‘Last week some of the other kids dug a hole to China in the dirt lot behind the Purtells’ house. Down at the end of Locust Street, that swampy neverland that reeked of skunk cabbage.’

September 24, 2015

The following short story by Lisa Ko is from Apogee Journal‘s fifth issue, released in May this year. Apogee’s annual benefit to raise funds for their sixth and seventh issues will be held this Friday, September 25th, 7pm, at The 8th Floor in Chelsea, NYC, with the theme of Seams—borderlines of culture, identity, and the body. Join them for drinks, refreshments, live music, a silent auction, and readings from David Mura, Jamyang Norbu, and poets Myung Mi Kim and Wo Chan to support the voices of Asian American writers and all writers we need to hear more from.

Apogee is a literary journal that combines literary aesthetic with political activism to engage with issues of identity politics and provide a platform for unheard voices, including emerging writers of color. Featuring fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and visual art, their biannual publication aims to interrogate the status quo by elevating underrepresented literary voices to affect real change across the literary and greater world.

The Night Suzy Link Goes Missing

The kids of Locust Street halt their games of Kick-the-Can and Manhunter. Inside number 33 the living room fills with red and blue light. Jocy Kwan crouches by the window, her sisters sprawled in front of the television, hair waterfalling over the couch pillows; they’re too old for kicking the can. Outside, beneath the oaks and maples, she sees the second grade kids stunned into rare silence, relenting to not only being seen with their parents, but to being protected by them, too, quietly sandwiched into their fathers’ arms.

She hears police sirens; Mrs. Link’s hiccupy crying.

The fire hydrant on the corner next to the Bradleys’ stands sentry. Out on Franklin, cars drift by, engorged by air conditioning, the rare cracked window releasing a puff of Prince, a wisp of Culture Club.

Jocy’s mother joins her at the window and whispers: Be careful.

First grade. Kids getting kidnapped, kids on milk cartons, Officer Harrison fingerprinting kids at school. Never get into a stranger’s car, Jocy’s parents warn. Bad men might want to ‘nap you. Her father tests her at dinner, making her recite her home address and phone number while her sisters snicker. They have it all memorized; she does, too.

Jocy doesn’t know why anyone would want to ‘nap her. She thinks of a black and white TV movie where a woman, tied to the train tracks by a bandit, writhes in her fluffy dress as a train approaches. Had the woman been kidnapped? The binds around her ankles and wrists strain as she twists and turns.

Jocy peed in Suzy Link’s yard once. They were digging up onion grass, clawing in the damp earth with their fingers, pulling the onions out by their long green hair and popping them into their mouths. When Jocy bit into the bulbs there was a stinging pop, the burn of onion juice in the back of her throat. I’m going to the bathroom, she said. But instead of walking to the Links’ back door, she detoured to the bushes, squatted where no one could see her and unbuttoned her overalls, pissing onto the leaves. She didn’t know why she did it; she just wanted to.

She had heard Melanie Mulligan say she saw Suzy poop in another neighbor’s yard, but Melanie also said her father had been an Olympic runner when Mr. Mulligan just won some track and field award when he was a senior at Warwick High, almost thirty years ago. There were no other, more reliable witnesses to Suzy’s alleged poop.

Nobody, to Jocy’s knowledge, had seen her peeing in the Links’ flowers—although for weeks there remained a late-night frisson of what if?

Playing with Suzy was never enjoyable. It felt like something between being alone and relieved and being alone and miserable. Nobody else wanted to play with them. Neither Jocy nor Suzy had been accepted into the world of the other kids— second graders to their first graders. The reasons for Jocy’s unacceptability were obvious, while Suzy had the right pedigree, solid Jersey roots, dark blond pigtails that actually resembled pigtails, coiled, springy, and thick. Freckled and sturdy, unlike lumpy Madge Bradley who went to Special Ed and who the boys mooed at but who still said yes when they asked her to play tag, never realizing they only wanted to see her boobs bounce. Madge’s desperation disgusted Jocy. Some kids were like that.

