Animals are strangely perceptive—in their instinct to survive, they find a home

November 22, 2017

During the so-called Malayan Emergency (1948-1960), the British colonial government displaced huge numbers of rural residents, herding them into enclosed settlements known as “new villages” to prevent them from helping the Communist guerillas. Malaysian writer and academic ZH Liew takes a sideways look at the residue left by this time of upheaval.

In 1950, you could maybe understand why they had moved here, though it was unclear if this was voluntary. We do not know if the question that should have been asked then—it went something like, Do you consent to moving to this new area, to leave behind your land?—was actually asked, or simply lost in the translation of man to records, the efficient machine, the regime of resettlement—a project with a deadline and budget. By 1952, they had become attuned to the art of creating new maps, where places like these would finally be revealed, complete, the fruits of labor by all involved. The sun began setting on this faraway tropical land—the start, when the water did not work and clothes refused to dry, now a distant memory that could be contained apart from the records.

In 1853, it was recorded that a man led a goat along this path, by all accounts an accidental story. A hundred years later, the story had entered folklore, such that when they arrived they were unable to deny its truth. No one knew where it had come from, as it was part of the fabric of life there. Not even the goat knew. But animals are strangely perceptive—in their instinct to survive, they find a home; the man could only look on, to see how these creatures had become part of his domestic landscape now.

Death and disease were common at the beginning. Famine, too, with the less than optimum land allotment and lower than usual growth of crops, the result of plans gone awry. A resettlement officer wrote in 1949, “Request for more money for land development scheme”—a vague demand for an equally vague plan read in the present as legalese, and remembered in the future as a footnote. He survives as an anonymous voice in a mass of notes, memorandums, circulars, and letters, which detail the endless strife of resource gathering and requests for assistance, for the villagers who would call this place a home.

This was what they called “the greatest development project, now being undertaken in the Federation of Malaya.” This grandiose statement recorded by observers in the 1950s now rings hollow, as is the notion that these ramshackle asbestos roofs were equivalent to the sleek, glass skyscrapers of today.

You could bring along things, goods, perhaps a trinket or two to remind yourself, the moving from place to place, the entering of a lorry’s back, the weapons that hung casually by your greeter’s side—somehow they had been given the green light to herd, to move you along like you did with your flock of animals, whom you had named according to ancient almanacs. You were fearful but also strangely excited, as if you had entered a different era with this departure. The animals knew how to return to the wild and retained a home in the distant hills. But you could not return.

In 1960, they would look back and inscribe in the records, the progress that had been made in clearing the jungle; the admirable works that were the “result of hard laboring and the capacity for self-aid and self-development”—a satisfaction in the organization, the neat division and planning which brought “many good things” in the perimeter. Shortly after, they would announce that this was a model for development, to be emulated in future places that needed to be reorganized. And it was, in fact, adopted elsewhere without them thinking too much about its consequences.

I came across these documents when I was living alone in the semi-urban space that used to be part of these villages—a half-remote place that had now become a buzzing community of industrial works, car services, ramshackle kopitiams, and even the occasional hawker with a noodle stand. The house had been on sale, and I had driven past it more than once. Its exterior was like any other house, but there were banners draped across it like a palimpsest, which now showed a generic message of “For sale. Call XXX-XXX-XXXX.”

The village didn’t seem to have properly existed until 1970; it was a late addition to the smattering of other villages that had been anointed as the future, the beginning of several important projects supposed to bring this place to maturity. Yet this house was a holdover from the past and seemed to have been there before the village was reorganized. I called without expecting the owner to pick up, but heard a voice over crackling, which told me to meet outside the house. I returned to the compound later and found the entrance unlocked, the keys hanging in the middle of the geometric door.

I had not met him before, except through a brief glance sometime ago at a photograph—his wild grin and tousled hair, atop an old metal bicycle, which seemed to have been around for more than a few years. Like the other inhabitants, he had moved in later, but he also appeared to be a writer, who had tried to integrate and learn as much of the local folklore and history as possible. Sitting at the kopitiam table, he gave the impression of a strange painting tucked away where it did not belong. Yet he had much to say about his project, as he called it, which according to him was an attempt to feel the history of a place—an original document that would encapsulate everything he had learned since he moved here five years ago. I was struck by his wild eyes that shook with conviction when he spoke; as if each sentence was a matter of life and death, the language an impossible combination of prophecy and fact. At the same time, there was also a melancholy about the way he talked about this place and himself; at one point, he suggested that he had aged unnaturally since moving here.

