Seeking a panacea from life’s turmoils, immigrants flock to an unassuming Sufi in Brooklyn.

July 26, 2018

“Who’s the last?” I murmur as I step barefoot inside the ‘magician’s’ waiting room, fully aware of the grammatically incorrect construction. I glance about, nod a greeting, and make a mental note of the young couple after whom my turn will come, before sitting on a folding chair to wait—sometimes up to an hour and a half.

Waiting: an exercise in sabr, patience. A Divine attribute.

Waiting in a room full of immigrants. Waiting in a room replete with dreams ranging from fractured to shattered, of lives gone awry, waiting at times in silence, and at others in boisterous chatter. Waiting for the arbiter of pain, for his prayerful magic to influence the lines of destiny. Every scripture in the world, it seems, possesses at least one verse on the blessings showered on those who suffer adversity in patience.

A worn faux-leather, coin-operated massage chair fills one corner of the room, gargantuan amid the folding chairs. Framed posters of Mecca and Medina adorn the wood-paneled walls. The sound of trucks and buses droning by on Coney Island Avenue and the constant shirr shirr shirr of cars being hosed down across the road at the perennially busy Giant Car Wash filter in through two slim windows.

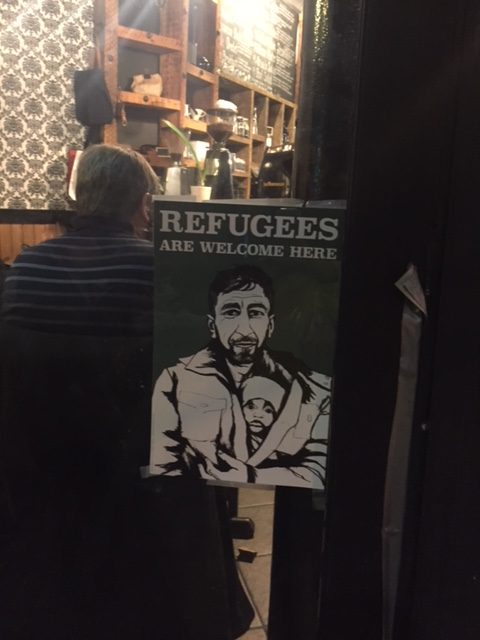

A low-income, working class neighborhood, this little stretch of Coney Island is a huddle of auto-part stores, accounting services, a shabby store-front mosque, South Asian restaurants, a grocery, a beauty salon and a travel agency. The people in the waiting room have traveled across the five boroughs and beyond to meet the magician. They have traveled from as far as Virginia and Chicago and Michigan. On any given day: Russians, Latvians, Kazakhs, Turks, Arabs, Albanians, Sikhs, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Caribbean men, women, toddlers, grandparents, teenagers form a collage of hope in a room whose walls are tacked with plastic signs and advertisements:

Please be considerate and keep the waiting area clean we also use this area to pray (sic);

Cleanliness is next to Godliness;

Al Rayaan Muslim Funeral Services;

Meeting Time 10 Mins only per family. Be considerate of others are waiting (sic)

But this is New York and even in Midwood, Brooklyn, where everyone seems to me to breathe comparatively better and easier, time is of the essence. It isn’t uncommon for someone to rush up to the shut door, shamelessly rap on it, cry out. “Ten minutes already over! Time up!”

The magician’s magic is a mystery. He speaks sotto voce and if he speaks at all it is to say “Okay, it will be okay.” He is middle aged, clean-shaven, ordinary, except for the luminosity of his gaze. He nods frequently—as if in conversation with your soul, or your aching heart, or your broken elbow. Before you’ve spoken the words that you are there to speak, he seems to know what it is that has brought you to his little room. And if you forget to mention the pain in your neck even as you list the problematic knee and the lower back spasms, he will say it himself, “And the left side of your neck, it will be okay…”

Everything will be okay. This is what we come for: his soothing presence, his confidence that everything will be okay.

