Pulled up in the net of memory

This piece is part of the 随筆 | Zuihitsu notebook, which features original art by Satsuki Shibuya.

I didn’t know what kind of orchid plant was in the pot near my front door. It had a pseudobulb, so in case the plant was still alive, I watered it a little a few times a week. Months later, two leaves sprouted and grew into thick leaves. Then something emerged from the base of a leaf. A curled bright pink inflorescence started to push itself out of its sheath. When the orchid bloomed, I saw it was a cattleya. The pedicel was bent, so the flower bowed its lovely face down toward the ground. Should I stake it to hold the flower up? I let it be.

The color orchid is not just purple. It is the color of cattleya orchids.

My father’s father raised orchids. My mother’s father built houses and buildings.

Clutter of memories

Not puzzle pieces that fit

Just fragments, impressions,

Shape and shadow

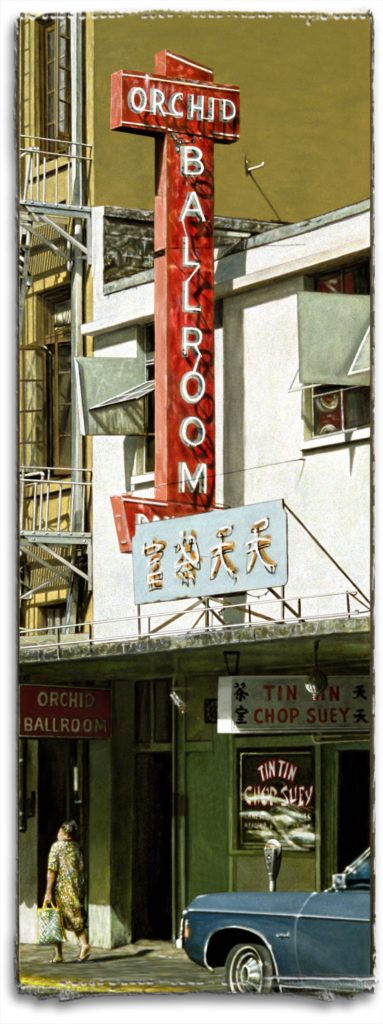

My memory of 1970s Chinatown at night includes the Orchid Ballroom neon sign glowing the vivid color of the frilled lip of a cattleya orchid above Tin Tin Chop Suey. But who can rely on memory?

I asked some friends if they remembered the Orchid Ballroom sign on Maunakea Street, but none of them did or even knew there were still taxi dance halls in the seventies. They all remembered eating at Tin Tin Chop Suey.

Back then I knew the Orchid Ballroom was a taxi dance hall, and I was curious about it. I didn’t think it was dangerous, but it didn’t feel quite right to go there alone at night, and I would have felt like an outsider. I wish I had walked up those stairs. My friend mentioned my question about the Orchid Ballroom sign to her husband, and though he didn’t remember the sign, he and his best friend went there a couple times in the seventies for the live music—the band played kachi kachi and love songs. And the best friend danced a couple songs with a girl. Some of the girls were college students. Most of the customers were old Filipino men. It wasn’t very crowded.

In postwar Honolulu, soldiers and sailors also patronized the taxi dance halls. A ticket bought a minute or two of dancing, and the band might play nonstop, changing tempo and starting a new song to mark the dance time bought by a ticket. Some dance halls would ring a bell to mark the dance time. A whole song could be 3 or 4 bells long. When the band started a new song or the bell rang to mark the end of the dance time bought by a ticket, the man had to give the dance hostess another ticket to continue dancing with her.

My friend’s husband doesn’t remember a bell at the Orchid Ballroom when he went there in the seventies.

Taxi dancers could do ballroom dancing, including foxtrot and cha-cha.

We were required to learn how to box-step foxtrot and cha-cha in PE class in seventh or eighth grade. It was called “social dancing.” Box-step foxtrot: one-two-three-four, one-two-three-four. Cha-cha: one-two, cha-cha-cha; one-two, cha-cha-cha.

In the early seventies, plans for Chinatown redevelopment identified some old buildings not designated as historic for demolition to make way for new buildings. Old-time businesses and residents would be displaced. Where could they go? Activists, business owners, residents, government officials, developers, and politicians got embroiled in protests, meetings, hearings. People Against Chinatown Evictions pushed for affordable housing for residents who wanted to continue living in Chinatown. Third Arm ran a free medical clinic on Pauahi Street.

