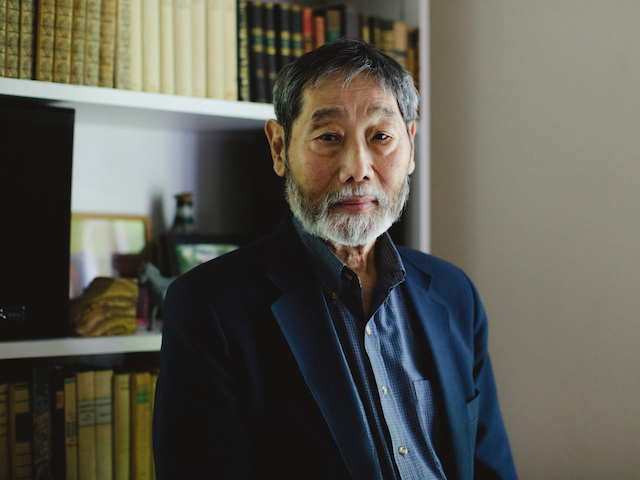

Gene Oishi, author of the novel Fox Drum Bebop, reflects on the Japanese American story beyond the wartime experience.

June 19, 2015

My grandmother, Masako “Martha” Matsuo, was born in California in 1924 to Japanese-immigrant parents. In 1942, Executive Order 9066 forcibly moved them from their home in East L.A. to the internment camp Manzanar for two years. My grandmother told me about the growing hostility at her high school leading up to her internment—the way her Chinese best friend began wearing a sticker on her blouse reading, “I am not a Jap.” She told me about the black tar smeared across the train windows to prevent the internees from ascertaining their location, and the piercing shrieks of babies throughout the cars. She told me how at age 18, when she was sponsored out of the camps to beauty school in New York City, the Caucasian girls she met wouldn’t believe she was Japanese because she was “too pretty to be a Jap!”

But when I think about my grandmother, these are not the things I think about. These stories seem to belong to another woman, another America. After the death of her husband when she was 40, and after raising six kids, four of whom were adopted, my grandmother learned how to drive, ski, swim, and scuba dive. She took trips to Central America, dove off of ships into the clear blue waters of the Caribbean, and fed barracudas Vienna sausages out of cans. At age 60, she met her current husband in the hot tub of a ski resort. A few years ago she started taking Spanish lessons, and now cautions me that the “misu” (Japanese for “water”) in the microwave is “caliente!” She dresses up as a rainbow for Halloween.

What defines my grandmother isn’t the two years she spent imprisoned, but rather the vibrant, adventurous life she cultivated for herself afterwards. The story Gene Oishi spins in Fox Drum Bebop reminds me of my grandmother’s life, not because both Hiroshi, the novel’s protagonist, and my grandmother were interned, but because they shared an enduring persistence to define their own version of Japanese and American—the reconciliation of fox drum with bebop.

With the stereotypical images of Japanese Americans that were especially prevalent during WWII, it’s easy to homogenize Japanese internment into a single narrative, and the ensuing response into a single story of struggle and success. Fox Drum Bebop suggests the opposite is true—that internment shaped the lives of internees in a myriad of ways. Each of Hiroshi’s family members responds to internment differently. One of Hiroshi’s brothers is so openly skeptical of internment that he’s sent to a special camp for particularly troublesome Japanese. Another joins the army to fight against Japan. Hiroshi’s brother Sammy is in a wheelchair, a metaphor for the political crippling of Japanese Americans. Hiroshi’s sister tries her best to just have a normal teenage existence, dancing the jitterbug and flirting with boys, while his mother compulsively hides breadcrumbs in intense fear. After these characters leave the camps, they continue to have equally diverse responses to the experience of returning to a community that allowed their unjust imprisonment, of trying to exist in a country where they are the enemy. Internment is just the beginning of Hiroshi’s story—it sets off his perpetual search for a home. It is this search, not the imprisonment that instigated it, that shapes Hiroshi’s life.

73 years after Executive Order 9066, few internees survive to tell their story. It is our job, as descendants of the interned, as descendants of those who allowed internment, or as Americans who must accept this collective history, to look back through history and hear these stories of a near-unfathomable event.

Read an excerpt from Gene Oishi’s Fox Drum Bebop in The Margins.

Mei Schultz: In your non-fiction memoir In Search of Hiroshi, you wrote that for a long time it was difficult for you to write about internment through a fictional character. What finally changed for you to able to write this book of fiction after all these years?