***

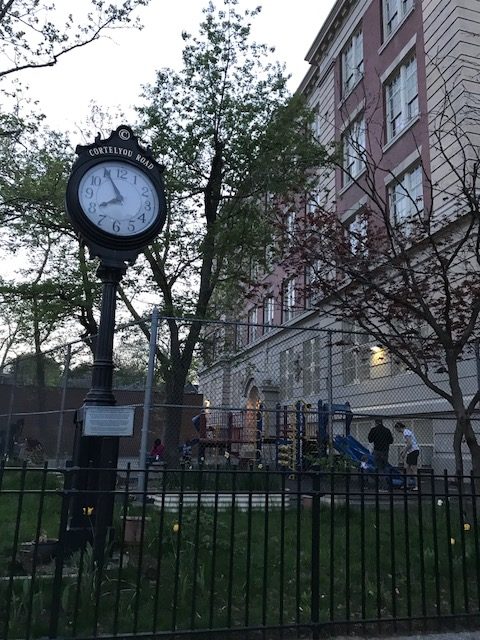

I first learned about the magician in the winter of my divorce. A light-hearted aside in a conversation after a kirtan at Broome Street Temple in SoHo led me to him. The timing was serendipitous. All avenues in my life seemed blocked and Baba Kazi, my go-to Sufi healer for existential ailments, had been away for months. I took the Q train to Cortelyou Road, and in the falling darkness, walked briskly towards Coney Island Avenue, struck by the steady gentrification of the neighborhood in the decade since I’d last roamed here. I walked right past the building, then retracing my steps discovered it sandwiched between a neon-lit Pakistani restaurant and a pharmacy. There was neither bell nor plaque to distinguish the abode. I hesitated before the dull-brown entrance, its surface a peculiar laminate, and nudged open the door.

A narrow staircase sheathed in worn carpeting snaked up to a landing. To my right a closed door. Directly across it another closed door with a pair of brown, male leather slippers parked outside. Adjacent to it, a waiting room filled with folding chairs lined up against all four walls, painted in two shades of striking orange, Urdu newspapers piled untidily on the radiator. Not a soul in sight. Where was the queue I’d been warned about? I stood outside the waiting room, wretched with sadness, unclear what to do.

“You just knock and go inside,” said a hushed voice. I turned. A young woman in a chiffon dupatta and kurta chooridaar had suddenly appeared. “But take your shoes off first.”

Two years would pass before I would have another of those rare queue-less visitations. But since that winter day, I’ve returned again and again and again. I’ve learned the local pidgin—Who’s the last? I say, stepping inside and taking a quick survey of the waiting room, my question sometimes met with a good-humored retort—You are!

As it turns out the magician is, in fact, an ordinary person. However, one could say he is a man of extraordinary faith. He sits in his little room from 8.00 a.m. to 8.00 p.m. every single day of the week, taking breaks for the two afternoon prayers and the sunset prayer, at which time he opens his door, slips on his leather sandals and climbs a flight of stairs to his private quarters on the third level of the narrow little building. He returns faithfully after 20 minutes, and the person whose turn is next rushes up from their chair and follows him into the little room.

The consultation room—what else to call it?—is pleasant and crammed with tchotchkes—vials of rose ittar, little vases, dried flowers, prayer books. A window looks out over the drab avenue and car wash. A settee with cushions lines one wall. Facing directly across it is the simple diwan on which the magician sits cross-legged in baggy shalwar kameez hour after hour. The ceiling is a painted mural of cheerful blue clouds and the wall against which his diwan rests reflects a tableau of the Kaaba surrounded by tall pilgrims framed in a bright yellow border. Once, moved by the evocative painting, I stepped outside the parameters of my troubles and asked about the artist. “The contractor,” he replied, shrugging nonchalantly. He’d given the man free reign over the room, a canvas for the aspiring artist. My mind wandered for a moment, dwelled on the immigrant contractor: whatever became of his artist dreams?

***

The magic of the magician is subtle, yet tangible. Whoever visits him, returns. Again and again, over the course of years, they return. “He’s like a prophet!” a Guyanese woman said to me once in the waiting room. She had brought three of her friends along with her and even after each of them had been inside to meet him, they returned to the waiting room to linger and chat. A woman from Long Island with a soft round face and carefully curled, blonde hair said, “I come with new problems. It works.” Dressed in a peach cashmere sweater, she exuded an enviable calm. Another said, “I drive three hours to come and see him. Troubles go away. Life straightens out.”

