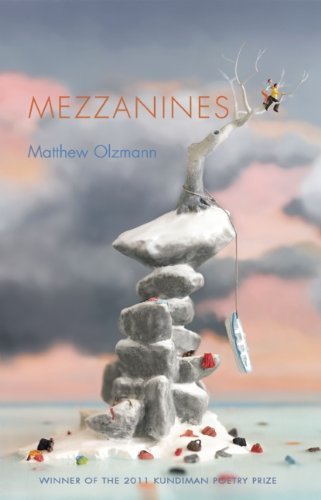

A review of Matthew Olzmann’s Mezzanines

July 11, 2014

When gazing upon shadows cast by light in a cave, Plato argues, captives name each shape and then trust in the truth of their naming. Philosophers, however, unlike captives, come to understand that reality is not comprised of shadows. The same can be said of poets. Specifically Matthew Olzmann, whose opening poem from his award-winning debut collection Mezzanines begins with a nod to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Olzmann not only names every shadowed shape in Mezzanines, he then describes them in great detail with the lights on. Such descriptions translate into an authenticity as actual as rain on a fern frond.

The poems of Mezzanines operate on poetic sense independent of reason. Olzmann is not concerned with the logic of traditional metaphor. Rather, like Spanish poet and playwright Federico Garcia Lorca, he exploits each image by means that evade rationale and induce visceral reactions. I can’t say exactly what these poems mean nor can I transcribe my response to do each justice. I can say this: the feeling I got while reading “The Tiny Men in the Horse’s Mouth” was similar to the feeling I get while listening to Erik Satie’s “Gymnopédie No.1″—indescribable, yet completely affecting.

“The Tiny Men in the Horse’s Mouth” begins with an epigraph by the comedian Dan Cummins, which questions the adage: never look a gift horse in the mouth. Cummins asks, why not? What if on the tongue of the horse in question was a miniature man playing piano? Why would one not look? How could she not? Olzmann extends this line of questioning and maintains that not looking defeats the purpose of having the gift horse, is borderline ungrateful. The real issue isn’t looking the gift horse in the mouth but, rather, the folks telling us not to. In the culminating stanzas, Olzmann writes:

Pry the jaws back

and stare through the phlegm that falls

between the teeth and the hallway of the throat.

Whoever told you not to look at this is hiding something,

Because the world is beautiful,

haunted, and begging you to receive its offering.

May you never find such music again.

Today’s poets are trained to avoid words like “beautiful” for fear of sentimentality, but I can’t think of a more fitting word to describe the world at its best and worst. As a reader, I want to feel. However, I don’t want to be told when and what to feel. Poems by poets who write against sentimentality often end up lacking sentiment altogether. Whereas sentimentality is contrived, designed to elicit a specific response at a specific time—the cued music on a television show that tells the audience when to clap or cry, sentiment is real feeling. Who wants to read poems void of all sentiment? Where’s the truth, the heart in that?

“Notes Regarding Happiness,” one of Mezzanines most expansive poems, employs language similarly. The term “happiness” is both in the title and in the last line. This move, to some, could seem tautologous, the equivalent of defining a word using the word under definition. But, considering the relativity of such an abstraction, I appreciate that the poem allows for the superimposition of the reader’s perspective. The word’s vastness lends itself to multiple interpretations, which welcomes a broader audience. Thus, widening the discussion.

Hello. I am your friend.

I am wishing you happiness.

This poem is a perfect example of how Olzmann’s mind works, and makes the most agile poet question her dexterity. The speaker first apologizes for accidentally posting gibberish birthday greetings on a friend’s facebook feed, and then launches into a three-page long harangue. In one line Olzmann refers to light and its inability to change directions. Six lines later, he takes the reader on an ill-fated flight to Brazil. Not ten lines after that, we’re underwater in a crashed plane being circled by sharks. Though the poem begins with an expression of regret and ends with well-wishes, sandwiched between are bizarre (but mostly true or plausible) examples of malfunction involving technology, institutions and Gods.

when I thought of your birthday,

I did not intend to write about

the Westboro Baptist Church, a subject

guaranteed to make birthday letters fail

the way computers fail,

the way the engines of airplanes fail,

the way Gods fail

to convince their followers to treat

each other with any level of kindness.

Olzmann prefaces the poems in Mezzanines with an epigraph from Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. It reads: We always find something…to give us the impression we exist? Love, in this collection, is one of those things. In “Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem,” the speaker catalogues reasons marriage to his partner “might” work. Because there are no guarantees in life and, therefore, none in marriage, might—not will—isn’t the most heartening word choice, but it is an honest one. While the speaker’s reasons range from the mundane to the absurd, even the mundane in an Olzmann poem is laced with absurdity.

You have soft hands. Because when we moved, the contents

of what you packed were written inside the boxes.

Because you think swans are overrated and kind of stupid.

The following last lines recall when the woman, who would become the speaker’s wife, was both cash-strapped and lovestruck. Here, reality and romance collide in a tender recollection of a precise point in time.

… And one day five summers ago,

when you couldn’t put gas in your car, when your fridge

was so empty—not even leftovers or condiments—

there was a single twenty-ounce bottle of Mountain Dew,

which you paid for with your last dime

because you once overheard me say I liked it.

Reading a book of poems is not unlike entering into a conversation. A good conversation is punctuated by moments of gravity and levity, wherein secrets are confided, wisecracks made, and trust earned. Mezzanines is a good conversation—one you’ll want to revisit and, once there, won’t want to leave. There’s an undeniable thread of truth running through the collection. From Olzmann’s opening poem, “NASA Video Transmission Picked Up by Baby Monitor,” you’ll believe him, as I believe him, because he readily admits to not knowing.

… I’ve known people, afraid

of the sun, who opened their eyes to God, but found

only a wine cellar lit by a guttering lamp. There’s so much

to be afraid of, so much to gaze at and be wrong about.

Winner of the 2011 Kundiman Poetry Prize and recipient of fellowships from the Kresge Arts Foundation and Kundiman, Matthew Olzmann is as witty as they come. His wit, however, is matched by his earnestness. This results in a poetics refreshingly out of step with the snark and detachment that characterizes much contemporary verse. As Patrick Rosal notes in his blurb, Matthew Olzmann is “amused by his own bewilderment.”