He kept a neatly bound notebook with a striking illustration on the cover. An animal shot through with a piercing, metal dragging the goat’s heart. A violent image, which to me fit the man’s haggard visage, his frayed eyebrows, and split hairs. Yet something about the book was attractive, if only by virtue of its age that had left tangible marks. The animal was traceable, coming to life belatedly.

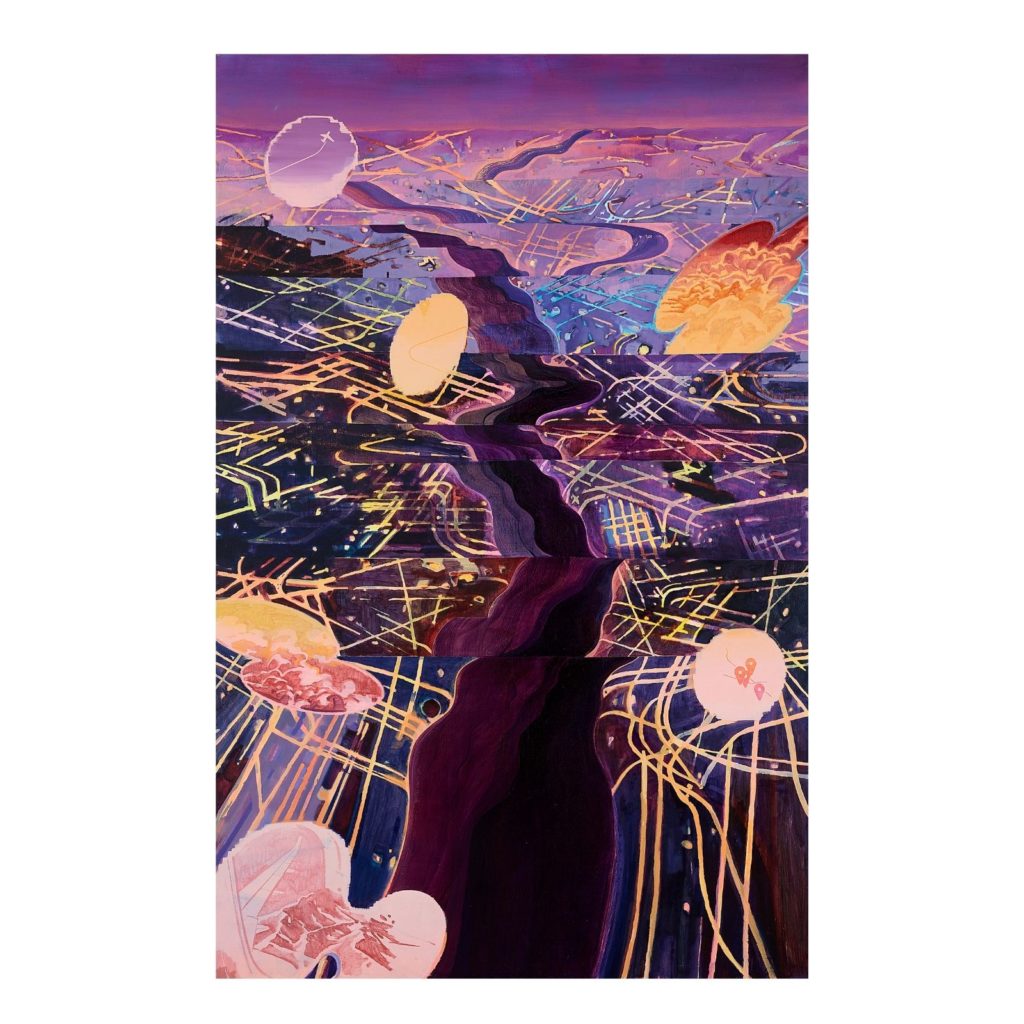

During the brief dawn that invited the day, you could see the sky colored in shades of purple and red, always a memorable scene. It was hard not to be impressed by it, the streaks of color that shone through the clouds.

Strange, then, to descend upon the bustle, a town with its usual places—except here the noisy kopitiams inhabited a sprawl of automobiles, half-dismantled tires, and curious roundabouts. Industry in its brute form—parts and pieces of objects had been torn, junk that needed to be reassembled or disintegrated. One of the workers said they had worked for hours on a car axle; from the pile of tools, I could tell most of them had arrived recently. The language was not what I had imagined—smatterings of a patois I did not recognize, through encounters with they who went about their business. The village’s construction had been mandated in a faraway office; perhaps this scene was not too different from early times, the influx of the new, a bustle of things and peoples and equipment. Yet I had not known these people as such—the yellowing papers kept in the writer’s house were not much more than letters and memorandums, circulated from office to office in administrative language.