I’ve learned interesting tidbits in the waiting room. One day as we were waiting our turns, a woman sitting next to me, a former Estonian diplomat told me about the singing revolution of the late 80s of which she’d been a key organizer—night-singing demonstrations en masse against the Soviet occupation. A man from Kashmir said his family knew the magician’s family back in the homeland. The man’s father, an army officer, had asked the child-wonder his colleague’s names and without knowing of them or seeing them, the magician—just a little boy then—had listed the names.

“The ‘magician,’ a simple and devout Sufi armed with the power of prayer, serves as therapist and gatekeeper of our longings; his waiting room is a lesson in humility and faith, a feast of collective dreams longing to be nourished.”

Most people don’t know the magician’s name. He’s merely ‘the guy’ they go to see when a problem strikes. He doesn’t charge a fee. If a person wishes to leave a donation, they can do so discreetly, placing the notes–$1, $5, $25, $100, $500… whatever their heart dictates and their wallet allows—on a little table in the room in which he sits. Or, they can merely depart with a smile of gratitude after speaking their troubles. For his part, if he isn’t traveling overseas to his ancestral hometown or performing a pilgrimage in the holy cities, he comes downstairs from his abode each morning and takes his place on the diwan day after day, month after month, breaking only for prayer. He does not accept phone calls, but once in a rare while if the phone rings, he glances at the caller ID and selectively answers phone calls from abroad.

In the Sufi tradition, the magician is a ‘wali’—an intimate friend of God, a helper, a protector. In the waiting room, I have gleaned that he is, in fact, a lineage bearer of an ancient Sufi tradition from Kashmir, carrying the ‘torch’ given to him by his father who received it from his own. He is a man of sincere, unwavering faith, trusting completely in Divine generosity for his sustenance.

Before the magician says “Everything will be okay” and nods, he picks up a capped pen and inscribes an invisible prayer on the back of one’s palm. Sometimes he closes his eyes and gives one a message. A person might enter his room and exit after barely a minute or two. At other times, it seems they’ll never leave. Up to 30 minutes may pass before the door opens and whoever is next in line strides in with a barely concealed huff, pointing out the 10-minute courtesy rule to the person exiting.

***

A few weeks ago, on the first day of Ramadan—cool, overcast, with a fairy-like drizzle—I took the train to Midwood. As sometimes happens, I felt as though I’d slipped out of one skin of the city and into another body, this patch of otherworldly Brooklyn with its leafy trees and slow pace. Midwout, a Middle Dutch word, is the name settlers from New Netherlands gave the area, inspired by the circular patch of woods that stood centuries ago in the center of southern Brooklyn. Ancient Midwood makes me think of leys, subtle energy centers, of Jinns and Druids, ethereal beings who cluster in ancient wooded areas. I think of immigrants and their lore. I can’t help but wonder if, perhaps, the special atmosphere of the neighborhood is infused with these unseen energies.

As I approached the block, I noticed an old, old lady with a walker, leaning against the stoop of a building. Two men in kippahs were walking down a hill of rubble in an adjacent construction site and she was saying something to them. One of the men shook his head. She pulled at a bike chain threaded through the steel fence of their property. She was dressed in a white cotton shalwar kameez, bent with age. The tableau was intriguing. As I got closer, she turned her head in my direction. A muslin dupatta covered her silver hair and her white kurta was, in fact, speckled with a print of cheerful cornflowers. She beamed at me, took slow, painful steps forward, leaning on her walker, and launched into enthusiastic chatter. I couldn’t decipher her words. Then as I concentrated, her sentences started to make fragmentary sense—she was speaking in Pashto, my father’s language, a language I had not heard spoken in seventeen years. An avalanche of regret as I struggled to understand her eager monologue. Behind her plastic wide-lens spectacles, her eyes radiated an aliveness and joy at odds with her frail outer form.

“Pakhto na poaegay?”

I shook my head, no, I didn’t speak Pashto. I answered her rapid-fire questions: Yes, I have one child. That’s right, only one. God blessed me with one. A son. No, I have no husband.