Gene Oishi: It was a process of maturity, understanding, and gaining self-confidence. In Search of Hiroshi started out as a novel. But strangely, I wasn’t planning to include the camp experience because I didn’t want Japanese Americans to be defined by those three years in the concentration camps. There was more to the Japanese American story than that wartime experience. But I only realized that much later. When I started In Search of Hiroshi as a novel, there was a moment when the young character’s father dies, and while the young man is grieving, he says to himself, “I am Japanese.” As I typed those words, they shocked me. I broke down in tears. And that was when I made the book a non-fiction memoir because I wasn’t able to delve very deeply into my own feelings, or into the feelings of others. So I took a very factual approach.

I had clear memories of what happened and I could rely on those memories as well as on interviews with Japanese Americans I conducted later on. I read many journalistic and scholarly accounts and decided to take the same approach, which was safer for me.

I was also working on short stories, which by definition are fiction, so I was able to sort of gradually work my way into writing a novel. Actually Fox Drum Bebop started as a collection of short stories, but I was able to turn it into a novel of linked stories, because the same characters keep showing up, especially Hiroshi, the main character who is in virtually every story.

If the Japanese American experience isn’t just confined to internment, what does it encompass, especially now, many years later?

Young people today don’t understand how racist this country used to be—how openly racist. I mean racism may still persist today, but in those days, there was nothing shameful about racism. People openly spoke about their contempt for people of other races. What made it especially difficult for Japanese Americans was being thrown in a concentration camp because you’re of Japanese race, and people saying, “A Jap is a Jap, it doesn’t matter whether you’re American or not.” As a kid I got this kind of propaganda, which was very racist and severe, while I was in the camps. I was subjected to it, but I don’t think I really believed in it. I wanted to be an American. And yet it seemed impossible to be Japanese and American at the same time. They were two contradictory states of being. I could understand it intellectually, but to accept it emotionally took some time.

Do you think writing helped you reconcile those two parts?

Well, yeah, that was really the only way. I mean, writing was a form of psychotherapy, self-psychoanalysis. It was a way of clarifying my thoughts, and it really saved me.

The family reunion scene, where Susan tries to talk to her relatives about the camps, really hit home: I’ve been that same kid, asking my family members questions but not knowing how to go about it. What should my generation understand about internment, and how do we talk to our grandparents about it?

The problem is that people who were interned are getting very old and many of them are dead. I was nine years old when I was interned. That’s the reason I wanted to write—to provide the viewpoint of someone who actually experienced internment. And, of course, the main part of the book is the aftermath. I guess today we would call it post-traumatic stress—that’s the contemporary word. But the effects still linger and will be with me for the rest of my life.

Can you talk a bit about the tension between Japanese Americans and the non-Asian ethnic minorities in the book? I’m thinking specifically about the character Ramon as well as Hiroshi, who is referred to as a Kurombo boy—the slang word for a black person.

Before the war and maybe afterward, Japanese culture was very racist, to say it bluntly. I was raised to think that being Japanese made me superior to every other race—white people, black people, brown people, even other Asians. And I don’t know how seriously I believed that. If you’re Japanese living in America you’re occupying a very subordinate position in comparison to white people, in particular. But I think it helped me, to some extent, with self-esteem.

The war and internment created doubts about my Japanese origins, my Japanese traditions. While I understood they were part of my upbringing, I felt like I had to gain some distance from my Japanese background. And I guess these characters like “Okee,” the boy from west Texas, Ramon the Mexican boy, and other people of other races were metaphors for young Hiroshi expanding his own horizons, expanding his world.

Does Hiroshi’s interest in jazz speak to that same exploration and expansion, or is it something different?

I was very attracted to jazz, but bebop was going to the cutting edge of American culture. I went to Berkeley where Bohemianism and Beatnik-ism was at its height, and that was very attractive because it was unconventional and separate from mainstream American culture, and also not Japanese, so I was killing two birds with one stone with that one.

And it’s jazz music that allows Hiroshi to go abroad to Europe.

Yeah, he’s a musician and then later on he becomes fluent in French and tries to pass as French. I was never fluent in French. Later on I became fluent in German when I was in Germany on military assignment. I found the French were much more tolerant than the Americans. They were more accepting. And I felt much more at home in France than I did in the US.

How did it feel to serve in the military for a country that had previously imprisoned you?

I joined the military not so much to join the military, but to get away. I felt suffocated by my parents, who were too worried. They wanted me to marry a nice Japanese girl and settle down and I was a very rebellious young man, as young Hiroshi was in the novel. It’s a cruel thing to say, maybe, but I wanted to be free. Once I was in the army I realized how horrible a life that would be and I was very happy when I got out. It was like getting out of prison.

Sammy, Hiroshi’s older brother, dying in the middle of the book is such a traumatic moment. Why did he have to die?