Names float,

Surface after such a long time,

Pulled up in the net of memory.

The Palace Ballroom, Tin Tin Chop Suey, and the Orchid Ballroom were in one of the buildings slated for redevelopment demolition.

The Palace Ballroom was the oldest taxi dance hall in Chinatown.

Tin Tin Chop Suey was popular with downtown workers for lunch and was the Chinese restaurant to go to after midnight.

In a 1965 Honolulu Star-Bulletin classified ad, the Orchid Ballroom claimed to be the “busiest ballroom in town.” Dance hostesses could gross up to $250 for thirty hours a week, and transportation was offered.

In the seventies, a dance ticket was fifty cents (twenty-five cents went to the dance hostess). Coffee with a girl might be a minimum five dollars plus the cost of the coffee.

In the seventies, the Orchid Ballroom was used for workshops and public meetings about Chinatown redevelopment, including an all-day conference in summer 1977.

I don’t know when the Orchid Ballroom closed.

Tin Tin Chop Suey closed its doors for the last time at 3 a.m. in February 1985.

The Palace Ballroom closed in late 1984. It was a place for the regulars to see their friends and maybe dance. The last night at the Palace Ballroom was not crowded. The few regulars—mostly old Filipino men. The few remaining dancers. The band. The last song.

But the Palace Ballroom wasn’t the last taxi dance hall in Chinatown; Benny’s Dance Land on Hotel Street was. It was open 7 p.m. to midnight. According to a 1996 Honolulu Advertiser classified ad for Benny’s Dance Land, dancers could earn $85 to $100 a night commission. By the 1990s, a dance ticket cost five dollars for five minutes instead of fifty cents for a minute. Most of the dancers were college students or military wives. Benny’s Dance Hall included a restaurant where the owner cooked Filipino food, and the customers could hang out and talk story. There was a pool table, too. Eventually the dance hall had to switch from live bands to music tapes because the musicians got too old or passed away. But some of the customers, mostly old Filipino men, still danced. It was somewhere to have fun, relax, and see friends. No fights or trouble. Benny’s Dance Hall closed in 1999.

Time and place

memories woven

stories lost and found

Who remembers People Against Chinatown Eviction? Who remembers Third Arm? Who remembers the Aloha Hotel protest? Who remembers who lived at Pauahi Hale and stayed after it was renovated? Who remembers the old buildings being razed and new structures rising in their places? Who remembers who got keys to affordable units in the Smith-Beretania Apartments? Who remembers the residents-turned-activists? Who remembers Chinatown of that time? Who is watching Chinatown now?

Since the seventies, there have been three tiger years—1986, 1998, and 2010. This year, 2022, is the year of the tiger. The tiger’s roar is so powerful it paralyzes other animals, but it’s not what people can hear that paralyzes. It’s what we might feel but cannot hear—low frequency infrasounds passing through us.

I drive through Chinatown looking at people, buildings, signs. People are celebrating Chinese New Year, and Maunakea Street is busy. There’s a long line of people waiting outside Sing Cheong Yuan Bakery, probably to buy gau and New Year good-luck candied vegetables and fruits—lotus root, winter squash, kumquat, coconut. Everyone is wearing masks in this time of Covid.

A young rooster appeared in my front yard last week. He had glossy black feathers. He was sleek and slim like teenagers can be, curious and unafraid. Quick. When he crossed the street, he had the good sense to run like crazy before any car could hit him.

A new cat has appeared in the neighborhood. It is the color of smoke and never crosses to my side of the street. I don’t know where it goes.

My friend’s daughter’s dog has idiopathic old dog disease.

The cattleya orchid plant has one flower, six leaves, and two more pseudobulbs.

About the Art: “Tin Tin, Orchid Ballroom” is one of artist Doug Young’s twenty-plus images of buildings in Honolulu’s Chinatown. Young made the series in the 1970s. He writes, “There was a movement to revamp Chinatown and evict the residents. The ethnic studies department from the University of Hawaiʻi was doing protest marches, and I thought of documenting/preserving these old store fronts.”