At the block party in June, Jocy competed with Melanie Mulligan, a pale redhead with overlapping teeth, in a game called Sponge Your Dad. A father would stand behind a picture board of a crudely drawn woman in an apron and curlers holding a rolling pin. A father would insert his face into a hole in place of the woman’s head. A child would hurl a large wet sponge at her father’s head. When it was Jocy’s turn her father had valiantly stepped in, pushing his face into the hole. But she stood at the painted line with the wet sponge in her hand and discovered she could not throw it. Her father’s face, glasses off, surrounded by painted curlers and a frilly housedress, waited for her sponge as other fathers stood on the sidelines not bothering to hide their laughter. Her father blinked at her, nearsighted and loyal. Jocy stood frozen, water dribbling down her arm, unable to hurl the sponge. Didn’t he know better? Men like Sam Kwan could not play this game. Other fathers were laughing. Other kids were staring. She wanted to pull her father out from behind the board so they could go home. Some fathers could not stand with their head in the hole and some kids could not hurl the sponge.

When it was Melanie’s turn she picked up the sponge and swung it, delivering a bulls-eye smack in the center of Mr. Mulligan’s nose. Her brothers and sisters, all four of them, cheered and clapped her on the back. You got me good, bellowed Mr. Mulligan, red-faced and barrel-chested, chuckling as the water ran down his neck.

Suzy Link had gamely tossed the sponge at Mr. Link’s face. He wiped the water off with his T-shirt. Nobody high-fived her or clapped her on the back. Jocy offered Suzy a bag of peanuts from the peanut hunt and they sat on the curb, cracking the shells and snapping them into the street.

The Kwans are outside on the front porch, a rarity at this time at night, watching the police lights on Locust Street. Up the block, a lone sprinkler is tick-tick-ticking in blatant violation of Warwick lawn watering restrictions. An open sprinkler is like free candy, but tonight nobody jumps through the umbrella spray, nobody feels the wet grass blades swipe their ankles.

No news, Jocy’s father says, shaking his head.

We need answers, Mr. Mulligan says, when the policeman tells everyone to sit tight. A child is missing! He gestures to the Links, in consultation with Officer Harrison. Mrs. Link, a squat woman in Bermuda shorts, smokes one thin cigarette after another.

Sit tight? Mr. Mulligan shouts. We need more than a few cop cars driving around. Why aren’t we calling the county? I’m of a mind to start a search team myself. Who’s with me?

The fathers of Locust Street gather in front of the Mulligans’ house, Jimmy Purtell whining when he is forbidden to join.

Jocy’s father arms himself with a flashlight and goes toward them. Her mother’s lips are twitching. Let’s go inside, she tells Jocy, and they sit at the kitchen table eating Sealtest Heavenly Hash topped with Cool Whip. Jocy’s older sisters are still in front of the TV, giggling at some shared secret.

Jocy licks Cool Whip off of a spoon as her father heads into the night with Mr. Mulligan. Had Suzy Link got into a car with a bad man? Tied up. Kidnapped. Back of the Cloverland Dairy carton, Suzy’s class picture in black and white: missing child.

Last week some of the other kids dug a hole to China in the dirt lot behind the Purtells’ house. Down at the end of Locust Street, that swampy neverland that reeked of skunk cabbage.

Jimmy Purtell had lured Jocy there once, into his treehouse, telling her Melanie Mulligan and Tasha Antonelli wanted to play with her. When Jocy scrambled up, he snatched the ladder away and danced on the patchy grass below, snorting and laughing and pulling his eyes back with his fingers, his black Doberman pacing in circles, and she had cowered in the treehouse for what seemed like hours, until he was gone and it was safe enough to jump down and run away.

The day she saw Suzy in the hole she had heard Suzy’s voice, bright and high, ringing down the block: Fine! I’ll do it!

If Suzy was there Jocy could be there, too.

Jimmy and Tasha and Melanie stood around the hole, holding plastic beach shovels caked with dirt. Jimmy had a larger shovel, made of metal, and he was poking at the dirt, loosening rocks and tossing them at trees.

We’re digging a hole to China, okay? Melanie said, as if it was obvious.

Then Jocy noticed Suzy standing inside, the top half of her body visible above the ground. Her pigtails were dotted with dirt and pebbles.

