despite his personal diaries that reveal a more nuanced individual who occasionally enjoyed “being away from his role as a religious leader, and away from religious strictures as well.”

***

Throughout the ceremony, when introducing representatives from the various faith and cultural traditions present, Baba Small gives nods to the diversity among the crowd:

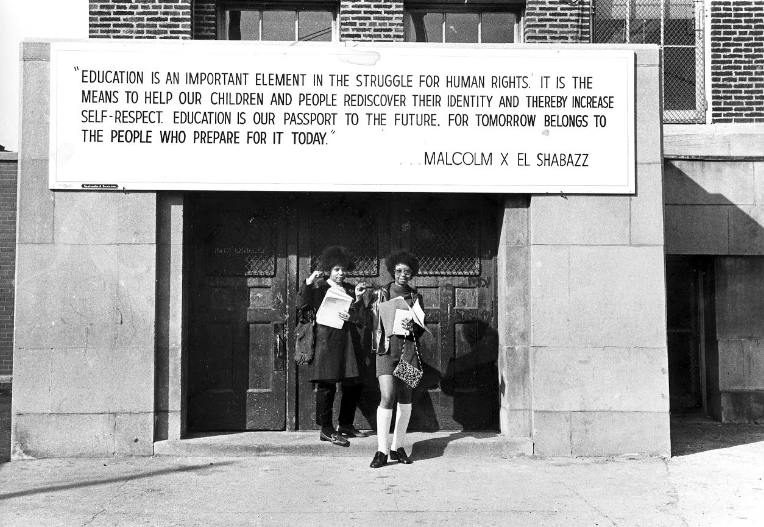

“You see a lot of spirituality and religion in this ceremony but this is not a religious ceremony. But, religion is a part of our culture and life. Islam was Malcolm’s chosen spiritual tradition, so they [the Muslims] open it up… In our tradition, we have many traditions. Malcolm was a pan-Africanist and a Black nationalist. And he said out of his own mouth, ‘I’m a Black nationalist freedom fighter.’ And he defined that nationalism to mean that you own the land, the business and the resources where you live. And so all of our people are included in this ceremony, and all of our traditions that want to come forth, we try to include in the ceremony.”

In a seeming acknowledgement of the varying visions of Malcolm’s legacy and an understanding that these sometimes stand at odds to one another, Small is sure to remind the attendees of the underlying unity beneath the labels.

“We have many traditions… So don’t get carried away with ‘I’m Kemetic, I’m Yoruba, I’m Akan.’ It’s just Black folks with pretty labels. And it doesn’t mean much unless you’re willing to do what he did… If you’re not willing to do that, your religions don’t mean nothing. The price of freedom is death, and then he proved it. Thirty-nine year old kid changed the world.”

One by one, the speakers give blessings and prayers upon Brother Malcolm, note his courage and sacrifice, and speak of how we best honor him – by continuing the work, continuing to fight for the liberation of black people. But what that fight looks like, what form it takes, still seems somewhat nebulous.

Every year, a member of Malcolm’s family is invited to speak at the ceremony. This year, it was his grand nephew, a high school science teacher from Boston, who spoke of an intellectual struggle – to decolonize the mind and recognize the internal fortitude within:

“Uncle Malcolm said we have to separate ourselves from this colonialist mindset, this institution. And he didn’t only mean in the body, he meant in the mind – the philosophy, the ideology, the methodology… The experience from our DNA, from where we came as original people. That’s enough to take us where we need to go, that is enough to bring us out of this darkness that this institution has been trying to perpetuate on us.”

Brother Michael, a representative from “100 Blacks in Law Enforcement Who Care,” an internal relations advocacy group that speaks out against police brutality, racial profiling and police misconduct, shares a concrete example of how to continue Malcolm’s work – by protecting one another.

“All of us are here to honor Malcolm. When we honor Malcolm, we honor the best in ourselves. While we’re doing that we must continue to protect black men. There are too many of us being killed on our way to school, on our way to work, on our way home. What better way is there to honor brother Malcolm than by protecting each other?”

“[The annual pilgrimage] is a declaration that a legacy of uplifting the downtrodden, speaking truth, and fighting for unequivocal justice and liberation from oppression, is a legacy that makes room for all.”

And a woman representing the Jericho Movement, an organization that works for the rights and freedom of political prisoners in the United States, spoke of honoring the civil rights leader by supporting political prisoners, like the 13 members of the Black Panther Party who remain in prison “for carrying on the work that Malcolm spoke of.”

“If it’s going to visit, writing a letter, sending commissary money, finding out what their family needs – everybody can do something… We have an obligation to honor the people that sacrificed their lives and their freedom,” she said.

***

After the main ceremony wraps up with the folding of the red, black and green pan-African flag, the crowd disperses, and the Muslims stay behind to read Quran and pay respects according to Islamic tradition.

This moment is quieter, more reflective. Our time alone with Malcolm. Though I sense a hint of tension, that tug-of-war over Malcolm, when I overhear one of the attendees remark as she departs, “they have to do their Muslim thing now.”

Imam Talib addresses the now much smaller crowd:

“It’s important, not only for us as Muslims, but as you saw by this large gathering in the rain, and the gathering gets larger every year – people come out, they bring their children, they bring their teenagers, in order to impress upon them the importance of the values that this brother and his wife stood for. So it is vitally important that we maintain the tradition, first of Islam, of praying for our ancestors, praying for our family, and it’s important for us, as freedom-loving African people, that we keep the memory and legacy of El Hajj Malik El Shabazz.”

Imam Adeyinka Mendes leads us in a recitation of Surat Yaseen, the 36th chapter of the Quran, referred to as the heart of the Quran.

On the bus ride back, we speak about Malcolm, the Nation of Islam, the ways in which such black nationalist and pseudo-religious movements paved the way for hundreds of thousands of African Americans to find their way to Islam. I am struck by how, for many, reading the Autobiography of Malcolm X is the starting point of their journey with Islam, following his trajectory through the Nation of Islam to Sunni orthodoxy. Snowman remarks that, for all the talk about continuing his legacy, that’s all it is – talk. “No one is actually doing the work that Malcolm did,” he says.

I continue to reflect upon my own shifting notions of who Malcolm was and what his legacy really means. Having been exposed in many Muslim spaces to narratives about Malcolm the redeemed, the transformed, the man who rose above a troubled past to become the quintessential Muslim freedom fighter and martyr, I had not realized the ways in which this narrative was an erasure of so many others.

An elder member of the Mosque of Islamic Brotherhood, when speaking to me about Malcolm, recalls the confusion and devastation among members of the Nation of Islam upon Malcolm’s conversion to Sunni Islam and subsequent shift in ideology. There were those who thought that he had been brainwashed, who felt a betrayal of Black nationalist ideals – that his conversion, from the hardline NOI position against white America to an Islam that preached racial equality, had softened or diluted his radical dedication to Black liberation. Perhaps, to some, these Malcolms seem irreconcilable.

But to me, the annual pilgrimage to his grave is an attempt to reconcile Muslim Malcolm, Militant Malcolm, and all the Malcolms in between. It is a declaration that a legacy of uplifting the downtrodden, speaking truth, and fighting for unequivocal justice and liberation from oppression, is a legacy that makes room for all. “In our tradition, there are many traditions.”