Community and collaboration among Fil Am entrepreneurs

September 2, 2022

To many, the East Village is synonymous with nightlife in the city. But stop by during a weekday, and a neighborhood reveals itself differently: elderly people shade themselves on benches under London plane trees in the Allen Street Malls, an area resident rushes out of the dry cleaner with hangers of pressed shirts and slacks, and workers on their lunch break duck into one of the few open storefronts amidst the shuttered bars.

If not for the neon pennants strung from the street dining area, the small Philippine flags fluttering underneath a bright yellow awning with red letters spelling out “coffee, tea, sandwiches and sweets,” and a chalkboard propped by the open door, you might miss the entrance to Kabisera on Allen Street between Rivington and Stanton Streets.

At the most basic level, Kabisera is a café that serves up traditional Filipino and fusion fare, from bowls of arroz caldo to iced ube lattes. But in the wake of the pandemic, Kabisera has become so much more: an incubator for Filipino American small business entrepreneurs and a hub for New York City’s Fil Am community.

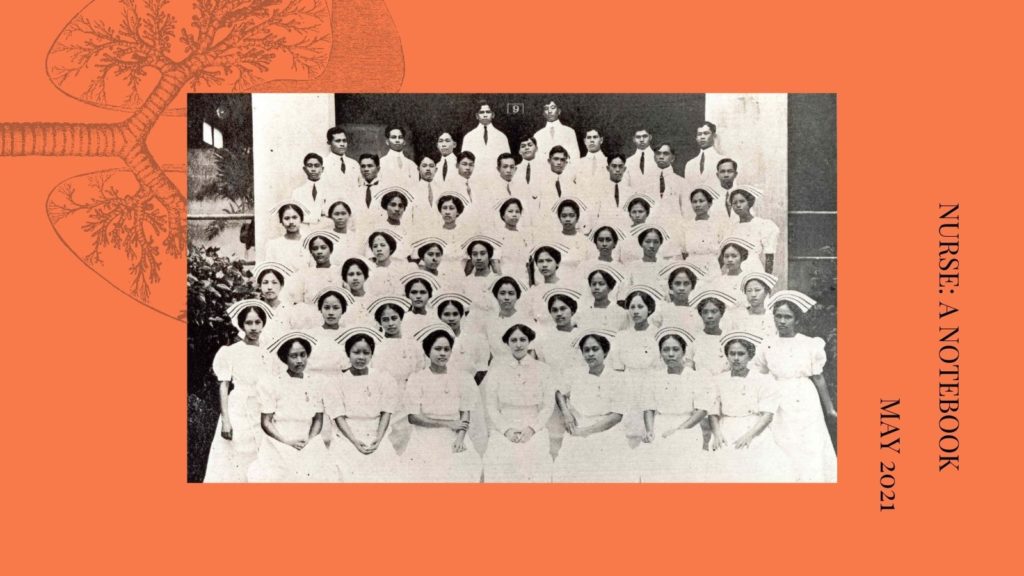

Filipino migration to New York City can be traced all the way back to early twentieth-century pensionados (Filipino students sponsored by the American colonial government as part of pacification efforts after the Philippine–American War), although the majority of Filipino immigrants arrived after the 1965 Immigration Act and have continued to do so, particularly during labor shortages such as the pandemic-induced healthcare worker shortage.

The community was hit especially hard in the beginning of the pandemic. One in four adult Filipinos in the New York–New Jersey region are employed in the healthcare field. In 2020, an estimated 31.5 percent of Covid deaths among registered nurses were Filipinos, despite the fact that only 4 percent of nurses in the United States are Filipinos.

When I arrived at the café to interview Kabisera’s chef-owner, Augelyn “Augee” Francisco, she was still busy preparing for lunch service in the open kitchen at the back of the café. A petite woman with a perennial smile, Augee exudes boundless care and energy, whether attending to the mise en place, customers in the front of house, or the community beyond Kabisera’s walls.

Augee and her partner, Joey Payumo, opened Kabisera in 2017. Augee didn’t have formal business training but felt confident that her mother—who had been chieftain of the indigenous Bago people and a shopkeeper in their hometown of Laur, Nueva Ecija, in the northern Philippines—had taught her the lessons she needed to start her own small business.

