That spring my wife covered the walls of our living room in newsprint.

October 23, 2020

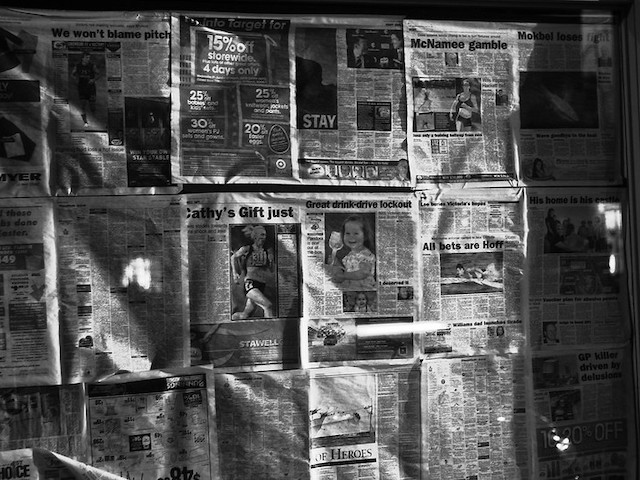

That spring my wife covered the walls of our living room in newsprint. She would draw one monster per day, she announced, and when they were on the walls they would no longer wake her up at night. For three months she dragged sticks of charcoal across the large sheets. Long, wide slashes that inked her fingertips perpetually black. After the first hour, the body was always in place. Their slack jaws resting on thick, bubbling necks. Their shining eyes and knife-like fangs. In early March we went to the doctor for my wife’s bi-annual check-up. Because you’re immunocompromised, the doctor told her, you’ll have to be doubly careful. I nodded, writing the information down in my notebook in a pantomime of calm, trying to appear in control while a low, throbbing panic began to radiate from the base of my skull. On the way home we found an old armchair on the street and hauled it up the two flights to our apartment, then felt silly for doing so. Were we crazy to have touched the chair? We let it sit for three days on the landing before dragging it into our living room and swabbing it down. Newly sanitized, it joined my office. While my wife drew I sat crunched over my laptop, telecommuting. I can make enough for the both of us, I told her. I wanted her to keep drawing. Images of the ceilings and spare rooms of my colleagues grew familiar to me, as did the interruptions of their children. I grew fond of the hum of their televisions off screen, the patches of yard I sometimes glimpsed outside of their windows. Most were too polite to ask about the monsters that hovered at the edges of my screen. I never offered explanations. What would it be like, I wondered, to live without fear? In the apartments around us we heard our neighbors moving around their spaces. Working, talking, fighting sometimes. Their music became our music. Their restlessness seeped into the walls and mingled with ours. The ash from my wife’s charcoal settled into the corners of the room. Her drawings expanded from the walls to a pile on the floor, growing like a bulwark against the enemy. We spoke to our faraway mothers and begged them to stay inside. I called the market on the corner and asked the owner if he could send one of his nephews with bags of onions, rice, and lentils. In the four years we’d lived here the grocer and I had never communicated in our common language. Brother, he said, his voice thick with regret, I have only Uncle Ben’s. At the end of each day my wife stepped back from the walls and stood with her arms at her sides, looking at what she had made. Then she walked to the bathroom and I knew not to disturb her. There she shed all of her clothes in a pile on the floor and ran a bath nearly hotter than she could stand. She soaked her tiny frame until the heat had penetrated the cords in her neck and the claw of her fists had broken open. She used an old sponge to scrub the pads of her fingertips until they were pink and new and emerged steaming from the bath, her eyes bright, wearing one of the large men’s kurtas she wore at home. This was a kind of nightly triumph. On the nights that we had exchanged a bottle of hand sanitizer for wine we climbed out on the fire escape to drink it. A toast to health, we always said, as we joined in the cheers that erupted on our street every evening at seven. On nights that we had no wine we drank milky chai. Now that her drawings covered our apartment my wife was able to sleep or wake at will, seemingly immune to caffeine. I was not so lucky. On those nights that I couldn’t stay asleep I crept back into the living room, listening to the sound of sirens. I stood in the middle of the room and dared myself to look at the monsters lit by the dim glow of the streetlight. I stared at the scales of their skin, their wet mouths hanging open to reveal the forks of their tongues. I closed my eyes and listened to their sharp keening, trying to drown out the wheezing and clicking of the ventilators, the flat lines of the monitors. Then I toasted them, taunted them, told them that they didn’t scare me even though it wasn’t true.