A man in search of his ex-lover looks back on his coming of age—from Manil Suri’s pre-apocalyptic novel set in Mumbai

June 19, 2013

At the opening of Manil Suri’s “The City of Devi”—the final book in Suri’s loose trilogy of novels whose titles reference Hindu gods—India and Pakistan are on the verge of a nuclear war following a series of cyber-terrorist attacks. The city of Mumbai has all but emptied, but Sarita remains, searching for her husband Karun, a physicist who has been missing for more than two weeks. Sarita is not alone. Ijaz, a confident young gay Muslim man who goes by Jaz, has joined the search. He, too, hopes to reunite with Karun, his former lover. In this excerpt from the novel, we get to know Jaz more intimately, as he recounts his early sexual encounters and travels across the world.

Perhaps it’s a fin du monde thing, but I have this sudden overwhelming urge to begin drafting my memoirs. The heartwarming saga of little Jaz who came of age around the globe. Our story begins way back in 1581, when the Mughal emperor Akbar simmered together equal parts of Islam and Hinduism (with a pinch of Christianity thrown in) to rustle up his own curry religion, “Din-i-Ilahi,” or “Divine Faith.” The concoction didn’t quite take—at least not until centuries later, when my parents had the brainwave of updating the recipe for modern tastes. They used Akbar’s principles to formulate a version of Islam that could peacefully co-exist with other religions (or so they claimed). An Emperor’s Bequest to Islam, their joint 1,300-page doorstopper, spent twenty weeks on the New York Times bestseller list in hardcover alone. The fact that they remained practicing Muslims (albeit the liberal, wine-guzzling kind) put their message in high international demand. Here was Yale luring them back to America with the promise of dual professorships on my sixth birthday. Two years later, the king of Bahrain offering pots of money to come shore up his liberal credentials. An instant appointment in the latest European country (Germany, Holland, Switzerland) wanting to prove its open-mindedness after passing some blatantly discriminatory law against Muslims. And after the Arab Spring, even Qatar and Saudi Arabia stood in line to have their blemishes airbrushed, their repressive images tamed.

Inflamed with the desire to change the world, my parents moved so much that I felt I lived in a washing machine. Each time I tried to fit in with a new culture or skin tone at school, the spin cycle came on. Human connections seemed pointless, lasting only as long as we remained in town. My sense of estrangement was the only constant, following me like a dependable pet across the years and continents. I felt so hopeless, so in thrall of a mushrooming interior darkness, that my company turned even the most misfit of my fellow students off.

At the time, I didn’t realize that a deeper reason for my malaise lay hidden, something more incendiary than just our frequent relocation. My mother and father remained oblivious—beyond food, shelter, and clothing, they possessed only a hazy awareness of what other nurturing parenthood might involve. The fact that I found it impossible to get bad grades meant my school performance never cued them in on how little I worked or how despondent I became.

In Geneva, on my fourteenth birthday, I straightened out a paper clip and stuck it through my tongue. Then I tried to pierce the end back through again to form a ring, but couldn’t, because of all the blood. I wiped my lips clean and returned to the dining table, where my parents waited, editing book proofs and sipping gamay. Mouth closed until the last instant so nothing dribbled out prematurely, I blew out the candles on my birthday cake.

That finally got their attention. The white of the whipped cream icing provided just the right foil to give the red I contributed a breezily decorative effect. Once we returned from the emergency room, my parents began to notice other things as well—the anti-Arab posters nailed to my wall, the swastika imprinted on my neck, the razor blade by my bed. I listened to them talk late into the night, their shock permeating through the wall. What an amazing notion that all that jetting around may have fucked me up!

Their solution was to move once more. To Mother India this time, which would unscramble my identity, fill my heart with pride in who I was, where I came from. That’s how the young and still impressionable Jaz found himself sitting in the green-walled annex to the Byculla mosque in Bombay, fitted with a skullcap and equipped with a Koran. Each evening, as the adults prayed upstairs, I stared at the paint peeling off the benches, trying to tune out the hadiths being explained by the imam. Could I escape again by piercing some other body part?

Fortunately, my cousin Rahim, who attended the same class, had alternative plans for my edification. My parents, ever pressed for time, arranged for me to spend the evenings at his home afterwards. At sixteen, Rahim not only exceeded me in age but also in girth—I experienced his weight firsthand, each time he sat on me at the end of our wrestling bouts. He insisted we strip down to our underwear like Sumo wrestlers—his sweat marked my body, smelling of whatever spice lingered most dominantly from lunch.

Rahim’s mother had died a decade ago, and his father worked late, so we didn’t have to worry about anyone supervising us. Soon we were undressing completely and wrestling in the buff. I’m not sure if my technique improved or if Rahim simply let me, but I started ending up on top more often than not. My thighs straddling his hips, my seat pressed into his crotch—even though I left his hands free, he never pushed me off. One evening, I had the bright idea of slapping him in the face with my penis as we horsed around. He looked at me strangely, then leaned forward and took me in his mouth.

For an instant, I hung there, suspended over him in alarm. Then I felt someone older, more experienced, take over. This person seemed conversant with the geography of Rahim’s mouth, seemed to know just how fast and how deep to thrust, and how much to pull out. I found my neck arching back, my hands grabbing Rahim’s head as he made soft grunting sounds. Perhaps the person was not as experienced as I thought—before I could stop myself, I had transacted my first orgasm, with my cousin’s mouth.

Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, survivors of the coming October 19 holocaust or future alien voyagers: this is where my journey takes its most dramatic turn! The before and after, the B.C. and the C.E., the divine revelation that swept away all my baggage from the past. Suddenly I didn’t feel hopeless, suddenly I found myself in control, suddenly the answers to all my questions popped and burst like fireworks. My identity flashed on, my confidence powered up, the path to my fulfillment in life blazed in the sun.

Over the next few weeks, Rahim and I poked and probed and plumbed. We matched appendages to orifices in every combination that sprang to our fevered minds. Dispensing with the wrestling, we dove directly each evening into racking up the notches on the bedpost (not to mention the sofa, the dining table, the kitchen stool, even the telephone stand, before it broke). The arduousness of some of our experiments eased appreciably when we discovered the lubrication properties of pantry ingredients. (Jam was too sticky, butter worked better than mayonnaise, but nothing rivaled the glissance of pure ghee.)

My parents couldn’t stop beaming—how eagerly I trotted off to class every evening, how well their mosque experiment seemed to be working. (They even published a paper on this, “Therapeutic self-affirmative effects of religious instruction on troubled youth,” soon after.) The fact that I’d begun paying attention to my physique was an added bonus. “Healthy mind, healthy body—just like the Book says,” my father remarked, each morning he saw me performing calisthenics. In reality, roles had begun to emerge in my after-curricular activity— clearly, I was the boinker, Rahim the eternal boinkee. If I wanted to fit my emerging self-image, it behooved me to start pumping up.

A year and a half later, little remained of the boy from Geneva with the paper clip in his tongue—in his place stood the Jazter, virile, self-assured, buff (not yet, but working on it). Buoyed by my recovery, my parents again succumbed to wanderlust. Rahim had become too attached, boinking him too rote, so I felt ready to move on as well. What better place to complete my education than the great cruising expanses of America?

We ended up in Chicago. It didn’t take long for me to notice the line of men lounging in their cars (all potential teachers) as I skateboarded past after school in Lincoln Park. Some of them took me along to the baths near the Loop, where I tried out threesomes and foursomes, to see how high I could go. The conspicuousness of my skin tone (which, while never debilitating, had often made me self-conscious in school) worked wonders for the trick count—I even switched y’s and w’s to accentuate my South Asian origins. Occasionally, high on Quaaludes, I spent a Sunday afternoon romping with the runaways at the bird sanctuary (even at my most stoned, though, I took care to protectively glove the Jaz-in-the-box). On a trip to San Francisco with my parents, I sneaked out to an all-night orgy in the Castro, making them wonder the next morning what had tired me so. As a side benefit to all these extracurricular opportunities, I felt easier and more relaxed around my classmates—in fact, I even initiated a few.

The two years I spent in the U.S. were like finishing school. I learnt etiquette and protocol, the right amount of sauna small-talk (both before and after), the polite way to guide a pelvis into the position I preferred. More importantly than picking up such lifetime skills, I liberated myself from doubt or shame. Sex was my true calling, my raison d’ être—as guilt-free as yoghurt, as natural as rain. Such was the self-affirming sweetness of those days that looking back, even my most brazen exploits seem choreographed by Norman Rockwell himself. There I stand, above the mantle, in adorable congress with someone picked up at the baths, and on the wall of the dining room, the kitschy tableau, “Jaz gets blown in the park.”

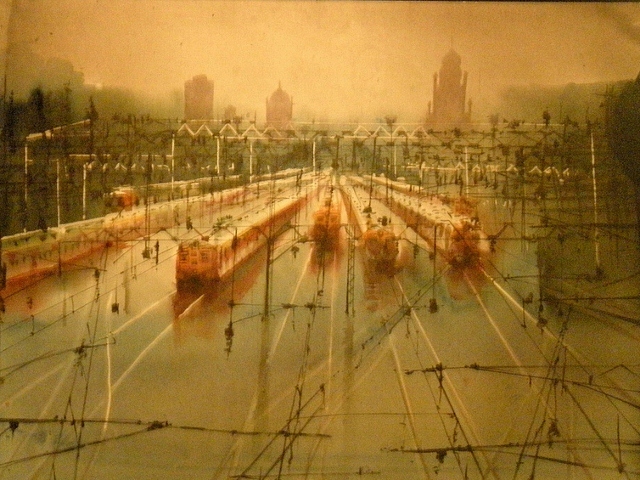

To my shock, my parents abruptly decided to return to India—to pursue the best opportunities for “true change,” they vaguely explained. What about my opportunities? I felt like screaming—the fledgling recruits at school, the network of park contacts, the sauna niche I’d carved out for myself? Back in Mumbai, though, I found more shikar than I could have ever imagined—in gardens, on streets, aboard buses and trains. My training served me well—I now knew what signs to look for, which approach to take (the trick of affecting an accent, American instead of Indian now, worked once more to give me that foreign allure). The sheer diversity of fauna amazed me—closeted bania merchants in dhotis, hotshot executives on their cell phones, migrants teeming into the city from every state. Malayalis, Gujaratis, Bengalis, even an Assamese once!—the Jazter sampled them all to create his own desi melting-pot experience.

Ah, the stories I could relate. How unfortunate the bomb’s made it too late to start a blog.

Excerpted from THE CITY OF DEVI: A NOVEL by Manil Suri. Reprinted by arrangement with WW Norton. Copyright 2013. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or printed without permission in writing from the publisher.