From an early age, Augee and her sister were enlisted in the family’s various businesses. As toddlers, they were fixtures behind the shop counter in their crib; as grade-schoolers, they picked and packed calamansi fruit from their farm and earned a modest cut from what was sold each day. Augee also learned to cultivate relationships in the community by watching her mother and aunt barter home-cooked meals with miners for gold that could be forged into jewelry then sold.

One lesson she drew upon during the pandemic was something her mom repeated when Augee was a child: “If you have ten friends and only one penny, your problem is dividing that penny equally among them. Because everyone who is part of your life deserves a piece of it.”

When New York went into lockdown in March 2020, Augee and Joey were among the many restaurant owners who had to assess whether it was worth staying open (given the restriction against indoor dining); the cost of ingredients like eggs, milk, butter, and flour skyrocketing threefold; and delivery fees eating away a third of the earnings.

During this time, Augee was approached by the nearby 3Stone ministry of the New York Chinese Alliance Church and the Christian & Missionary Alliance Church. They were looking to partner with the few open businesses in the neighborhood to deliver coffee and food to frontline workers in area hospitals who were working around the clock and couldn’t leave for meal breaks. Kabisera organized “coffee runs” with 3Stone. But when the ministry exhausted its funds, Augee wanted to find a way to continue the initiative. She posted a call on the restaurant’s Instagram account, inviting people to buy a coffee for a frontline worker. To her amazement, hundreds of donations came in overnight, totaling around $1,000. People not only donated funds, but those with cars also volunteered to help with deliveries.

“I think people were looking for ways to help, even if they didn’t have more than five or ten dollars to share at the time. The number of people who helped us collectively and organically, including small business owners who dropped off homemade baked goods and masks, are the ones who made it possible. Kabisera was just a tool, a connector.”

□ □ □ □ □

In April 2020, Deirdre Levy, a special education teacher at a Brooklyn public school and founder of NYC Filipinos, a platform highlighting Filipino creatives and entrepreneurs, came across the social artist Lugao Kasberg on Instagram. As a photographer and filmmaker, Lugao was compelled to document how the global pandemic was unfolding in New York, including channeling his fear and anxiety into compassion and helping the community. Deirdre reached out to Lugao and together teamed up with the organization Mask Our Heroes NYC to deliver PPE to healthcare workers. Then, through a mutual friend, they met Joey Golja, who previously worked in kitchens and wanted to deliver meals.

Deirdre, Lugao, and Joey saw the potential of empowering and organizing others to build sustainable communities of mutual aid and care. They decided to formalize their partnership and establish a nonprofit. Joey, the marketing whiz of the three, thought of the name for their new organization—Project Barkada, after the Tagalog word for a group of friends.

“The word barkada means a lot to us,” Joey explained when I met up with the cofounders at Tito Papas, a collab pop-up counter inside The Breakers bar in Williamsburg, which Joey founded in 2021 with fellow chefs Jaypee Almero and Derek Empanadas. “We’re all friends of friends . . . I’ve known VJ [Navarro] from So Sarap since 2010, then I found out Deirdre went to elementary school with him! When we all came together, it was so natural. It was like, ‘Yo, I can’t believe you’re doing this—it fits with what we’re doing too!’”

The pandemic brought to light many challenges and unmet needs in the community, but it also showed what was possible when people showed up to support one another. Project Barkada raised funds to pay for meals prepared by local chefs and businesses, including Augee of Kabisera; Jappy Afzelius of Tsismis NYC; Baker Joe’s; Joey Batista of Joey Bats Café; Joann Canosa; Derek Empanadas of Big Papas Tapas; F.O.B.; Ihawan; Joel Javier of Flip Eats; Francis Maling of Bad for Business; Pineapple in the Big Apple; Woldy Reyes of Woldy Kusina; Edie Ugo; and Harold Villarosa. A number of these businesses ended up donating meals as well. Project Barkada also recruited volunteers to deliver the meals to hospitals all over the city.

