“Surah Rahman and Surah Yasin. Very, very powerful!”

August 3, 2012

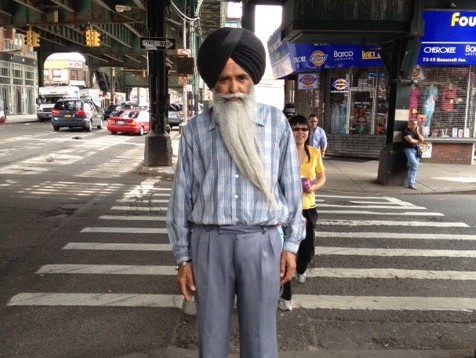

“M.D. Zuhoor-ul-Haqq is my name,” says the man in the shalwar kameez, his spine as straight as the Arabic letter alif.

“M.D.? Are you a doctor?”

“No, miss. M.D. is short for Mohammad,” he clarifies, smiling into his cheerful, henna-dyed beard.

“Oh,” I say, feeling a little foolish. Mohammad is a popular appellation for Muslim males, named in memory of the holy prophet who lived fourteen hundred years ago.

I’ve walked past Mr. Haqq’s vending stand on 74th Street in Jackson Heights more than a dozen times, tempted to chat. But on each occasion, I silently practice my opening lines and fail to deliver them, daunted by his prayer cap and upright demeanor. Now, I stand before silver rings and glass bead rosaries and an assortment of multi-hued religious souvenirs feeling as clumsy as a bull in a china shop.

“But, yes, I was village doctor for 32 years in Sirajganj District in Bangladesh,” Mr. Haqq adds, surprising me.

“Yes, yes, 32 years! I was village doctor!” he beams. His brisk fingers re-arrange the confusion of Islamic tchotchkes that are on display. His smiling eyes and neatly groomed beard render him ageless to me. A trio of customers fringes the table. Mr. Haqq bends to fetch a scarf hidden beneath the empire of Parmalat milk crates that form the foundation of his open-air stand.

As I watch a woman buy a glass paperweight in the shape of an open Quran, inscribed with a prayer, I realize that even the marginally devout will be patronizing Mr. Haqq’s stand during this holy month of Ramadan. I ask if people stop to seek his advice since he appears to be an authority on religious matters and is readily and easily accessible on the street. I’ve noticed that spirituality on the streets of Jackson Heights is as de rigueur as the neighborhood’s sumptuous ethnic cuisines. Just a few blocks away is a Navajo medicine man who rubs a coyote skin over your body and then sucks the negative energy out of you in his van, if you let him have his way. And standing just a few steps to the right of Mr. Haqq is the wife of a pandit astrologer who distributes business cards for her husband. According to the long bullet-point menu on the card, her husband can remove curses and predict the future, amongst a host of other esoteric services.

But Mr. Haqq is humble. He shakes his head, resting his hand on a pile of carved rosewood Quran holders. I repeat my question, fearing it has fallen between the gaps of our broken languages. He speaks a smattering of Hindi and English. I’ve negotiated our exchange in Urdu, English, and frantic hand motions. He picks up a slim prayer book decorated with an arabesque design. “Surah Rahman and Surah Yasin. Very, very powerful!” he exclaims. “I’m reading every day. For 24 years, every single day. Everyone should read.”

I nod in silent agreement. Distracted by the trinkets, I pick up two rings. “This one akik. Good for eye and brain problems. For $10,” he says of the agate stone set in silver. (Prophet Mohammad habitually wore an agate ring.) “And this one?” I ask of the delicate obsidian. “That one plastic. $3,” he says. His honesty is as startling as the fact that the auspicious agate shares tray space with the plastic bauble. I move on to the perfumed oils, lured by a pink box decorated with red petals. “Oh, no, that one very bad smell!” He urges me to put it back down, laughing.

I continue to marvel at the confusion of hijab scarves and packs of hijab pins, prayer mats, incense sticks, and CDs. There is a toy laptop with an Arabic keyboard and a too-loud prayer that comes on when you press a button. I chat with Mr. Haqq a little bit longer. He is observing the month of fasting, abstaining from food and water from sunrise to sunset. After he packs up his stand each night, he attends communal Ramadan prayers at the mosque on 73rd Street.

“Are women allowed there?” I ask.

“Yes,” he confirms. “Mosque is next to Bangla Plaza.”

He tells me he’s been in Jackson Heights for four months. It’s his first Ramadan in America. “Are you homesick?” I ask. He stops rearranging his display and becomes still. “No comment,” he says, with a faraway smile.

I pay $3 for a green glass-bead rosary and slip $2 into the Masjid donation box, before saying goodbye.

“Come back again, please,” Mr. Haqq says. “Journalists I like very much.