When Sammy’s alive, he’s the intellectual center of the book. He’s the only guy who understands situations clearly. He expresses himself well. So he was a very useful character. And he’s also a metaphor for political helplessness—he’s physically handicapped, stuck in this wheelchair, and I thought he was emblematic of Japanese Americans, who are, generally speaking, politically helpless. So by the end of the war—and this sounds like a heartless thing to say—he was no longer useful as a character. I didn’t know what to do with him. So I had him die. Should I bring him back to Hacienda? What would he do there? So maybe it was a bad idea, I don’t know. It would’ve been good for me as a writer if I’d faced the challenge of what to do with him, because he was interesting and helped complicate the story.

You end the book by reflecting on the concept of “home.” How did internment damage or affect your sense of home and what was the significance of ending the book with that idea?

Ever since the war started and we were shipped into camp, I felt homeless. I never felt that my hometown Guadalupe (Hacienda in the book) was my hometown after internment. And everywhere I went, I felt spiritually and emotionally homeless. Frequently, when I was very sad or very frustrated or very upset, I would say to myself, “I want to go home.” But I had no idea where that was. In the end, I realized that home is a state of mind where you feel at peace. It’s not a geographic place. Sammy was finally at home when he’s back with his parents, buried in the same block. Hiroshi always thought Sammy belonged in the desert, but, no, he belonged at home with his people.

There’s a real sense of peace at the end. Is that a reflection of how you feel about this history now?

Not quite. I’ve been back to Guadalupe a couple times. It looks exactly the same, but I didn’t have any sense of nostalgia. It’s just a place that looked familiar. That’s about it.

Over winter break I was talking to my grandmother and I was telling her about the protests that have been happening at my school in response to the grand jury decision about Michael Brown and Darren Wilson, and she just told me, “Keep your head down, don’t get involved in that, do your work.”

During the 1960s and 70s, it was only radical sansei who took part in the civil rights movement. There were few and they were radicals. Most Japanese Americans wouldn’t want to expose themselves in that way. They just felt too insecure. I believe the civil rights movement helped Asian Americans more than African Americans. It was due to the civil rights movement that I got my first job with the Associated Press, and later the Baltimore Sun, where before I would not have been able to work as a newspaper reporter.

Do you think that feeling of fear has led Japanese Americans to be a little too quiet about who they are, post internment?

Yeah. We tried to be super American, making sure we dressed properly and spoke properly as well as respectfully. We kept our lawns mowed. We were very middle class. That’s what the model minority is all about. A lot of people are uncomfortable with that designation, especially sansei, because it’s a product of fear and insecurity. We have to make ourselves models. We have to present a very friendly and safe appearance to the world around us. It used to really upset me when people would ask, “Do you know Bruce Yamamoto?” He might be living on the other side of the country, but I’m supposed to know him because he’s also Nisei. And I’d say, “Bruce, yeah, real nice guy.” That was the description of all Nisei: real nice guys. We’re all really nice guys.

I think we’re at an interesting place now historically, with so many Nisei getting old and dying. We need to be talking about internment now, when they are still alive.

But it’s hard to talk to Nisei because Nisei don’t like to talk about it. They don’t want to be reminded. My daughter is a professor of cultural studies at Claremont College and about 10 years ago she proposed a paper, a cross-generational analysis of the internment experience. It was received very well. We presented it at the Association of Asian American Studies annual meeting. I sent it to some Niseis, and one of the men was just appalled. He said, “How could you do that to your daughter? How could you bring that shame to your daughter?” And I said it was her idea, not mine. I think it’s a shame that the government did this, but it’s not a shame that should be our shame. It’s something that happened, and for many it was tragic. But there’s nothing shameful about it.

I slowly came to understand how much fear was imposed on Japanese Americans. When that man said, “How can you impose this shame on your child?” I think what he really meant was fear. You don’t really feel safe. My dream house is one made of stones with a moat around it and a draw bridge because I don’t really feel safe, even though I’ve never been threatened. I’ve led a very secure life after the war.

But this feeling of fear is very strong, and it has persisted. When my children were little, we’d go to a restaurant, and they would ask, “Do you have money? Can we pay for this?” I’d joke and say, “Oh no, I forgot my wallet! Don’t worry about it, we’ll wash dishes.” And they’d get very upset. But why would they worry about that? Somehow I had passed on a sense of insecurity to them without really knowing it. Maybe my wife had, too, because her mother was Jewish and she’d barely escaped concentration camps in Germany.

One reason why people don’t want to talk about it is because our parents were really patriotic. They wanted Japan to win the war, and that you can’t talk about, because it seems to justify what happened to us.