Jocy came closer but no one shooed her away. They were watching Suzy.

So are you going to do it or aren’t you? Jimmy said.

She’s chicken, Tasha said.

Suzy sniffled. I’m not chicken!

Then prove it, Melanie said. You dirty liar.

Suzy squatted, revealing polka-dot panties around her ankles. Beneath her flowered culottes, her butt was bare. She cried a little, wobbling on her feet.

That’s it, Jimmy said. You’re not allowed to go with us to China.

I can’t, Suzy said. She sniveled and whimpered, tears on her cheeks.

Told you she’s chicken, Tasha said.

And a dirty liar, said Melanie. You did it before. I saw you.

I can’t do it, she said. I can’t poop in the hole.

Now that Suzy is gone, Melanie and Tasha are the ones who are crying and Jocy’s father is in the woods with Mr. Mulligan. Never mind Suzy, Jocy wants her father to come home.

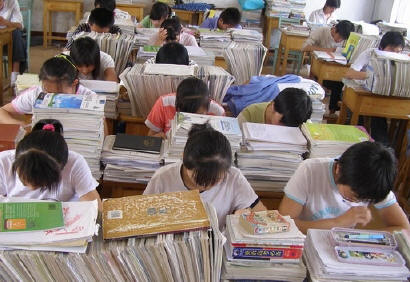

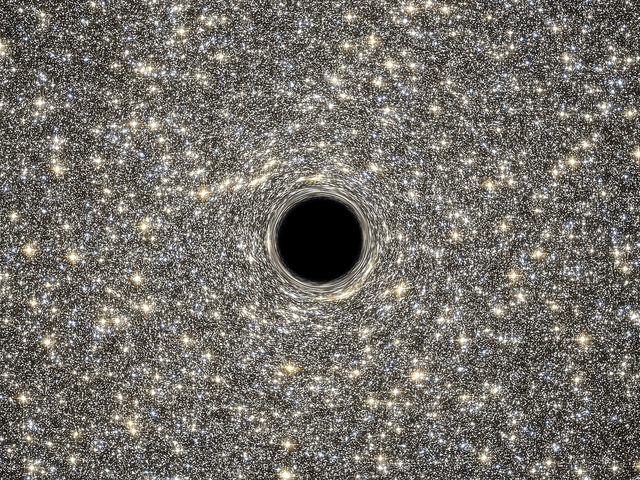

Jocy watches the shadows brush against the walls, listens to the faint laughter of the television downstairs. She wonders what a black hole feels like. Probably cold and gelatinous, a celestial custard.

The police lights are no longer outside, having moved elsewhere in search of Suzy. In the solitude of her bedroom Jocy ties her legs together with a T-shirt, blindfolds herself with a sock, and wiggles beneath her bed sheets, skin rubbing against the fabric. Her legs can part only an inch, halted by the bind. She moves her feet—halted. Scissor kicks against tightness, the T-shirt digging into her ankles—halted. It is dark beneath the sheets and blindfold, as dark as a locked closet or the trunk of a moving car.

Trapped, restrained, taken away. Helpless, tossing on the tracks, awaiting rescue. A hand waving for help in the back seat of a bad man’s car on its way out of town, driving undetected up Franklin Avenue. The hand in the window pressed flat against the glass.

The cops find Suzy at the end of Locust Street, not far from Jimmy’s treehouse and the hole to China, now abandoned and filled in with grass and branches. She was sitting alone in the skunk cabbage, looking up at the sky.

She got lost, Jocy’s mother says. She ran away.

Jocy thinks Suzy knew where she was going. Maybe Suzy had done it in the same way that Jocy peed in the Links’ yard, just wanted to, hadn’t predicted sirens and cops. Maybe she wanted to disappear.

When Jocy’s father comes home from his search team he stands in the doorway of her room as she pretends to be asleep, her eyes shut, breathing slowly. He closes the door and tiptoes away. She looks safe, but he can’t see that her legs are tied, how she is in danger.

But what bravery, or what loss, to go missing and be found only three houses from home. All those sirens and a girl can only go so far.