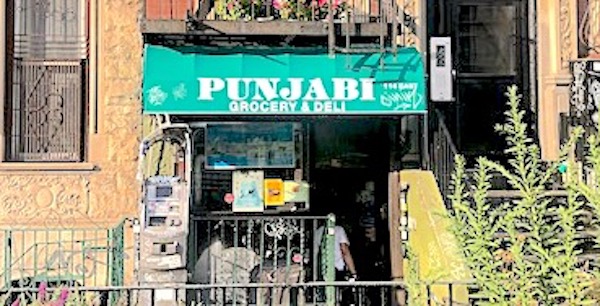

What this deli in Manhattan offers to mostly immigrant taxi drivers is priceless.

October 31, 2019

On a sunny Tuesday afternoon, a group of Sikh cab drivers mingled by the sidewalk outside Punjabi Deli and Grocery, a hole-in-the-wall tucked away by 1st Street and Avenue A in the East Village.

Two drivers, Inderjeet Singh and Gurtej Singh, have been driving cabs in New York for over 15 years. Having started a work shift at the crack of dawn, they were both on their lunch break, sipping tea and catching up on the day’s headlines in a Punjabi newspaper.

“This deli is our own people,” said Gurtej Singh, 51, in Hindi.

For the last 25 years, Punjabi Deli has offered a home away from home to thousands of cab drivers like Singh in New York City. A narrow, no-frills spot open 24 hours, seven days a week, it provides a service rarely offered to cab drivers: a free restroom.

“This place lets us use the restroom when others aren’t so accommodating,” said Gurtej Singh.

Inderjeet Singh, 38, added: “Here, you don’t have to face the discomfort of being told ‘no’.”

Kulwinder “Jani” Singh, a former yellow cab driver, opened the Deli in 1994, after he noticed the lack of accessible restrooms around the city.

“I was always told by restaurant owners, ‘we don’t have a bathroom for you’,” Singh told AAWW in Hindi. “I wanted to open this space so that if a driver wanted to buy coffee or tea, or go to the bathroom, they could.”

The lack of access to restroom facilities has contributed significantly to an alarming rate of blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) faced by taxi drivers, according to the Taxi Network, a joint research initiative between the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s Immigrant Health and Cancer Disparities Service and The South Asian Council for Social Services (SACSS).

South Asians, many hailing from countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, make up 30 percent of the 185,000 licensed drivers who are behind the wheels of New York’s yellow and green cabs and for-hire vehicles, according to 2018 data from the Taxi and Limousine Commission.

The sedentary nature of taxi driving doubles their risk of CVD, because they are more susceptible to the disease due to their ethnicity: “CVD rates in overseas Asian Indians worldwide are 50 percent to 400 percent higher than in other ethnic groups,” notes a study by the Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health.

Most drivers work 9-to-12-hour shifts, six days a week. One participant from the study said that because of cab driving, he was “unable to share time with family. Unable to take out time for his exercise. Unable to take out time for healthy food”.

Outside Punjabi Deli, drivers caught up with each other on their break and exchanged funny anecdotes about customers. They also snacked on a wide variety of Indian vegetarian food on offer, like samosa-chaat, saag paneer and sweet jalebis.

“It’s a different feeling when you eat the food from your homeland,” said Gurtej Singh. “With other food like salad, it feels like we’ve fed our stomachs but not our souls.”

“And [the deli owner] knows how to make our tea exactly the way we like it,” said Inderjeet Singh.

Shahzad Khan, 45, came to New York from Lahore, Pakistan, almost 15 years ago. In that time, he has moved from Manhattan to Long Island and changed jobs from driving a yellow cab to operating a private chauffeur service.

But even today, when he’s off his shift or visiting the city with his family on the weekends, he can’t resist making a stop at Punjabi Deli.

“There are other similar places now,” said Khan. “But I just come here, that’s all. It reminds me of my country.”

And he orders the same thing every time: “The tea. It’s the best.”

Drivers are dissuaded from taking breaks because of the low and unreliable income from taxi driving. Added to this is the difficulty of finding a parking spot, along with the fear of incurring parking tickets. “One parking ticket means day’s income is gone,” one driver told the Taxi Network.

Some reprieve may come from installing more taxi relief stands around the city to allow drivers to legally park their vehicles in public spaces. In 2015, Punjabi Deli’s owners petitioned Meera Joshi, the outgoing Commissioner of the Taxi & Limousine Commission, to have a taxi relief stand installed outside the deli. The stand is currently in operation, allowing hundreds of drivers to pull over and take breaks safely.

In Manhattan, the Department of Transportation lists 38 taxi relief stands where drivers can park their vehicles for up to an hour. In other boroughs, the number of stands is much lower, particularly in neighborhoods like Jackson Heights, Richmond Hill and Brighton Beach, which have some of the largest South Asian populations. Instead, drivers will frequent garages, religious centers, restaurants, and community centers.

But New York’s cab drivers continue to face other hardships, further adding to their health risks.

For example, the threat of harassment and concerns for personal safety are constant: “…When I switch on the radio, then every second or third day I hear the news that cabbie was killed, cabbie was assaulted, cabbie was robbed,” said another taxi driver in Urdu.

More recently, the success of ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft since 2010 has also led to cascading — and sometimes devastating — effects for the cab driving industry.

Last year, the city reckoned with a string of suicides committed by professional drivers, burdened by an unaffordable level of debt caused by the diminishing value of the taxi medallion, in the wake of app-based ride services. An executive report from an investigation led by the city’s federal prosecutors found: “[Fifty-one percent] of surveyed drivers stated they struggle to pay their monthly bills and 26 percent stated they are considering bankruptcy.

All drivers in the CVD study expressed a dissatisfaction with work, asking for legislative changes and government-mandated improvements, like reducing taxi lease fees to make costs lower and mandatory driver health insurance.

However, most still rely on community-based services for support. For example, the Taxi Network has offered free health screenings at taxi garages and community sites throughout the city, where drivers can check their blood pressure and cholesterol. It also helps drivers identify a regular doctor, and alternatives for low-cost care for important medical appointments.

The large, yet intimate community of cab drivers in New York also provides each other with support.

“We’ll often message each other on Whatsapp about any new places that open up, which serve Indian food or have a free bathroom,” said Inderjeet Singh. “We tell each other because no one else will.”

And while the local jaunts and bars around Punjabi Deli are constantly replaced with new developments, the deli hasn’t changed a single thing, offering the same comforts to thousands.

To this day, it still sports the same sign on its green-and-white awning (“I think they’ve never even painted it,” said Khan.), and continues to offer the same snacks and services. The prices haven’t staggered, either.

“It has to be reasonable so that people can afford it,” said Kulwinder ‘Jani’ Singh, the owner.

“If we change anything, there’s no sense of familiarity,” said

“Nothing has changed, including the owner’s face, even though he’s been here 20 years,” said Gurtej Singh. “I told him once, ‘Paji, I’ve satisfied my hunger with your food for years, but you haven’t changed one bit’.