After her death, the class continued to meet every week until the end of the semester. What else could we do?

May 10, 2019

The following is part of a series of essays and reflections published on The Margins in remembrance of the life and work of poet and scholar Meena Alexander, who passed away on November 21, 2018.

The first time I went to Meena’s home for a class discussion, I was the first to arrive at her apartment. I mentioned I was a poet and she spoke about previous students who were poet-scholars. It felt good to be around a professor who understood the balancing of those two worlds, particularly since I hadn’t felt fully poet or academic in those days myself, in spite of the hours I spent reading theory and literature.

Meena’s “Writing the World” course and my “Intro to Doctoral Studies” overlapped in their exploration of the archive as institution. The first time I read Dictee, by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, was in her course and I was intrigued at the non-linear work, the combination of signage, text, and documentation in addition to the tragic death of the author. All these dimensions of documentation and history have a way of creating a power and energy imbued on the work itself.

I called her Professor for the first two months in class. It wasn’t until at her home she said, “Please, Meena.” I recall her living room covered in books and her petite body sitting carefully on her armchair, expertly insisting that we eat the food she had laid out for us, her students.

On the first day of class, she mentioned that she was drinking watermelon juice that had been specially squeezed for her by her daughter, and I thought it was a such a sensitive, loving gesture. I recall thinking that she was quite thin from the photos I had seen of her years earlier when I was first an employee at the Graduate Center (before becoming a student). I was on the elevator and there was a poster about some of the GC faculty, and there she was with fuller cheeks, lush long hair, and the sash of her sari over one shoulder. She wasn’t the type to brag or complain as a professor, which is why I didn’t learn she was sick except through an off-hand comment about her not feeling like herself after being treated at Sloan Kettering.

“Writing the World” became our own exercise in archiving, that is, digging through Meena’s syllabus. Because her health meant several absences, and leniency on deadlines and assignments, we as her students were interacting as a group with the readings and art pieces she assigned us, with and without her. In this way, we engaged with words, language, and expression in the world, placed objects and memory beside each other, listened to their conversations, learned that forming one meaning did not discredit others or prevent a multitude of further interpretations.

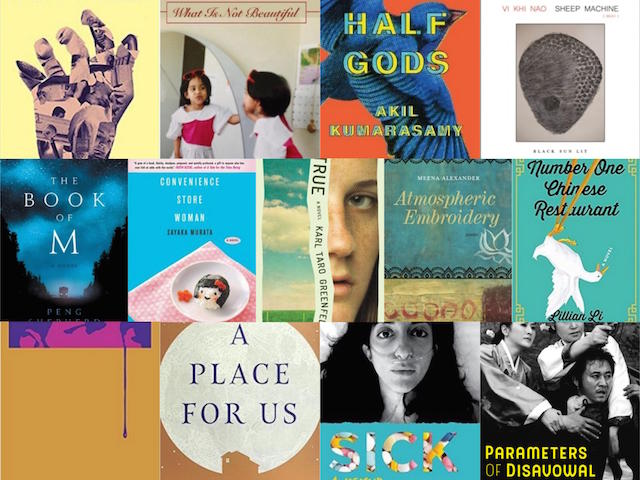

I learned that I could explore myself through literature. I saw a relationship between the trauma of Partition and South Asian writers with the legacy and growth of Khmer diaspora writers of the post-Khmer Rouge. For Khmers, it would mean an archive explored from a place of absence. I knew there was an important relationship to find and had hoped for her guidance. I thought it was a good sign when I saw that my favorite poet, Agha Shahid Ali, was included in her recent anthology, Name Me a Word.

After her death, the class continued to meet every week until the end of the semester. What else could we do? The days had to go on. Assignments, too, I guess. Some department professors graciously stepped in to evaluate our papers, but they were all men and we were a class entirely of women, mainly of color and some queer. We wanted Meena.

We learned in the beginning of the semester that we were to visit the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection as part of the class. We were told on our visit that Meena had donated her collection to their archives but they were still in storage. I wonder when it will become available to the public.

I don’t know why I’m writing this other than to record this experience. I feel she would want me to continue investigating my relationship to the archive.