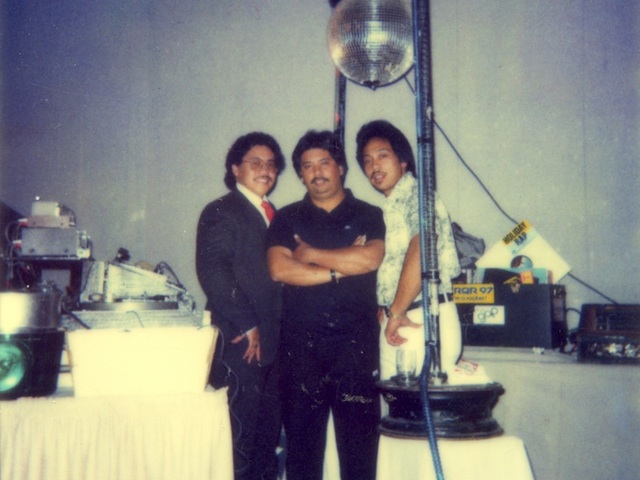

In the mid-1970s, with a DIY fog machine and light stands made of tire rims, Sound Explosion brought the experience of the discotheque back to garage parties, school dances, and weddings.

November 2, 2015

Oliver Wang’s Legions of Boom looks at the rise and reign of the Filipino American mobile DJ scene in the Bay Area. It’s a largely forgotten story animated by the ingenuity, imagination, and competitiveness of young people trying to have the most fun possible, remaking the staid garages, school gym, and church rec rooms around them with the help of massive, homemade sound systems and fog machines. Local fame proved to be an infectious lure. By the story’s end, this unassuming immigrant community will have produced some of the most innovative and globally influential DJs of the 1990s and 2000s. In this excerpt, Wang revisits the scene’s earliest years in the late 1970s, beginning with the first Filipino mobile crew: San Francisco’s Sound Explosion.

—Hua Hsu

Back in the mid-1970s, hiring a mobile disc jockey meant getting out the phonebook and flipping to the “D” section. If you were in the San Francisco area, you might end up with the Music Masters or Dr. Funk, two of the more popular phonebook DJs. They were competent at their job, possessing a decent sound system for school dances and having acceptable taste in the latest dance tunes, but as DJs, they mixed records in that old-fashioned fade-in, fade-out way. There was no nonstop mixing. There was not enough . . . flow.

For the Restauro clan at San Francisco’s Balboa High, phonebook DJs were all they originally knew. The Restauros were led by brothers Rafael and Ricky, and their core clique also included nephew Edward (who was only a couple of years younger) and honorary family member Sam Beltran. They took music seriously, especially as leaders in the school’s competitive rotc drill team, considered one of the best in the city. Drill team is all about coordinated performances set to music, so perhaps it was only natural that they would take an interest in DJs but not the staid phonebook variety. They needed something different to spark their imagination; one night in 1978, they found that at a nightclub called The Firehouse.

The clique had crossed the bay to meet up with their friend Renel Bautista at the Firehouse, a new discotheque in the city of Danville. Within minutes of stepping inside, they could tell something novel was happening. The DJs at the Firehouse were different from their phonebook variety. Instead of fading songs in and out, these DJs segued seamlessly, with each song melding into the next. This “nonstop” mixing was a revelation, a completely new way to experience music. Within days, the Restauros, Beltran, and Bautista made a decision: instead of bringing their friends out to the discotheque, they’d bring the experience of the discotheque back to their friends. Together, they formed the Bay Area’s first Filipino American–led mobile DJ crew: Sound Explosion.

The members of Sound Explosion were already used to being ahead of the curve. The Restauro family, for example, had immigrated to the United States in the late 1950s, half a decade before the Immigration Act of 1965 finally undid over forty years of draconian immigration quotas. Ricky and Rafael’s father had been a U.S. Army soldier for thirty years, and that had allowed him and other relatives to immigrate at a time when few other immigrants from Asia, let alone the Philippines, had the opportunity. In contrast to the Restauro children—all of whom were born in the United States—Sam Beltran followed a more conventional path. He was already twelve when his parents came to the United States in 1972—not coincidentally, the same year Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in the Philippines.