Aid efforts extended beyond New York City, as many diasporic Filipinos were equally concerned about the pandemic’s spread in the Philippines. From June to December 2020, Project Barkada enlisted volunteers in the Philippines (many of them family, friends, and friends of friends) to distribute food and PPE to healthcare workers at hospitals that were understaffed even before the pandemic, as well as to the homeless and others overlooked by government relief efforts.

Among the distribution sites were indigenous Mangyan communities in Mindoro where the maternal side of Lugao’s family is from. Through Project Barkada, Lugao was able to continue the Rice 4 Kidz program he and his mother started in 2018 to keep children in schools during the “hunger months’” that followed the devastating typhoon season.

This collective desire to help others in need can be traced to the Filipino indigenous values of kapwa and bayanihan. Kapwa, which literally means “fellow being,” is the concept that everyone is interrelated and interdependent. Bayanihan is derived from bayan, a term interchangeable for “people,” “community,” or “country.” It describes how a community comes together in the belief that kapwa have a responsibility to each other and to the world they live in. Also embedded in bayanihan is the word bayani, meaning “hero”; so bayanihan also can be translated as taking turns being a hero in the community.

□ □ □ □ □

A month into the pandemic—with the death toll surpassing 10,000, an estimated 971,800 jobs lost, and the striking absence of subway riders and street traffic—life in New York City was altered, perhaps irreversibly. Augee confided she was scared “every step of the way,” but she found strength in another of her mother’s lessons.

“Just like this virus keeps going on and on, you have to go on and on. There’s always something new happening, so we have to keep learning and relearning. Otherwise, we’re gonna get stuck; we’re gonna become obsolete.”

Through the coffee runs, Augee met Fil Ams who had lost their jobs and/or had started their own food and e-commerce businesses during the pandemic. So, in June 2020 when the city permitted restaurants to set up outdoor dining on sidewalks, Augee invited them to do pop-ups in front of Kabisera. Project Barkada built a street shed and outdoor seating to support the effort and to express gratitude to Kabisera for the community space.

Some questioned why Augee would highlight other businesses that could be considered Kabisera’s competition, which surprised her. “I never thought of it as competition. . . . When you open the door to collaboration, it actually gives you a wider horizon. You are limited if you’re alone, but if you work with more people, there will be endless open doors for you.”

Paulo Manaid, owner and designer of the clothing and accessory brand Natibo ATBP (pronounced “at iba pa,” Tagalog for “and more”), was an early donor to the coffee runs and one of the vendors Augee invited to participate in a pop-up at Kabisera. Before the pandemic, Paulo’s primary source of income was selling his signature tote bags, sweatshirts, and hats that incorporated handwoven fabrics from indigenous communities in the northern Philippines at pop-ups all over the city.

During the lockdown, he shifted to making and selling masks online to stay in business. On a video call, he recounted the dearth of places where vendors could engage with and introduce their products in person to potential customers—that is, until Augee opened Kabisera’s doors to them.

“That’s how it started, bringing in these different Fil Am–owned small businesses to uplift them,” Paulo said. “The first pop-up was a success, so we started doing it every weekend. People came to experience a little bit of the Philippines with us and at the same time helped small businesses survive.”

Paulo observed that the pop-ups drew second- and third-generation Fil Ams from beyond the New York metro area. He distinguished between first-generation Fil Ams like him who felt they had to assimilate in order to be “accepted” into American society and younger generations born and raised in the United States and who now are trying to connect with the culture their parents have suppressed.

“It’s the opposite of how we grew up—they want to be more Filipino. They want to learn about the Philippines, how life is. They’re very interested in the food and connecting to the culture by supporting our businesses. And it’s great to see a lot of awareness among young Fil Ams.”

Paulo sees Natibo ATBP as a “gateway” to the culture for his Filipino and non-Filipino customers. They usually are drawn to the bright colors and patterns of the fabric, which often are mistaken for Peruvian or Guatemalan. Most of them don’t know anything about the Philippines, let alone its handwoven fabrics.