Who could argue with the records? According to him, it was impossible to look beyond the human ingenuity that had made this a reality, even if it had generated a strange, ramshackle kind of future. The sheer audacity of starting anew—no doubt driven by primal fears of security, hunger, and the moral imposition of guns and machetes—to make a living out of things that had not necessarily been mandated (a smuggled sweet potato here, a wooden bench there) was a skill that had been cultivated with blood. During wartime, this record could have been written by anyone—an equality that stemmed from the need to survive. Herding animals would have been a necessity for the villagers; it was hard for them to argue with the language in the documents. Their very formulation was a moral threat, one that had inspired a massive clearing house, establishing something from nothing.

As far as I could tell, there was no sign of the village now. The machines—a fearful conjugation of metal and noise, resulting in billowing dust that irritated one’s lungs—had settled in the space that had been occupied by animals before. Even without this recent spate of construction, I could tell within the eyes of the villagers a sense of inevitability—the need to refashion a place in time to come, a future without a village. And that future had begun all those years ago as a note in the archive—to build and to develop the emptiness which was imagined to be without spirits, without time.

In scraps of paper I found lying in the four corners of the house, I could barely make out a story about a man and a goat. I did not know its provenance nor subject—who was the owner of this fragment, and who was he writing about? Had it been a little joke, an addendum of the mythical, now passed down as the defining word of history? It seemed to me more like a curse—one that could only be completed outside of its context, taking a life outside of itself.

I saw him again, in the interstices of the village, an alleyway tucked away without a sign, clasping a book that had yet to be written. The last time I met him he had handed me a stack of files, which had a printed logo stamped on top. Its peculiar shape reminded me of a goat—yet the animal had been transformed, transmuted with two hind legs that were mangled. Its front torso appeared to be speckled with bloodstains, a faded rusty red that encrusted the smooth fur that used to be the goat’s mane. A pair of horns protruded near the goat’s eyes, making it seem strangely human. The torturous look in its yellowing eyeballs struck me with an intensity that was impossible to forget, as if a witness to the subhuman, which could not be reconciled. He had apparently seen this image in his dreams—an animal jumping off the roof of a temporary settlement, rushing to take its own life, a movement that the villagers had tried to stop but did not comprehend.

I kept going through the yellowing files, driven by this ghost in the village. A demand from 1954 for more rubber materials—check. A need to keep the piles of rice secured, note from 1960—check. Some necessary poultry and pigs, an admission of “agricultural mistakes,” 1958—check. The files, a distinct yellow with falling bits, seemed to have been buried for a long period of time and had only been dug up by him recently. Tracing my fingers on their crumbling exterior, I discovered a note beneath the logo. Without much fanfare, it simply announced “X no longer on sale,” although it was clear someone had painstakingly dotted those words in. The red stains that bled out suggested an unusual pigment, which was eerily close to the texture of human blood.

In another possible future, the village was given a special dispensation. The war had subsided early, and the villagers had spent most of their time waiting for clearance to stay on their land, instead of being forced to enter a resettlement. Without the order to subsist in a barren land, they rediscovered the animals that had been left behind. These animals, which had names prior to their repurposing as livestock, had been roaming in exile by themselves. In their freedom, they had taken on the unsavory habits of their wild counterparts. One had started to imitate the natural tendency of goats to climb higher. It discovered that the hills were actually quite distant, but this goat remembered to snatch the leaves off hanging branches of treetops that descended halfway to the ground. Another, having decided that the villagers were not worth its time anymore, escaped to the crevices of the land and descended into a funk. Their disappearance would become the talk of the villagers, who had become used to the dependence of their animals.

This animalistic reckoning was a departure from norms that had been established for years prior to the wait—a seismic change that could only be explained by the impending shift from village to bare land. The leaving had exposed the livestock to the elements as never before; a situation only remedied by their return to a time before their housing. In that movement away, they retraced a legacy that had been fissured by their entrance into humanity. A deeper source, a wellspring of life and death that had only been hinted at prior to this curbing of their instincts. The villagers had tapped this source by sacrificing the animals before. Inexplicably, their roles were now reversed.

The Malay hikayats record this movement as natural—the result of certain necessary occurrences, otherwise known as fate, a confrontation with nature through death. Rituals hold the moment of departure; myths describe animals as indispensable. To safely depart the world, animals led the way as they would reach the afterlife in due course, the calm leaving in contrast with the stormy event of death. But this story itself was an invention to rationalize departures that had not been understood—a painful and irrevocable journey made plausible, to folk in other places.

Perhaps he had never left the village. Under the dusking sky, I drove past this urban setting, many years after I had lost the files I’d found. Sitting at an unassuming stall next to the road, I saw a man with a book in his hand, carrying a goat towards the hills.