At Balboa, the Restauros and Beltran rose up the ranks of the school’s social hierarchy thanks to their involvement in the rotc drill team. At Balboa, the rotc rooms were where the “cool” Filipino American kids hung out, and to be on the drill team was practically like lettering in a varsity sport. Rafael Restauro eventually rose to become the drill team commander—Beltran was his xo (executive officer)—and their band of family and friends were prominent enough that the school principal would jokingly call them “the Mafia.”

After their visit to the Firehouse in the summer of 1978, Bautista and Beltran had purchased turntables and were mastering the art of nonstop mixing. By the beginning of the school year that fall, Sound Explosion were ready to make their debut. Ricky Restauro, the crew’s informal master of ceremonies and hype man, convinced Balboa’s administration to allow the crew to DJ an upcoming fall dance. This became their coming out party. “It was the first school dance of the year . . . down in the cafeteria,” Rafael recalled. “That’s when we said, ‘OK, let’s break out Sound Explosion.’ We had a little paper sign that we plastered up on a little four-by-eight plywood and had this little shiny paper on top of it.”

That first dance put Sound Explosion on the map. In their early months in 1978 and 1979, the crew did not have an organized marketing strategy, let alone access to anything akin to today’s social media advertising tools. Instead they relied on word of mouth, with each gig serving as an opportunity to audition for future clients, a process Beltran described as “reverse invitations. It wasn’t intended for us to market ourselves, but people would come up, ‘do our party, do our party.’” It helped that Sound Explosion had little competition as mobile DJs versed in nonstop mixing. “We were mixing and [audiences] were tripping out on that. They just never heard that before,” said Rafael.

Sound Explosion also brought an impressive visual flair. At that first Balboa dance, the crew spent most of their advance fee on a do-it-yourself fog machine—essentially, a fifty-gallon water tub into which they could drop dry ice. They also learned to assemble their own lighting rigs. Said Rafael, “We used to go to clubs back then and they would have all the lighting. So [we thought], ‘let’s bring our lighting here’ rather than just the cafeteria lights being turned off and flashlights and all that. We had rope lighting, we had strobe lights,” rented from theatrical supply stores.

There were no DJ specialty rental stores back then. If you could not rent the equipment you needed, you learned to build it. “Our stands for our lights and disco balls were rims of tires we put cement in. Screwed pipes in, all that stuff,” said Rafael. Their most dramatic visual props were flash pots—simple but dangerous pyrotechnic devices made from hubcaps, tissue paper, and flash powder purchased at the local magic supplies store. Because flash powder ignites on contact, the tissue acted as a makeshift fuse, but it was far from an exact science. Rafael recalled one time when he lit the fuse but it seemed to take an inordinate amount of time: “I went over there and poof, I burned all the hair off my arm.”

Sound Explosion applied the same ingenuity to their promotions. After they saved up enough money from their gigs, they purchased a van to move their heavy equipment. On weekends when they did not have a gig, they loaded their speakers—professional-grade Klipsch La Scalas— in the back of the van and connected them to their stereo. “We used to have those Klipsch, in the van, bumping off a radio. No one had a system like we had back then in a car. We had a concert in the car, it was so damn loud,” said Edward. With that mobile sound system, Rafael said, they would “run around with it and people would be drawn to [the music] and we’d give them flyers or whatever, let them know who we were.”

From a business standpoint Sound Explosion also broke new ground. Rafael registered the crew as an independent business, and by negotiating with school administrators, equipment rental stores, and venue managers, he helped to condition people to the then-unusual sight of a high school teenager handling contracts and other business agreements with adults.

Over their four-year reign, Sound Explosion were a remarkable success by any standard. As one of the few mobile crews operating in the late 1970s, they were hired throughout the Bay Area to spin at everything from garage parties to school dances to weddings. They gigged around San Francisco and neighboring cities, as far away as the Solano County Fair, forty miles from San Francisco. “Some months, we were working five weekends in a row, every Friday, every Saturday, getting $350, up to $600 every day,” recalled Rafael; this was a goodly sum not just by late 1970s standards but also for a crew of mostly sixteen- and seventeen-year-olds. Rafael added that money was not the only perk: “We used to make thousands of dollars and party at the same time. People would feed us, we’d go meet women, you know different girls from every different part [of the Bay]. . . . It was a lifestyle at the time and getting paid on top of it.”

