On 30 years of living with a racist monument

July 22, 2020

In June of 1992, my then-wife and I moved to the Upper West Side and for $650 a month had secured a walk-up on a crack vial-strewn block unspooling toward the ass end of the American Museum of Natural History.

I’d known about the horse-borne sentinel policing the Museum’s entrance on the other side, of course. And I was keenly aware of the irony in finding ourselves—both organizers in leftist, Asian-American movements—new neighbors to this white supremacist colossus.

But at the time, the statue’s provocations felt soft and anemic, deriving purely from its visual lexicon of racial hierarchy: Theodore Roosevelt posed robustly in the saddle, flanked by a Native American man and an African man –half naked, on foot and in servile postures—at his stirrups.

Sure, the monument’s optics sucked. But so long as Roosevelt himself stood unindicted, its everyday pings on my consciousness were negligible, like a toddler’s jab, easily ignored.

I had not yet stumbled across accounts of Roosevelt’s slander and conduct against Black soldiers. Or his endorsement of war crimes against Filipino civilians in the Philippine-American War, and the remarkable Black-Filipino alliance that arose in response to that imperialist venture. Still unseen to me then: all the empirical texts revealing that the racist attributes were in fact baked into the subject’s character as well as his monument. And all the calamities his official acts, piloted by this white supremacist ideology, visited upon Filipinos, Black soldiers and Native Americans once he took office in 1901. These disclosures lay ahead of me.

Most crucially, my children were yet to be born, to live and play in its shadow. So in the beginning, the statue was, at worst, a mildly-disquieting presence.

And in June of 1992, there were much bigger fish to fry, it seemed. In Los Angeles, the city had only begun to clear the debris from the riots. I was in my twenties, one of the leaders of a radical Filipino-American activist youth group. Among our ranks were second gen Fil-Ams, newer immigrants like myself, bicycle messengers and Ivy League grads, high schoolers and CUNY students; and a handful of “imports,” Chinese and Korean Americans drawn to the organization’s militancy and links to the leftist, national democratic insurgency in the Philippines.

We were consumed with direct action that incendiary summer, building on a steady thrum of efforts since our founding in 1989.

We marched for Rodney King and racial justice behind Rev. Al Sharpton’s National Action Network; organized a series of workshops and protests against the renewal of the U.S. bases treaty in the Philippines; and launched an anti-police brutality campaign that nearly installed Jersey City’s first Civilian Complaint Review Board, on behalf of a well-known Filipino cartoonist named Rodin Rodriguez.

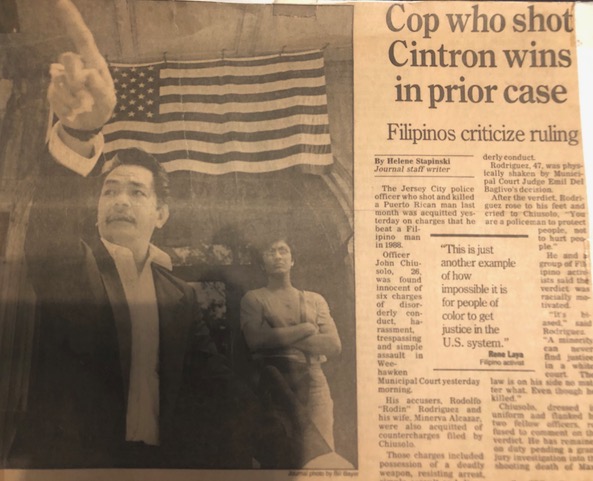

An immigrant from Manila, Rodriguez was among the pioneering cadre of Filipino comic book artists recruited to draw for US publishers Marvel and DC Comics. In 1988, after an argument over a noise complaint, Rodriguez was severely beaten in his own home and arrested by a white Jersey City police officer named John Chiusolo. Chiusolo, who had a record of excessive force complaints, handcuffed the unconscious Rodriguez behind his back, stuck his nightstick between Rodriguez’s arms and carried him to the squad car using the nightstick as a handle. An off-duty Black female corrections officer who tried to intervene was arrested for obstruction of justice. Rodriguez’s shoulders were wrenched from their sockets and the nerve damage to his wrists cost him the use of his drawing hand permanently. Chiusolo was acquitted of all charges in the subsequent civil trial.

Two years later, Chiusolo would fatally shoot Maximino “Maximo” Cintron, an unarmed truck driver of Puerto Rican descent, over a ticket for repairing his car window in the street. Cintron was only 23 years old and left behind a wife and one-year old son. Chiusolo was acquitted again after a grand jury declined to charge him. We began our campaign shortly after, going door to door in both Puerto Rican and Filipino communities that were neatly demarcated by Manila Avenue—the thoroughfare where Cintron had been slain for tinting his car windows the wrong way.