In turn, she tells me she had four children, but the two younger ones are now dead. One was driving his car and was shot by a sniper. She mimics a gunman with a Kalashnikov, flexing and raising her arms as if she’s familiar with the weight and heft and length of the weapon. Then she does something alarming. Right there on the sidewalk of this orthodox stretch of Coney Island Avenue where women are meticulously veiled, she pulls down the neck of her baggy kurta, to reveal the top half of her chest. I suppress a gasp at the sunken cavity. It looks as if it has been riven and sliced in half then sewn back clumsily, forcefully. Her skin is white, with patches of bruised-blue, pleated in texture. She places her hand to her heart, closes her eyes, smiles.

Her name is Bibi Jamala. She has grandkids. She is visiting one of her children in Brooklyn—she points to the top floor of the walk-up building—but is returning to Peshawar soon. How Bibi Jamala manages to maneuver her way up the stairs to the top floor is a miracle. A greater miracle still is her joyful demeanor despite the pains in her body, the tragedies in her life.

“Why have you come here?” she asked suddenly.

It was my second visit to the magician in a week. A tension was brewing, its undercurrents dragging me down with worry: post-divorce issues, financial stress, a looming deadline.

I tell her as best I can. “Allah madad!” I said. I’ve come for prayers. There’s a holy man there, I said, pointing up the block.

Bibi Jamala looked me in the eyes, said something vibrant and uplifting in Pashto which, although I was unable to translate, made its essence known to me. Then she swung an arm around my neck, brought my head in close and kissed my hair, at once transporting me to my father’s village in north-west Pakistan, to my great grandmother, to a memory of unlettered frontier women and their vigorous embraces. Bibi Jamala muttered blessings, stood there smiling on Coney Island Avenue, a marvelous apparition from my childhood.

Such is the magic of Midwood: unseen ethereal energies intertwine with unexpected encounters, I mused, as I walked up the block to the magician’s abode, feeling lighter. For a hapless immigrant, happenstance is a waystation to hope.

***

About a week later, the simmering crisis in my life erupted. It struck with an unprecedented magnitude. It struck more forcefully than the divorce which itself had been gargantuan and destructive, ravaging health and peace of mind. Perhaps, it was the cumulative stress, the despicable nature of the betrayal, set on damaging not just me but also my child, but it took the breath out of me completely.

I rode the subway, unable to staunch the flow of sadness. If only I could harness anger, but there was only an unstoppable stream of tears. As I stepped into the ‘magician’s’ little ‘office,’ I caught in his fleeting expression a flicker of recognition. He did not look away but nodded assuredly. I sat before him in all my anguish. He was quiet as usual, but his silence lingered, as if he were listening for a message. Finally, he said, “Just wait; wait, everything will be okay.”

“Community and the intricate web of human connection that we took for granted in the old country are precious and rare as magic in the ‘new’ world.”

I climbed down the stairs, exited the building, and turning right pushed open the glass door of ‘The Guide’, the adjoining restaurant. Most of the magician’s visitors stop here for a cup of tea or a meal. It was still Ramadan. But this past week, my body churning with acute anxiety and spasms of breathlessness, I’d been unable to fast. This had been one of the hardest days, going from court building to court building, standing in endless lines, seeking answers and feeling nothing but the ache of constriction. Outside the Supreme Court Building, I’d called my mother in Canada and shamelessly allowed sobs to wrack through me in public.

Now, I ordered tea and an omelette. The server directed me to a giant rice cooker brimming with freshly cooked chicken biryani behind the serving line. I demurred.

“You must have some,” he insisted, “I’m going to give you a little on the side.”

He brought over a generous plate and set it before me. “I only work here and it’s not my place to say anything, but whatever you’re going through you must eat green chilies. It removes problems.”

“What kind of problems?” I said, the specter of hefty legal bills loomed in my mind’s eye.

“Health problems. It builds immunity. You must eat green chilies. Red chilies I can understand but green is a must, even if just a little.”

I took a bite; the biryani, vibrant with flavor, was delicious.

“I can’t tell if you’re just being polite,” he said.

“No, truly! It’s mazedar.”