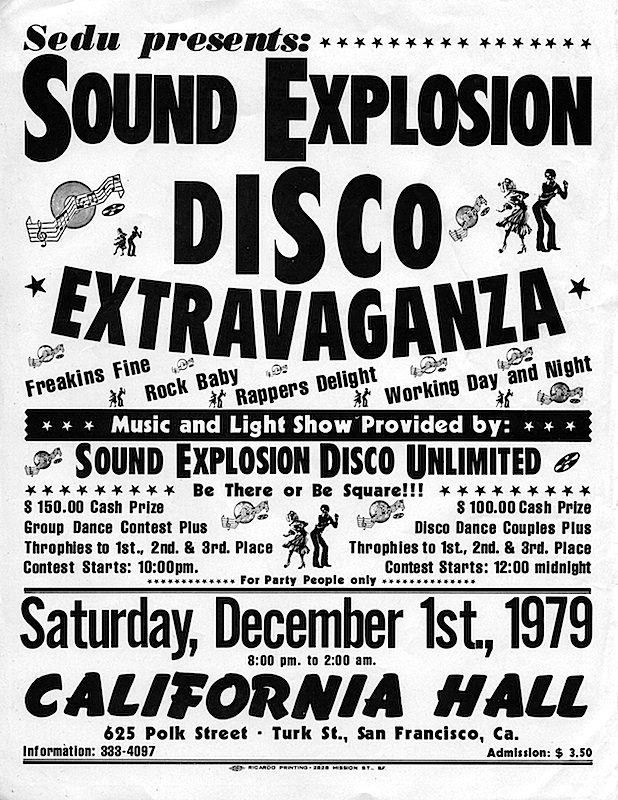

Even though the idea of starting a mobile DJ crew was unprecedented, their parents were supportive. As Rafael explained it, “they saw that we were having a lot of fun, clean fun, making money on top of it. Our parents taught us to be little entrepreneurs because, unfortunately, we didn’t have silver spoons when we were born so we had to go out and get it.” In fact, it was Rafael’s mother who helped bankroll Sound Explosion’s biggest gig, thrown on December 1, 1979, at California Hall in San Francisco.

The idea came from watching existing DJs throw similar gigs. “Dr. Funk used to have a big following and we said, ‘If he can do it, we can do it,’” Rafael explained. The crew spent six weeks promoting the event. “We used to go every weekend . . . to all the different clubs, all the way down to San Jose . . . go to the different high school dances, give out our flyers. We drew out about one thousand people at that dance,” he said. Sound Explosion also included a dance competition as part of the event, buying their own trophies for the winners and inviting dance crews from across the Bay to participate. At the event itself, the crew also struck upon a simple moneymaking strategy. Rafael recalled, “We thought about . . . OK, we’ll give them free popcorn and sell soda so we’ll get them thirsty, then we get them soda.” Edward added, “There was so much money being made there, we couldn’t even handle it. It was just all our family handling it. We didn’t really care about the money, it was all about having fun.”

In the end, though, Sound Explosion’s success generated its own discontents. In 1978, the crew had the scene practically to themselves. Within two years, their success had inspired the formation of four other mobile crews at Balboa alone, to say nothing of other nascent groups elsewhere in the Bay. These new crews might have been inspired by Sound Explosion, but they also became competitors, and Rafael complained of rampant underbidding by their new rivals. Sound Explosion’s founding members were also getting older, and what had been a teenage pursuit now felt less important as they were advancing into adulthood. Rafael recalled: “We were getting older, we had all gotten out of high school, you know. Everybody was getting into the working field . . . then the younger guys were getting all the parties at a cheaper price and we couldn’t really compete. Or, put it this way, we didn’t want to. We didn’t want to lower what we thought we were worth to what those guys were doing.” Without much formality, Sound Explosion disbanded that year, and, surprisingly, when the members left, they left completely. They stopped DJing, their records went into storage, and they never looked back. When I spoke to Rafael, Edward, and Sam about their experiences with Sound Explosion, they had little idea of how the mobile DJ scene they helped birth had eventually grown into a movement that practically defined a generation.

From Legions of Boom: Filipino American Mobile DJ Crews in the San Francisco Bay Area by Oliver Wang, published in April 2015 by Duke University Press.