“I remember one of the weavers I worked with in the Philippines saying that the story about the fabric is what will help me sell, and I have to say that is true. Part of my job is being an ambassador, a teacher. I tell customers about indigenous communities in Abra and other places that continue the tradition of weaving. I distinguish between the fabrics I use, which are meant to be sold to the general public, and the fabrics they weave with symbolic colors and patterns for sacred community rituals like marriages and burials.”

□ □ □ □ □

Selling and storytelling also go hand in hand for pop-up vendor MJ Yap, cofounder and co-owner of Chibundle (a portmanteau of chibog, Tagalog slang for “food” or “to eat,” and the English word bundle). On a video call, MJ explained that the idea for the specialty gift box company came about when they and their partner moved from Manila to New York City in 2017, and the only Filipino products and brands they encountered on shelves were pantry staples manufactured by large conglomerates in the Philippines.

It wasn’t surprising, given that these are brands that generations of Fil Ams recognize and seek out nostalgically but perhaps uncritically. For instance, many are unaware of the problematic labor conditions at corporations like NutriAsia, which manufactures popular condiments like banana ketchup, white cane vinegar, and soy sauce. MJ wanted to introduce the U.S. market to premium products made in the Philippines by small businesses and social enterprises focused on sustainability.

“For previous generations of Fil Ams, their perception of the Philippines might be limited to what was available back when they lived there. We’re used to making the same choices, but we can move towards better choices. I don’t just mean the products themselves but their provenance, how they’re made, what communities these products are actually impacting when you support them.”

Chibundle gift boxes feature premium food items and handcrafted goods sourced from micro- to medium-scale businesses and direct trade and social enterprises based in the Philippines, including the popular Auro Chocolate, which sources its cacao beans directly from farmers and farmer cooperatives in Davao in the southern Philippines.

For MJ, the stories are also about (and inseparable from) history, politics, and economics. Chibundle’s Mexican and Venezuelan clients, who tend to be discerning about chocolate, are often surprised that the Philippines produces fine chocolate. They are confounded even more when they learn that cacao trees in Asia have roots in Central America; that they are living legacies of the seventeenth-century Manila–Acapulco galleon trade.

Politics is personal as well for MJ. “Living in the Philippines, I’ve seen how tough it is. How the resources are few and far between. As a queer nonbinary person, it’s really hard to imagine your future in a country that doesn’t recognize you. When I moved here, I finally felt I could just focus on what I wanted to do, what I wanted to be.

“I think it’s that empathy of being undervalued, of being left out on the sidelines, that’s tied up to why I want to give a leg up to these emerging brands that deserve recognition, attention, and distribution in the U.S. I probably could make more money if I sourced super-mainstream stuff; there’s probably more demand for it as well. But that would go against the whole point of trying to create a sustainable economic impact in the Philippines.”

□ □ □ □ □

We all have experienced losses in the pandemic, not the least of which were our pre-pandemic lifestyles and mindset. But those losses also have opened us up to new experiences and opportunities. VJ Navarro was among the restaurant workers furloughed from their jobs when a number of fine-dining establishments shuttered. Without much more to lose, he and his childhood friend Sebastien Shan launched So Sarap, realizing VJ’s vision of bringing Filipino street food to New York City (no doubt influenced by his father’s experience as a street food vendor in the Philippines).

So Sarap anchored the pop-ups at Kabisera, with lines that wrapped around the block for their skewered and deep-fried fishballs, kwek kwek (quail eggs), kikiam (pork and shrimp rolls), and pork and chicken barbecue, as well as sweet fare served the traditional way—taho with sago and arnibal (silken tofu cubes and tapioca pearls drizzled with brown sugar syrup) scooped from aluminum buckets and “dirty ice cream” from sorbetes carts. But as Joey of Project Barkada pointed out, So Sarap also served as an inspiration for other creatives who wanted to start their own food pop-ups.

“I always wanted to open a restaurant. So I said, ‘Let me try to do a burger stand,’ which became Tito Boy’s Burgers. There were a lot of chefs in the community that were able to support and mentor us—VJ, Chef Harold, Chef Jappy—and now we have this,” Joey gestured at Tito Papas, a joint venture that stemmed from meeting Derek of Big Papas Tapas at the pop-ups.

