With mosques closing their doors, where do worshippers go to pray, be with friends, and seek solace?

March 28, 2020

Nearly hidden beneath the shadows of the elevated 7 train tracks, the Jackson Heights Islamic Center on Roosevelt Avenue appears dormant. It’s gates are half shuttered, with only a small trickle of men passing through the mosque’s discreet entrance. Within, a smaller than usual congregation, taking shelter in each other’s company, prepare to perform Isha, the final prayer of the day.

The mosque is a cramped storefront, but this evening’s service, with no more than 10 men in attendance, gives the mosque a copious feeling. Bangladeshi men sit in a semicircle, commiserating among themselves, munching on jhalmuri, a Bangladeshi version of Rice Krispies, as they await the imam to commence prayer. Despite the graciousness among the men, the air hangs heavy with a desperate sense of uncertainty. Most of the men are cab drivers.

With the outbreak of the Covid-19 bringing daily life to a standstill, eliminating any semblance of normality, the city’s taxi industry has been brought to the verge of collapse. Taxi ridership has dropped by a staggering 90 percent.

Over the past week, Nazrul Islam has been attending services daily. More so than he normally would. With yellow cab ridership down, Islam has been finding it difficult to earn a living to support his wife and three kids. Instead of driving aimlessly all day, which only causes him to lose money on gas, he has found the mosque to be an ideal place to spend his time.

“We come here to relax, to be with God and to spend time with each other,” he said. “Outside there is no work. We can’t make any money driving. It’s stressful. At least in the mosque we have some peace.”

For many of the men like Islam, the crisis has caused their livelihoods to vanish, with nearly all of them out of work for the last two weeks. Among a rapidly changing world fraught with financial insecurity, the mosque has served as a last bastion of refuge and tranquility. Yet, with the citywide ban on gatherings of more than 50 and a decline in worshippers, small mosques are unsure for how long they can hold out.

“Our number one challenge is the lack of donations,” said Imam Muhamed Sadiq, who has led the mosque for the past four years. “Now we are losing revenue (that we need to pay) for salary , for mortgage and for utilities. We need a minimum of $10,000 to survive. This month, we might only make three.”

A decline in donations is also hampering the mosque’s ambitious expansion plans that would replace a 2-story family home where it is located now with a large, traditional mosque to serve its growing congregation. Aside from a few buildings converted to mosques, Jackson Heights lacks any proper mosques. “Where do we have the money to build it?” said Imam Sadiq. “For now it’s just a dream but inshallah, it will happen soon.”

Despite the mosque’s precarious financial situation, which mirrors the financial situation of its worshippers, the mosque is still able to keep it’s door open for as long as it can. In another part of the city, that has not been the case.

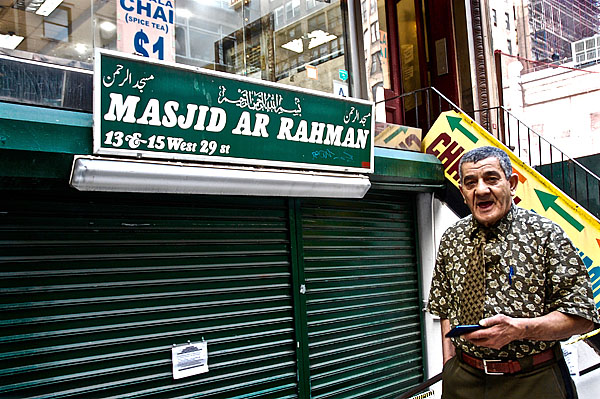

When Sammy, an Egyptian restaurant worker, headed to Masjid Ar-Rahman on West 29th street in Manhattan for Jumu’ah prayers, he was shocked to find it closed. In all of his 15 years of attendance, it was the first Friday he could remember that the mosque ever being closed. “I feel so sad. Really I do. This virus has to be as bad as they say for the mosque to close,” he said.

For Sammy, the mosque was more than a prayer space; it was also a gathering place for many immigrant men like himself, who work in the surrounding wholesale district between West 27th and 29th Streets. The rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, which is home to a menagerie of businesses selling wholesale perfume, jewelry, handbags, hair products and clothing, supports immigrant workers from Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. In many ways, the mosque was the community’s unofficial town hall.

Yet, despite Masjid Ar-Rahman being closed, men stood outside the mosque’s shuttered storefront praying and performing Duha. “Times like these, when people are nervous and out of work, they really need the mosque more than ever,” said Sammy. “The mosque gives you peace and it makes you calm. Only God knows if there will be a tomorrow.”

America is a deeply religious country. Data from the Pew Research Center shows that more than half of American adults pray on a daily basis. Yet, despite how religious we are as a country, attendance at religious services are at historic lows, with only 36 percent of Americans attend religious services regularly. As the coronavirus crisis deepens, religious institutions, already struggling with declining attendance, are finding it challenging to cope with the coronavirus crisis. Some religious institutions, such as evangelical churches, are throwing caution to the wind and outright refusing to close on the grounds of religious freedom.

Mosques around the world are facing a similar dilemma. For Muslims, the mosque is a central part of the community. Beyond just a space for prayer, a mosque is a gathering place to meet friends, cleanse the mind and perform Zakat — acts of mandatory charity required of all Muslims.

Still, heeding warnings from health experts, many mosques from Indonesia to Morocco have canceled Friday prayers, instead, encouraging Muslims to pray at home. Even the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Islam’s holiest site, was closed by the Saudi Arabian government in an effort to curb the spread of the virus.

Back at the Jackson Heights Islamic Center, Nazrul Islam is unsure were he will spend his time if the mosque closes its door. He said he is not particularly afraid of the coronavirus and hopes that things will return to normal soon. “We Muslims are not afraid because we know we can die at any time, but I understand why people become afraid. I only wish the city could make exceptions for religious places. We need the mosque more than ever.”

Imam Sadiq is more pragmatic. Intending to keep the mosque open as long as possible, Sadiq insists the mosque has taken many precautions to keep the congregation safe, such as limiting the number of people during the prayer, barring the elderly and disinfecting the building regularly.

The mosque is also preparing to create a mutual aid network to deliver food and supplies to congregants who are unable to leave their homes. Still, reluctant as he might be, Sadiq is prepared to close the mosque if forced to. “Muslims must respect the laws of this country. If the government tells us no more gatherings, we as Muslims must comply. Personally, it will be difficult but it’s our duty.”