Quarreling with statuary seemed intangible and hopelessly abstract, by comparison.

And back on the Upper West Side, I was navigating an elemental force far more insistent than any damn statue: the furious churn of gentrification. The older Black and Puerto Rican families in the area had steadily receded from view. Filling the void were ripples of young white families, the scouting force for what would become a formidable stroller army.

Stepping out into the neighborhood was a daily call and response with white privilege. In Zabar’s: Call: Do you work here? Response: Look for a fucking uniform instead of profiling me. In my own building. Call: Do you live here? Response: Would you have asked me that if I looked like you? On the street (a new neighbor annoyed I’d asked him for a light): Call: Get away, Chinaman. Response: Right hook to the chin! (And a visit from the cops). It was a carousel of micro aggression. Back then, it felt like they were all Karens.

Twenty-eight years later, I write this as an era of reckoning convulses the nation. The police murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd bookending a continuum of state violence against Black and brown people, from Rodney King and Maximo Cintron that year to the present, with the stolen lives of Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, Eric Garner, and others in between.

Though I type this from within the same apartment, little of my own personal astronomy is unchanged. My wife and I had a child, a daughter now in her teens, and were separated for many years before finally divorcing. I remarried, to a Filipino-American artist originally from Los Angeles, and we have a child in kindergarten.

Like many thousands of New Yorkers, I am taking part in the street protests and vigils, though now I march as an individual.

Our youth organization imploded in 1993. It was an acrid and contentious end. Lawsuits were filed, friendships atomized. In the aftermath, I threw myself into historical research, finding sanctuary in archival collections and libraries. A magazine article I had read during my years with the group impelled me in this direction. The piece had mentioned an unnamed Black soldier who had switched sides and sacrificed his life for Philippine independence during the U.S. colonial war. Beyond the obvious allure to someone with my worldview, the soldier’s story struck me as a fish out of water saga most of all–one that resonated deeply, with my experience as a teen immigrant to New York City, and now as an organizer without a collective.

I would eventually publish essays and lecture in schools, community groups, and correctional facilities about that soldier, David Fagen from Tampa, Florida, and his audacious leap of faith in the Philippines. And it was in the course of these studies that I encountered the marrow of the Roosevelt statue.

For myself, the revelations began with a note of unintended irony from the statue’s sculptor, James Earle Fraser. Shortly after the statue’s unveiling in 1939, Fraser said the two pedestrian figures were intended as allegorical guides “symbolizing the continents of Africa and America, and if you choose may stand for Roosevelt’s friendliness to all races.”

In fact, the archives, and researchers such as Gail Lumet Buckley and Jack Foner, counter adamantly: In word and conduct, Roosevelt was friendly to only one race.

Each passage I’d read about Roosevelt seemed to alchemize the statue, from the inert visual irritant in 1992 into a pulsing heart of racial exclusion a few doors down from me.

In his May 1902 presidential remarks at Arlington National Cemetery, he justified the U.S. military’s brutal tactics against Filipinos in the Philippine-American War: Upon this “small but peculiarly trying and difficult war” turned “not only the honor of the flag,” he said, “but the triumph of civilization over forces which stand for the black chaos of savagery and barbarism.”

Four years later, in March of 1906, Roosevelt sent a telegram to Major General Leonard Wood on the island of Jolo, Mindanao: “I congratulate you and the officers and men of your command upon the brilliant feat of arms wherein you and they so well upheld the honor of the American flag.” The “brilliant feat of arms” was the March 7th massacre at a mountain called Bud Dajo, where forces under General Wood used naval gunships, machine-gun and artillery fire to kill over 1,000 mostly unarmed Muslim Filipino villagers taking refuge in a volcanic crater.

As president, he was commander-in-chief of a battalion of the African-American 25th Infantry, one of the U.S. Army’s famed “Buffalo Soldier” units. When white residents of Brownsville, Texas, accused the 25th of launching a late night “raid” which left one civilian dead, Roosevelt summarily dismissed all 167 soldiers. They forfeited all pensions and were barred from reenlistment forever, despite a mountain of exonerating evidence. Roosevelt later added that these members of the 25th were “bloody butchers” who “ought to be hung.” Investigations would reveal that the shooters used ammunition unavailable to the Black troops.

Among his first public statements as president: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are dead Indians but I believe nine out of ten are….and I wouldn’t want to inquire too closely into the case of the tenth.” One of his first official acts was to break the treaty protecting the Rosebud Sioux reservation and open up its thousands of acres to white settlement.