The television was tuned to Urdu programming. I stared at it mindlessly as I sipped my tea, nibbled on desi omelette and biryani, savoring each bite, awash in gratitude. In the absence of family, lover, confidante, it was on this drab stretch of Coney Island Avenue that I had rediscovered a feeling of comfort—sitting before the quiet ‘magician,’ then afterwards in this modest immigrant-owned restaurant with pastel walls, receiving love piled high on a steaming plate of sumptuous biryani.

***

Philanthropy, a love of humanity, is a cardinal principle of Sufism. On any given day in Sufi shrines in the East, philanthropy as a lived practice can be evinced, most pointedly, in the ritual of langar, the distribution of free freshly cooked meals eaten communally by people of all faiths in an ethos of inclusivity. While Zakat is an obligatory charity that all able Muslims perform, Sufis have taken that injunction further—going beyond charitable support to fully embrace all human beings, regardless of their station in life, as kindred spirits. It is this embrace which renders a Sufi a philanthropist.

As it turns out, the magician would balk at the notion of magic, were I to mention it, as would his clients. Inspired prayer, purity of intention, deep compassion, trust in the unseen, faith in the Divine, the profound gift of intuition transmitted to him from his father—this is his power. Other than that, he’s just an ordinary man leading an extraordinarily disciplined life.

As I wait my turn in the waiting room, I am reminded of the words of a visiting Sufi from Ajmer, India, a direct descendant of the 12th century saint Khwajah Ghareeb Nawaz Moinuddin Chishti, also known as the Benefactor of the Poor. “Ibadah (worship) and khidmat (service) go hand in hand,” Syed Salman Chishti said. “When you visit a Sufi master or saint even the thought that comes to your heart is taken care of—you don’t need to voice it.” By being in service to life, a Sufi serves God; by embracing humanity, a Sufi serves the Divine. “The best food is the food that is shared,” he said.

The ‘magician’s’ humble abode in Midwood strikes me as a transmuted sacred space, open to all—believer, nonbeliever; sinner, saint; family, stranger—in the ancient Sufi tradition of universal love and inclusivity. Sitting in the waiting room on Coney Island Avenue, one sometimes catches glimpses of the magician’s family—wife, brother, daughter, grandchildren—as they climb the stairs to their private quarters on the third floor. Their home is open 12 hours a day, every single day of the year that he is in town, in an exemplary tradition of hospitality founded on the ideal that guests are the blessings of God.

At times, by merely climbing the stairs and sitting in the waiting room, a long sought-after peace trickles in. When one walks into his miniscule ‘office,’ one senses that even unspoken thoughts have been acknowledged. And the sharing of our life stories that inevitably happens in the waiting room offers solace and nourishment to our unsettled hearts. Conversing with people of strikingly unfamiliar backgrounds and cultures, sharing intimately of troubles amid a community of strangers is its own alchemy. In the crucible of the ‘magician’s’ waiting room, I have come to understand that misfortune and emigration, each in their own way, are equalizers of society, tearing down distinctions and barriers that would otherwise congeal us into isolate, hierarchical selves. Here, we are simply an eclectic pool of humanity, equal in our different and diverse longings.

***

One afternoon in the last week of June as I made my way towards Coney Island Avenue, I was transported to my childhood in Karachi. There was a cool breeze, an overcast sky. The air was magnetic. I could sense the sea close by, reminding me of my childhood home by the Arabian Sea. The innocence of pure, unadulterated time filled me. Bathed in this air, in sentiments of hope, I made my way to the magician. Was his presence so influential that it had the power to alter ambiance? I inhaled the sweet, penetrating fragrance of a flowering bush.

To become an immigrant—to leave home behind and set out for the unknown—is an act of blind, arguably, mad faith. It connotes trust in an unseen, unknowable future devoid of foundational certainties. Sitting in the magician’s waiting room—threshold between the seen and unseen worlds—it is fitting then that the majority of us present are immigrants, vastly different yet united in our faith in the magician and his channel to the unseen—that same unseen we took a chance on when leaving home behind. I marvel at having discovered the magician, an ambassador of the Old World, loyal to its ancient ethos. His fealty to the ways of the motherland makes my adopted country a more affable home.