What began as a handful of pop-ups evolved into Barkada Market Market, street fairs that took up stretches of Allen Street and the Allen Street Malls in June for Philippine Independence Day and in October for Filipino American History Month. Two years later, with the number of participating vendors swelling to over fifty, Barkada Market Market outgrew the location at Kabisera and moved to Greenpoint Terminal Market for this year’s Philippine Independence Day celebration.

Paulo of Natibo ATBP reflected: “If not for the pandemic, people would still be doing nine-to-five jobs. Growing up Filipino, your creative side is suppressed. I could have done this a long time ago, but I still did what my parents wanted me to do. So, I’m happy to see younger people who started with Barkada Market Market doing well. It opened up the opportunity for us to be accepted as creatives in our community.”

□ □ □ □ □

The pandemic also raised the profile of the Fil Am community in New York City. Augee was invited to contribute Filipino recipes to a new cookbook to be published by Send Chinatown Love, created in the wake of the pandemic and the surge in anti-Asian racism and violence to support struggling businesses in New York City’s Chinatown. Jane’s Walk—the annual festival organized by the Municipal Art Society of New York in honor of the writer and activist Jane Jacobs—added Kabisera to its walking tours of the Lower East Side in May. And in June, a satellite location of the restaurant opened at Canal Street Market.

In 2021, a record three Fil Ams ran for city council seats—Deirdre of Project Barkada for District 35 in Brooklyn, Marni Halasa for District 3 in Manhattan, and Steve Raga for District 26 Queens. While none won their races, Deirdre is determined to run again and is on a mission to get more elected officials to represent the Filipino community. When Steve Raga became the last-minute replacement on the ballot for District 30 in June, Deidre joined his campaign to get the votes out. Steve ended up winning the Democratic primary in District 30 in a landslide and will make history as the first Fil Am to hold statewide office in New York if he wins in the general election in November.

Meanwhile, a consequential election also took place in the Philippines in May, propelling Bongbong Marcos—son of the deposed dictator Ferdinand Marcos—to the presidency. The new vice president, Sara Duterte-Carpio, is the daughter of recent president Rodrigo Duterte, whose administration is under investigation by the International Criminal Court for extrajudicial killings and other human rights abuses in its “War on Drugs.” While Marcos Jr. implored Filipinos and the international community to “judge me not by my ancestors, but by my actions,” neither he nor Duterte-Carpio have denounced their parents’ legacies.

□ □ □ □ □

Both Paulo of Natibo ATBP and MJ of Chibundle developed relationships and workarounds that made it viable to do business with suppliers in the Philippines. They had to convince suppliers that their businesses weren’t too small to engage in the international market and supported them in applying for export licenses—an onerous process for those who don’t have influential connections in government. The pandemic further complicated the situation, and now the prospect of a new administration has added to the uncertainty.

MJ expressed their concerns: “If we take the example of the previous Marcos era, I know there were people whose businesses and lands were taken forcibly during martial law. I wonder if the same thing’s gonna happen now; how it’s gonna impact the whole local ecosystem of farming, direct trade, and small businesses. I wonder if some of these businesses even have the leverage to continue. The past Marcos administration was known for its nepotism and cronyism. If this happens again, so many people are gonna lose out.”

Yet, the Fil Am entrepreneurs I spoke with remain hopeful for the future. In spite of everything that separates the community—be it the diaspora, intergenerational clashes, a global pandemic, or politics—we have shown ourselves what’s possible through solidarity, community-building, and collaboration. We are capable of reclaiming our ancestors’ resilient practices as well as letting go of colonial ways of relating to each other, such as a scarcity or crab mentality. And by harnessing our multiplicities as Fil Ams—whether we’re first- or third-generation, indigenous or mixed-race, queer or straight, deeply connected with or only just reconnecting with the culture—we have found new, creative ways of solving problems.

“We’ve had time in the pandemic to redefine success on a personal and collective level as a community,” Lugao of Project Barkada said. “One person, a small group of people showing how to give and provide for each other is a powerful action that creates a ripple effect, and opens up new spaces for collective growth and healing.”