Am I guilty of imposing 21st century social values on an early 20th century figure? Not with this particular figure. As Andrew Ross of New York University’s American Studies program says, “When people look at certain historical figures in a revisionist light, others will say, you shouldn’t judge them by the standards of the present. But even by the standards of his own day, you could find lots of opposition to [Roosevelt’s] opinions, beliefs and policies among his own peers.”

Mark Twain wrote fiery ripostes to Roosevelt’s imperialistic harrumphs and racial ideology. As did W.E.B Du Bois and many dozens of African-American newspaper editors, who issued manifestos in solidarity with Filipino nationalists, calling them their “colored cousins” who were fighting a “race war” against an overtly racist American war of conquest.

Filipino propagandists in turn wrote recruitment appeals to Black soldiers fighting in the Philippines, beseeching them to “consider your history,” avenge “the blood of (lynching victim) Sam Hose,” and switch allegiance to their cause. David Fagen and over twenty of his peers in the U.S. Army’s segregated units heeded this call. Fagen would go on to lead hundreds of Filipino fighters in combat against the U.S. Army and become a front-page fixture in The New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle. Roosevelt personally ordered the execution of two of the Black defectors in the early 1900s.

Just as Roosevelt’s statue resonated in the national histories I read about, it has echoed the loudest in the parts of my personal narrative that involved my kids.

When my older daughter was around six or seven, we went to the Museum to visit the holiday origami tree. She bounded up the steps on Central Park West but stopped short at the statue. “Why are they naked,” she asked, pointing up at Roosevelt’s companions. I explained that “he had helped build this place and its ideas, so that’s why they put up his statue. But he was not nice to people who looked like them and us. He wrongly thought we weren’t as good as him just because we were darker skinned. Maybe that part of him came out in the statue.” She nodded quietly. It remains a searing memory. A common one, I suspect, to parents of color who have had to reconcile to their children a vision of America often at odds with immovable and near-omniscient rebuttals to that vision, like 10-foot-high monuments to racial hierarchy.

In a happy coincidence, the Museum announced on June 21 that they would be removing the statue, exactly five days after I had posted an essay on Medium beseeching for the same. “My fucking piece worked!” I joked on social media.

The weeks since the euphoria of that announcement have been an immersive experience for me, a sobering parley with the ephemeral nature of moral victories, a refresher in how swiftly our society can regress from the rare beats of enlightenment.

First came extended media interviews with Ellen Futter, the Museum’s president, wherein she “emphasized…that the decision was not about Roosevelt but about the statue itself—namely its ‘hierarchical composition.’”

To find that the well-meaning folks in power—even after all the protests and commissions—are still in the place I was 30 years ago was dispiriting. Given the historical context, to proceed in this manner is like detaining a bomb thrower for sipping an uncovered tall boy.

And on a Sunday in late June, I walked to the Museum to see if there were still the murmurs of activity I’d noticed the days before, when locals and tourists clumped together against the police barricades, snapping one last picture before the pedestal was emptied.

From a block away, I could see this was an entirely different gathering: a river of red baseball caps, and a raised cluster of U.S. flags formed a bouquet to Roosevelt on his horse. They wore seersucker suits, MAGA shirts and leather biker vests. Their signs read: “Save Teddy!” “Jews for Trump!” These were the Defenders of the Statue people. They numbered well over a hundred, and, other than all the unmasked faces, seemed organized and disciplined.

I looked across Central Park West and saw a smaller crowd of penned up counter-protestors. They had an amplifier and large speakers and a Black man was holding the microphone. I thought, “Right on, my people,” and crossed the street. They turned out to be a proselytizing Bible group, with a shrewd eye on where the crowds were going to be this sweltering Sunday afternoon.

From euphoria to uncertainty, in a heartbeat.

My younger child is now five. In early June, she wanted to ride her scooter at her favorite neighborhood spot. Ironically, that is none other than the flat and inviting expanse of marble right behind the statue. She had her head down, intent on winning a race with her Dad. So we didn’t need to have “the statue conversation” that day.

My hope was that when we do, our eyes will be resting on the statue inside the museum or elsewhere. And that her mother and I can tell her this is an exhibit about how a nation summoned the courage to reset itself, for little girls like Gianna Floyd and herself.

After the statements from Ellen Futter and observing the Defenders of the Statue gathering first hand, that outcome suddenly feels imperiled.

Perhaps our new lesson for her will be just as vital: The mission for justice is never linear, even in a time of reckoning.

It’s a push and pull across the ages, a constant state of becoming, as the old poet said. We’ll keep pushing.

(For Susan F. Quimpo, February 6, 1961 – July 14, 2020, who taught us to bear witness.)