In the waiting room: two Russian women, a European couple, a Pakistani mother and daughter, an Arab woman in hijab, three men who would eventually go over their allotted time by many minutes.

“What time does he come to sit?” the Pakistani lady asked no one in particular.

A man answered from across the room, “I think 8 in the morning.”

“Everyday?” She raised an eyebrow.

Philanthropy in its purest, simplest form is comprised of presence. Listening, seeing, directing compassionate attention to the one before you. A mysterious calling makes the magician come out day after day, no compulsion other than a covenant made with his father to take over. To take over, not a family ‘business,’ but rather a giving away—devoting the hours of his life to listening to other people’s heartaches and praying for relief. There is nothing rational or ‘sensible’ about what he does, sitting hour after hour on a diwan with a mural of the Kaaba behind him. He sits there not with the expectation of earning money, but simply with the wish to serve life, deeply trustful that in doing so, God will provide.

In its most essential form then, philanthropy is vital and alive in Midwood; sparkling, magical. The Sufi’s commitment to strangers, the astonishing hospitality of keeping his home open, showing up each day, giving hour after hour of his life to other people’s problems strikes me as a kind of magic. Community and the intricate web of human connection that we took for granted in the old country are precious and rare as magic in the ‘new’ world. But on Coney Island Avenue, human connectivity is rekindled as we wait in an ethos of complete trust in an economy of faith in the unseen world, a spiritual government that is active, wise and clement beyond the veil of sight.

“Like many of the immigrants in the waiting room in Midwood, I desire material security, but my longings reach farther, too, for the gold of illumination, increased knowledge, and wisdom. “

Last week, a Bangladeshi woman with dramatic eyeliner and ear pods in her ear, looked up from her phone and asked. “Does it really work? Have you come here before?” She was in a battle with her ex-husband and in-laws who were trying to take her two young daughters from her. Month after month, she’d been fighting it out in family court.

“Sometimes it works, and sometimes I don’t know. But I keep coming back about my son,” replied a Russian lady in linen shorts and t-shirt.

“Talking to him helps,” I said. “It helps me breathe.”

“Oh, yes, I know that! Sometimes it feels as if someone is breathing in for me and breathing out for me. I feel your pain.” She extricated her ear pods with an impatient brush of her hand. “We want a miracle. But, actually, it’s through people that He sends us messages. You never know who you’re going to meet.”

***

According to The Book of English Magic, magic can be usefully divided into one of two categories: high and low. “Low magic was the folk magic of the peasant or rustic whose aim is practical—to secure health, love and wealth… its purpose was not to understand the workings of the universe, but to alleviate suffering and achieve tangible, material ends.

“High magic was the pursuit of the wealthy and the aristocratic, those in power. They had access to wealth—and, supposedly, health with their expensive physicians—so their magic developed in a literate culture. It was concerned not so much with material gain as with developing the practitioner’s wisdom and understanding.”

Like many of the immigrants in the waiting room in Midwood, I desire material security, but my longings reach farther, too, for the gold of illumination, increased knowledge, and wisdom. The ‘magician,’ a simple and devout Sufi armed with the power of prayer, serves as therapist and gatekeeper of our longings; his waiting room is a lesson in humility and faith, a feast of collective dreams longing to be nourished.

Outside the waiting room, there are two plastic signs, one beige, one blue, side by side: Please don’t go in with no shoes into the waiting room (sic). But today, the waiting room is empty, his ‘office’ door ajar, brown leather sandals parked faithfully outside on the mat. I enter quietly, sit before him and shed my sadness. Wordlessly, he inscribes an invisible prayer on my right hand.

In the hallway, as I slip my shoes back on, my eyes graze the pastel orange walls, the shabby carpeting, the rickety stairs and the grammatically incorrect but declarative plastic signs; I find inordinate comfort in them. I keep staring at the signs in their clumsy English, wanting my whole self to be enfolded in these words and letters, declarative, so sure of themselves. With all the stress, perhaps I am coming unhinged, yet I have never felt clearer as I walk back out into the breeze, back to the subway station and past the flowering tree, its fragrance a benediction sending me on my hopeful way.